Op-Ed: Is a prisoner’s beard dangerous?

- Share via

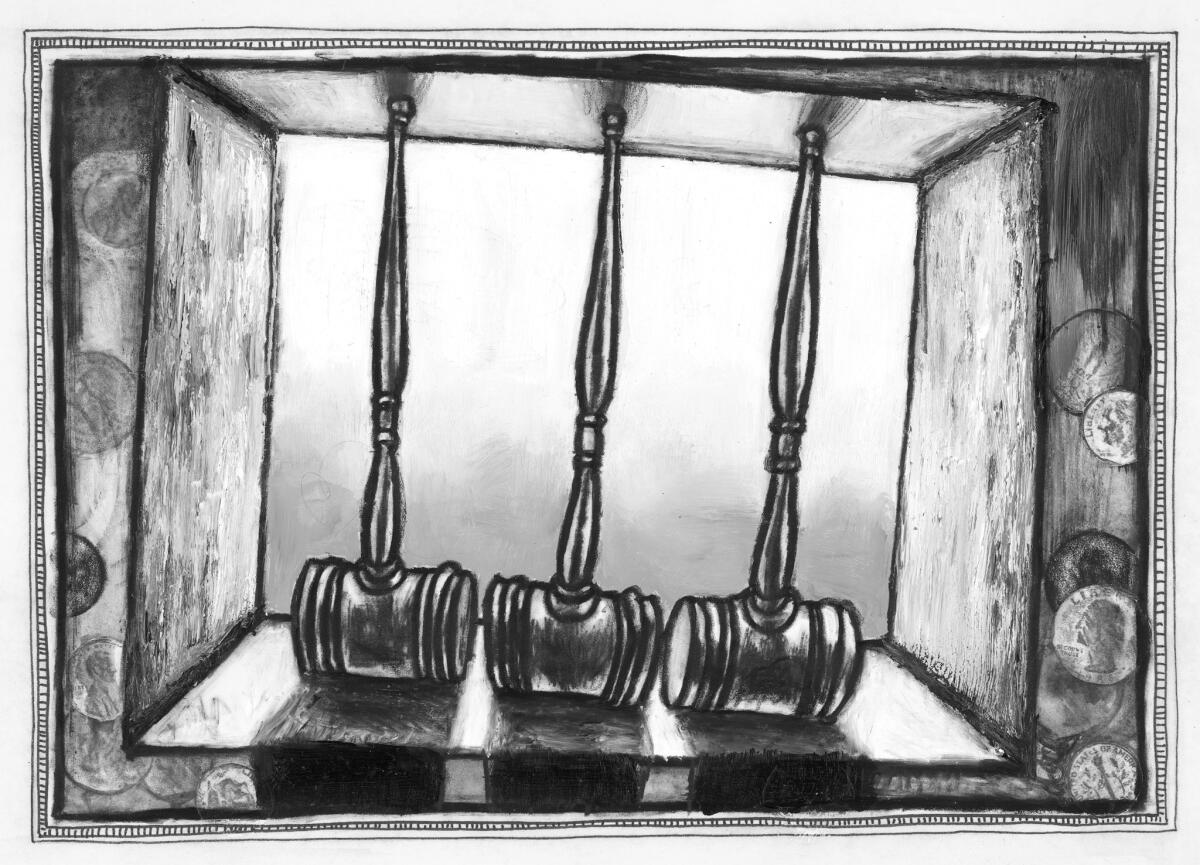

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Holt vs. Hobbs, another big-ticket case that tests the limits of religious liberty when it comes into conflict with government regulation. The petitioner — Gregory Holt — is a prison inmate, housed by the Arkansas Department of Correction. But Holt is also known by another name, Abdul Maalik Muhammad, and he is by all accounts a sincere adherent of Islam. As part of that faith commitment, he wants to grow his beard 1/2-inch long in accordance with Islamic practice.

It seems like a relatively reasonable request. But Arkansas prison officials have refused to grant it, arguing that a 1/2-inch beard would prevent them from maintaining the safety and security of the prison. The Department of Correction contends that Holt might be able to hide, for example, a SIM card or a razor in such a beard; the former could be used to order contraband and the latter to commit further violent crimes.

To address these types of cases, Congress passed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act in 2000. The act says prisons may not impose regulations that “substantially burden” the religious liberty of inmates. The exception is a regulation that is the “least restrictive means” to advance a “compelling government interest.” Put more succinctly, carefully tailored regulations necessary to accomplish something extremely important are permissible.

In Holt’s case, the Arkansas officials argue that they have followed the legal formula: The policy, they claim, is necessary to protect the safety and security of prisons.

But there is good reason to be skeptical that the prison’s beard policy is truly necessary.

Arkansas already allows prisoners to grow a 1/4 -inch beard if for a medical reason they cannot shave. In addition, 44 states have policies that would allow Holt to grow a 1/2-inch beard, and the Arkansas brief before the Supreme Court conspicuously lacks any examples where those policies have led to death and destruction within a prison’s walls.

Nor, apparently, have the prison officials considered or tried any obvious alternatives in pursuit of safety and security. In fact, one Arkansas warden has already admitted under oath that he never explored how other jurisdictions implemented their more lenient beard policies. For example, a prison could allow 1/2-inch beards but also require that they be regularly inspected, perhaps by having the inmate run his fingers through his beard under the direction of a prison guard.

The prison officials are asking the court to ignore all this. Their position, in short, amounts to the following: “Trust us — we are the experts.” It argues that the court must defer to prison officials when they claim that a particular regulation is the only way to protect the safety and security of the prison environment.

But the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, which was sponsored by Sen. Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah) and the late Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.), requires far more scrutiny of prison regulations. As Hatch and Kennedy wrote when the law passed, “Prison officials sometimes impose frivolous or arbitrary rules.” And so the act expressly demands that the government explain why there is no other option available before it substantially burdens an inmate’s religious practices. Otherwise, prisons would have a free hand to prioritize bureaucratic convenience over fundamental religious liberties.

The Supreme Court, unfortunately, has an embarrassing history when it comes to exchanging our civil rights for supposed security. During World War II, the federal government infamously prevailed before the court when it argued that Japanese internment camps were necessary to protect the safety and security of the American people. In retrospect, the court simply failed to question why interning U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry was necessary to protect national security; indeed, even the most limited interrogation of the claim would have exposed the camps for what they were: outright discrimination.

The Arkansas Department of Correction’s claim that its beard policy is necessary to protect safety and security must be scrutinized. Indeed, it is hard to imagine the claim surviving much scrutiny at all. Prisons may be dangerous places, but that does not mean we can allow them to infringe on civil rights without justification. When it comes to abridging civil rights, we must hold government accountable. “Trust us” is just not enough.

Michael A. Helfand is an associate professor at the Pepperdine University School of Law and associate director of the Diane and Guilford Glazer Institute for Jewish Studies.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.