Op-Ed: To fight Ebola, create a Health Workforce Reserve force

- Share via

A recent projection of the West Africa Ebola outbreak is that it now may take 12 to 18 months to control and will infect 100,000 people. President Obama announced the deployment of 3,000 military troops, more than a hundred Centers for Disease Control and Prevention personnel and millions of dollars to help stem the tide.

How did the outbreak get so out of control?

The answer is partly rooted in where Ebola struck. Health systems in the post-conflict states where it hit first and hardest were already in tatters. And the crisis has been exacerbated by a woeful shortage of healthcare workers worldwide: The World Health Organization estimates the shortage at 4 million workers, with the burden hitting Africa disproportionately. The continent has 25% of the global disease burden but only 3% of the world’s health workers.

What this has meant is that, when crises strike, a patchwork of nongovernmental organizations and outside government agencies has tried to step in and fill the need. In this situation, for example, Doctors Without Borders, an NGO working in more than 60 countries, accounts for two-thirds of the treatment and care being provided in the regions affected by Ebola. The group’s workers have shown incredible valor and stamina, but Doctors Without Borders alone cannot possibly control an epidemic of this size.

The epidemic is also beyond the ability of WHO to contain. In recent years, the agency’s budget has been slashed and experienced personnel have left. WHO now operates on a budget that is less than the annual budget of many hospitals in the United States. In response to cutbacks, WHO has closed its pandemic and epidemic response team, which had proved enormously effective in outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome.

The world needs a new approach to solving massive international health crises and preventing future ones. Taking as our model the U.S. military reserve forces, we propose the formation of a Global Health Workforce Reserve, in which trained physicians and nurses with experience in low-resource settings enlist for a period of time. By joining the reserves, they would agree to be deployed when needed for epidemics and catastrophic events. Such a corps could be scaled up quickly and would be centrally managed by WHO or the United Nations.

Recruits would go through short-term boot camp training for disaster relief and outbreak management, then would attend occasional additional training during their enlistment. Given the interest in global health training programs in the last 10 years, as documented by the Consortium of Universities for Global Health, we think there would be no dearth of volunteers.

Indeed, healthcare workers swarmed to volunteer after the Haiti earthquake and Indonesian tsunami, but although the workers themselves were well-intentioned, efforts to use them were often disorganized and ineffective. Currently, the president of Doctors Without Borders is calling for emergency response teams from around the world to help in the battle against Ebola, and individuals, countries and NGOs are responding. But think how much more effective a centrally deployed Global Health Workforce Reserve would be in such a situation.

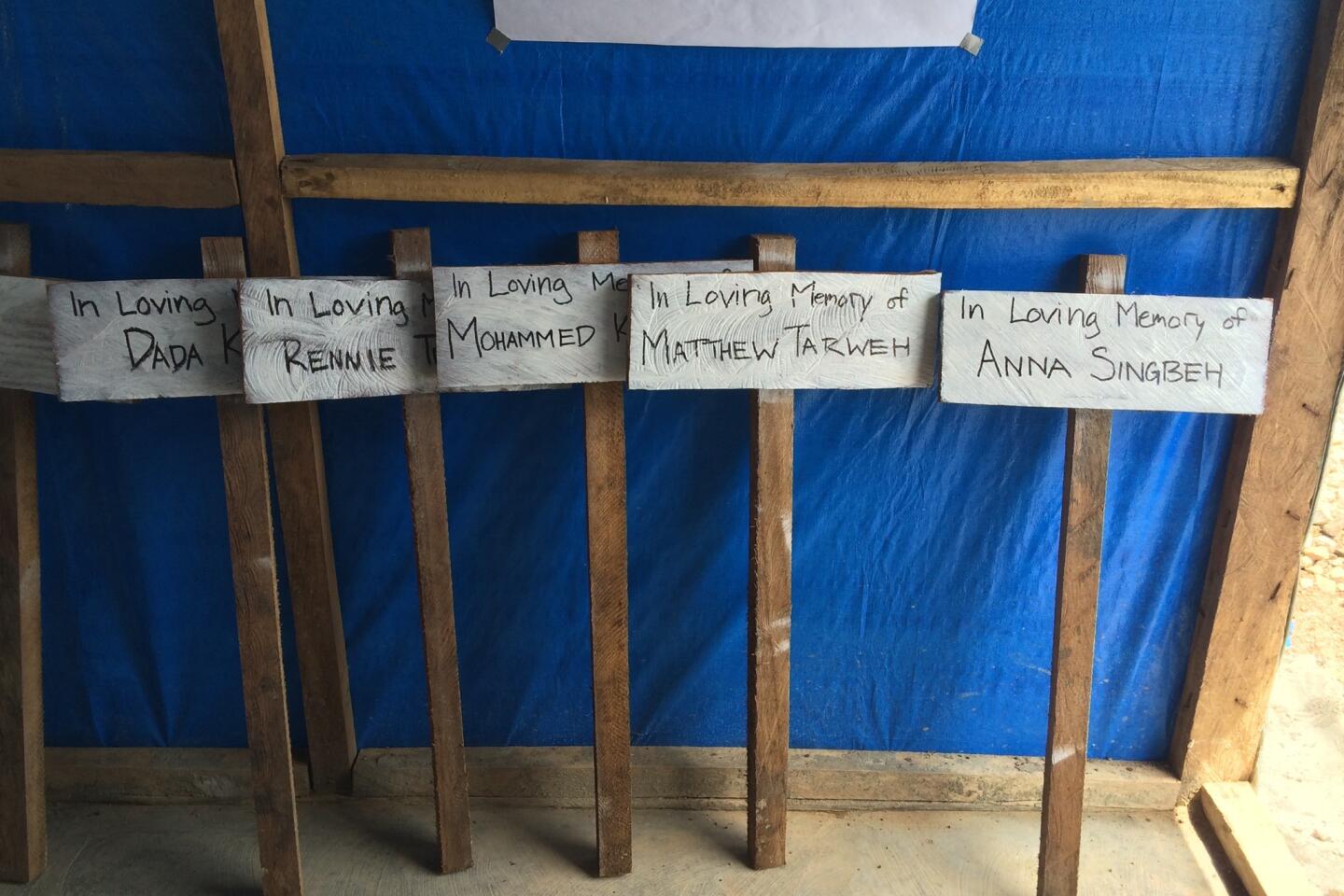

In the end, the Ebola crisis can’t rely on scarce, untested drugs or vaccines, mass quarantines or even airdrops of personal protective gear. The reason the outbreak has turned into a tragedy is rooted in the region’s fragile health systems and human resource shortages. The situation can’t be addressed in the long run without addressing these fundamental structural deficiencies, which could be part of the job of a reserve corps.

In the same way that U.N. peacekeeping units help defuse tensions in unstable regions, these healthcare professionals could bolster scarce medical personnel and potentially offer a coordinated response to health catastrophes.

In the long term, it will be necessary to help poor countries build their own health systems, with trained domestic workforces able to prevent epidemics and provide humane care and treatment. That will take time and substantial resources. But in the interim, a Global Health Workforce Reserve would cost a tiny fraction of what is currently spent on international health assistance. The World Bank could take a leadership funding role, and WHO or the U.N. could house a central unit able to call up the reserve and deploy nurses and doctors.

The West African Ebola epidemic is a tragedy. But perhaps it can point the way, ultimately, to offering a sturdy medical lifeline to poor countries and preventing uncontrolled spread of epidemic diseases.

Michele Barry is senior associate dean for global health and director of the Center for Innovation in Global Health at Stanford University. Lawrence Gostin is a professor and director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.