California’s pink-slip shuffle

- Share via

“Dear Miss Bhakta,” read the note. “Thank you for making this my best year in school ever! And congratulations, you deserve it!”

The congratulations were for winning my school’s 2009 Teacher of the Year Award. It had come with hugs from other teachers, glowing notes and emails from parents, and a laudatory letter from the principal. What I cherished most, though, were the words of appreciation from students themselves — words that said I was making a difference.

I was still smiling about the note when the principal came to my classroom. Her eyes were red with tears, and the moment I saw her I knew what was coming. Moments like this are all too familiar to teachers without much seniority in California. She was giving me a pink slip, warning me that I was at high risk of being let go, as so many caring and talented teachers are every year because of budget cuts. Sometimes the pink slips are rescinded at the last minute; sometimes they aren’t. But the system has forced many excellent teachers out of teaching and into more stable professions.

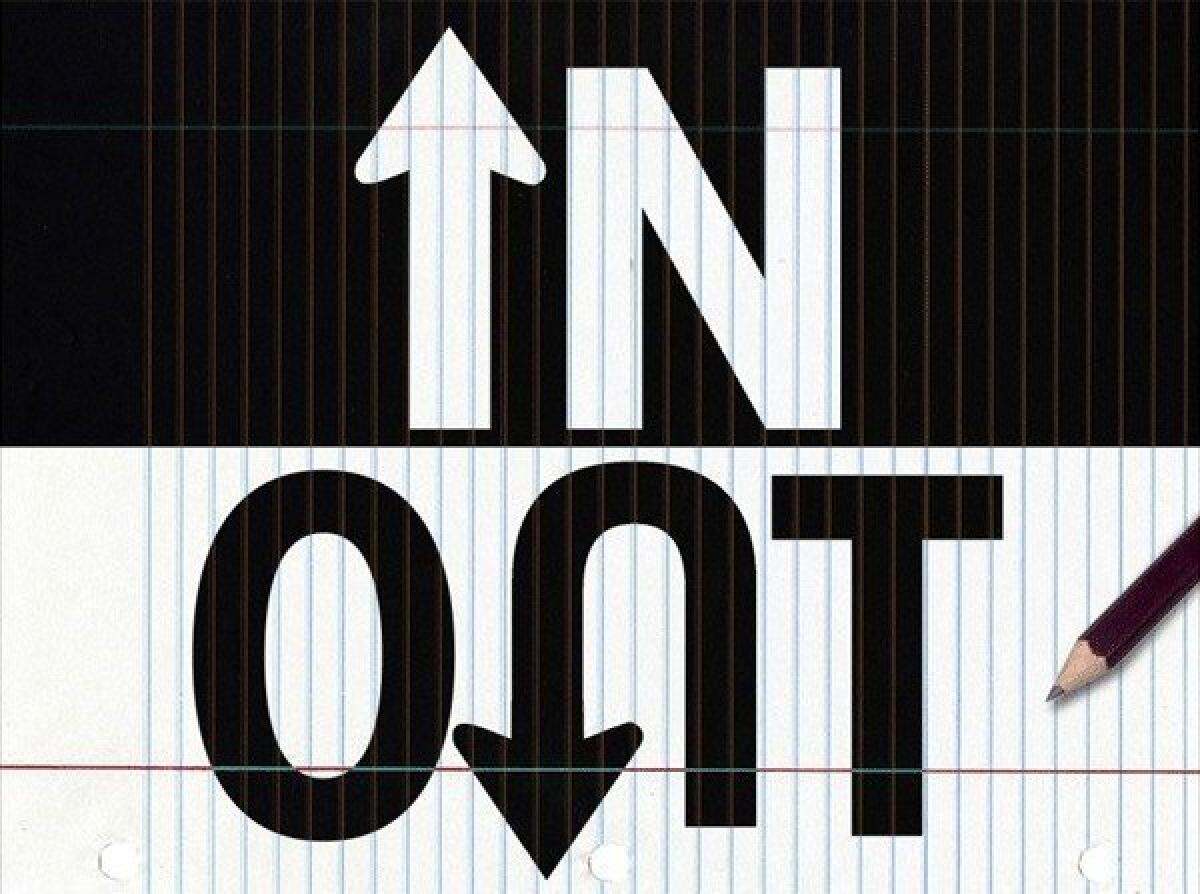

The annual madness is the result of LIFO, which stands for “last in, first out.” It is currently the law in California, and what it means is that school administrators must make teacher retention decisions based solely on seniority, without regard to a teacher’s effectiveness in the classroom. LIFO is the functional equivalent of an NBA team being forced to fire LeBron James because a bench warmer on the team has more years in the league. In the case of schools, it can mean that 30 or more children who have only one shot at, say, third grade, are being taught by an inferior teacher

LIFO’s tag-team partner in the substandard education derby is California’s antiquated tenure system. Under current law, teachers receive tenure after only 18 months of work and minimal administrative review; there is virtually no evaluation process to determine whether teachers are effective before receiving tenure, and after receiving it, tenured teachers are virtually impossible to fire.

The legal roadblocks to firing a tenured teacher are so formidable that even abject ineffectiveness is not considered a fireable offense. In a recent survey, 68% of teachers said they knew of at least one grossly incompetent teacher at their school who deserved to be fired but had not been.

The combined results of LIFO and the tenure system can be catastrophic for students. Multiple studies have shown that even a single year with an ineffective teacher can set students back for a lifetime. They are less likely to graduate from high school, less likely to attend college, and will on average earn lower incomes compared to peers who had the good fortune to be taught in that year by an effective teacher.

Effective teaching, on the other hand, is the single largest predictor of students’ success, eclipsing even such important factors as parent involvement and socioeconomic status. Administrators, parents and students already know this intuitively; little wonder, then, that I have seen both students and parents in tears upon discovering that the high-quality teacher they were counting on had been “LIFO-ed” and replaced by a teacher who was known throughout the district for being ineffective.

The good news is that we do have the ability to increase teacher effectiveness. Study after study has pointed to the need for regular, comprehensive evaluations of teachers. These should include repeated class observations by administrators and other teachers, objective measures such as student test scores and regular written evaluations from fellow teachers, students and parents. But that’s only one step. It is also clear that continued employment as a teacher should be linked to effectiveness. Administrators should be given the ability to hire, fire and reward teachers based on their performance in the classroom.

Why has California not implemented these measures? The primary reason is that teachers unions have strongly opposed changes to LIFO and tenure. Not only do they value teachers’ rights over students’ rights; they also value some teachers over others. In protecting those with the most seniority, the unions are turning their backs on newer teachers. And they are also completely out of touch with what most rank-and-file teachers actually do want: a system that rewards effectiveness, encourages improvement and weeds out blatant incompetence.

The good teachers I know believe that every student has a right to the best possible education. We need to stand together with students and parents to challenge LIFO and the tenure system.

One year, during the annual cycle of layoffs, I received a summons to the district office to conduct a “tie-breaker” with other teachers who had the same level of seniority as I did. I refused to attend, but those that did were told that cuts had to be made and that the district was not legally allowed to choose between us on the basis of merit. The personnel director held a basket with numbered tiles and the teachers proceeded to “draw straws” to see who would be teaching the following year.

I won’t tell you the result because you already know it: As long as we have a system in which teacher effectiveness plays no role in retention decisions, it will always be students who get the short straw.

Bhavini Bhakta lost teaching positions in four schools over eight years because she lacked seniority. She now teaches fifth grade in Arcadia. She worked on this piece with Students Matter, an organization that is challenging California’s teacher protection laws in court.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.