Congress punts on student loan interest rates

- Share via

Congress racked up another F this week, failing to stop a looming increase in student loan interest rates that both parties say they oppose. Friday will be the last day for college students of modest means to obtain a federal loan at the ultra-low interest rate of 3.4%, at least for a while. The rate jumps to 6.8% Monday for new subsidized Stafford loans, a type of loan available only to students from low- and moderate-income families.

Lawmakers missed the interest rate deadline despite the fact that they had a pair of thoughtful proposals for how to proceed. The House passed a bill in May that would put federal direct student loans on sustainable footing for the long term, and a bipartisan group of senators recently offered a similar, more centrist measure. Both proposals would switch the federal direct loan program from fixed to variable interest rates and tie the rates to the government’s cost of borrowing money (specifically, the interest rate paid on 10-year Treasury notes).

The problem is that lawmakers waited too long to take up the issue, even though they gave themselves a year to work on it last June.

That’s what Democrats would have you believe, at least. Although several top Democrats (including President Obama) have endorsed switching from fixed interest rates to variable ones for student loans, they’ve rejected proposals to do just that in favor of extending the current, fixed rates for one or two years to give Congress more time to address all issues related to college affordability.

Granted, it makes sense to look at loan interest rates alongside other forms of aid and steps to hold down college costs (more on that point later). But this argument would be a lot more credible if Democrats hadn’t pleaded for more time last year as well. They prevailed -- Congress kept the interest rate on subsidized Stafford loans at 3.4% for 12 additional months -- but the implicit promise was that lawmakers would come up with a long-term solution during that period. (In the subsidized version of Stafford loans, the federal government pays the interest until the borrower leaves college.)

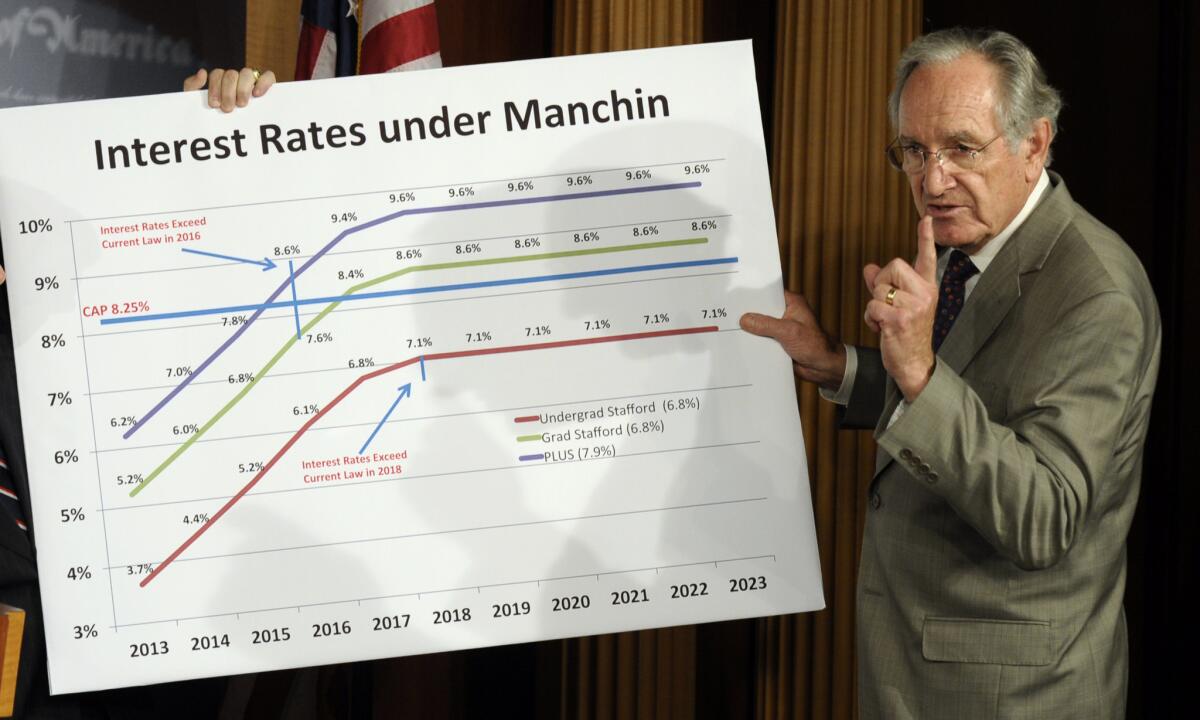

The bipartisan Senate bill by Sens. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.), Richard Burr (R-N.C.) and four others lays out a durable framework for direct loans that, with some tweaking, should be acceptable to both sides. By shifting all forms of direct loans to variable rates, it would immediately lower the interest rate on nonsubsidized loans by 2 to 3 percentage points. Unlike the House bill, the interest rate would be fixed for the life of the loan, although each year the rate for new loans would be adjusted to reflect changes in the government’s borrowing costs. And the rate would be set as low as it reasonably can be without forcing taxpayers to subsidize the direct loan program. Some Democrats would like to go that additional step further, but the government already spends billions of dollars subsidizing students through Pell grants and other forms of aid.

The two sides have a legitimate disagreement over some of the details, such as what sort of ceiling to set for the adjustable rates and which Treasury bills to use as a baseline. But rather than working out a compromise on those issues, top Senate Democrats are pushing a bill that would kick the can down the road for another year. To pay for the one-year rate freeze, they would force most taxpayers who inherit retirement savings accounts to cash them out (and pay taxes on the proceeds) in five years, rather than spreading the disbursements over their expected lifetimes. Now that’s good policy -- force people to spend their savings faster!

Having said that, I’ll gladly concede that interest rates are just one piece of the puzzle here. Some economists contend that the availability of low-cost financing for college only exacerbates the problem of rising college costs. Although it makes sense intuitively that increased federal aid is connected in some way to higher tuition, the data don’t support a simple cause-and-effect relationship. The clearest link is between state support for higher education and public college tuition: When states put up less money for their colleges and universities, tuition goes up.

My Times colleague Michael Hiltzik recently argued that lawmakers should focus less on interest rates and more on income-based repayment plans, which hold down loan payments for graduates with smaller paychecks. Others contend that Congress should bring market forces more squarely to bear on college costs. Law professor Glenn Harlan Reynolds lays out a few ideas in Friday’s Wall Street Journal, such as billing colleges for part of the cost when their former students default on their loans.

These are all issues for Congress to explore as it updates the Higher Education Act, which expires at year’s end. In the meantime, though, lawmakers should work out a deal on direct loan interest rates.

ALSO:

Paula Deen is still trying to poison us

Muppets and marriage: The New Yorker hitches Bert and Ernie

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.