Editorial: Ding dong. Repeal and replace is dead. (For now)

- Share via

Early Friday morning, the U.S. Senate came within one thin vote of dropping a megaton legislative bomb on the health insurance markets serving roughly 1 in 10 Americans. Republican senators were so eager to keep their promise to repeal the 2010 Affordable Care Act, yet so unwilling to compromise on a coherent approach to unwinding the law, that 49 of them backed an eight-page, lowest-common-denominator proposal that seemingly every major healthcare trade association and patient-advocacy group had warned would be disastrous for all concerned. The measure even attracted the support of three senators who’d dubbed it a fraud and pledged to vote “yes” only if they were assured the House wouldn’t pass the thing into law.

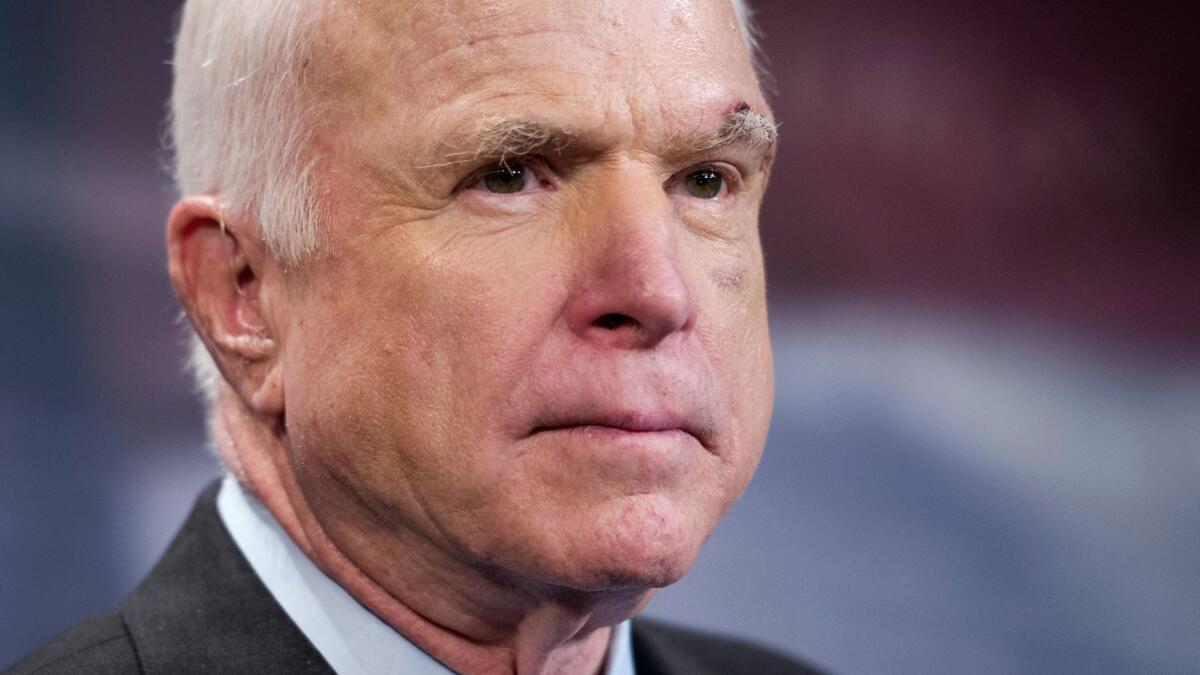

Three other GOP senators bravely joined all 46 Democrats and two independents in voting against the so-called “skinny repeal” proposal, which Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) unveiled late Thursday night after days of closed-door negotiations within the GOP caucus. But the willingness of Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and John McCain of Arizona to part company with their colleagues isn’t nearly as remarkable as the spectacle of 49 Republicans blithely voting in favor of a bill that would have quickly made health insurance unavailable or unaffordable to millions of their constituents — a measure that hadn’t even been seen, let alone subjected to the ordinary legislative process of hearings and debate, until two hours before it was brought to a vote.

McConnell pulled out all the stops to keep the “repeal and replace” effort alive, even delaying the final vote for a tense hour while Vice President Pence buttonholed McCain on the Senate floor. But the dissenters (thankfully) held their ground.

Vice President Pence buttonholed McCain on the Senate floor. But the dissenters (thankfully) held their ground.

It was easy for Republicans to vow to repeal Obamacare when they knew they couldn’t actually do it. Now that they have the numbers and the White House, they’ve learned that not all of them actually want to undo two of the fundamental changes wrought by the act: letting states extend Medicaid to more lower-income people largely at federal taxpayers’ expense, and barring insurers from favoring healthy customers over sick ones in the non-group market. The GOP was also divided over a push by conservatives to rein in spending on the traditional Medicaid population of very low income pregnant women, children, elderly and disabled Americans.

Expanding coverage to lower-income Americans is expensive, but bringing everyone under the insurance tent is not just humane — it’s essential to the efforts to slow the growth in healthcare costs by changing how care is delivered and financed. It’s also worth noting that Medicaid’s costs have been rising more slowly per person than the per capital costs in Medicare and private insurance.

And it’s ridiculous to think that Americans without health insurance at work would be better served if insurers could once again separate the healthy among them from everyone else. Yes, some people would be happy to buy cheaper policies that covered fewer risks. But that would only make it more expensive to buy a comprehensive plan, or coverage for preexisting conditions, or maternity coverage — or just about anything else that someone might actually need.

The demise of repeal and replace is welcome. Yet there are still problems for Congress to tackle. Although the individual insurance market shows signs of stabilizing on the whole, it’s unraveling in several states as premiums rise rapidly and choices dwindle. The instability has been exacerbated by the Trump administration threatening to withhold an estimated $7 billion worth of payments to insurers for the subsidies the law requires them to provide to low-income customers who can’t afford their deductibles and co-pays. The administration also has taken steps to weaken the law’s requirement that Americans carry insurance — a requirement that prevents healthy people from gaming the system and obtaining coverage only when they need costly treatment. Without an effective mandate, insurers are left covering sicker, riskier customers, sending premiums into an escalating spiral and rendering coverage affordable only to people receiving subsidies.

The GOP “repeal and replace” proposals wouldn’t have solved those problems, unfortunately. They would only have shifted costs onto those who want or need more comprehensive coverage, then tried to paper over that problem by ponying up tens of billions of dollars in federal aid to insurers and their customers. Please keep that in mind if Republicans blast Democrats for seeking an insurer “bailout,” as McConnell did Friday morning.

The “skinny repeal” plan was the worst idea of all. By proposing to repeal the requirement to obtain insurance without providing any other barrier to gaming the insurance system, it would have invited healthy people to abandon the individual insurance market in droves, leading insurers to jack up premiums or withdraw their policies. And it would have happened right away, because insurers are deciding now what to offer in 2018. The Congressional Budget Office warned that the measure would lead to 16 million more people going uninsured next year, an increase of almost 60%.

McCain urged his colleagues again on Friday to do something Democrats failed to do in 2010: pass a truly bipartisan healthcare bill. The two sides are far apart on Medicaid, but not necessarily on how to bring more competition and affordability to the individual market. The issue is how to spread risk and cost more broadly, and there are good ideas from both camps. Lawmakers should focus on the latter challenge, and do it now.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.