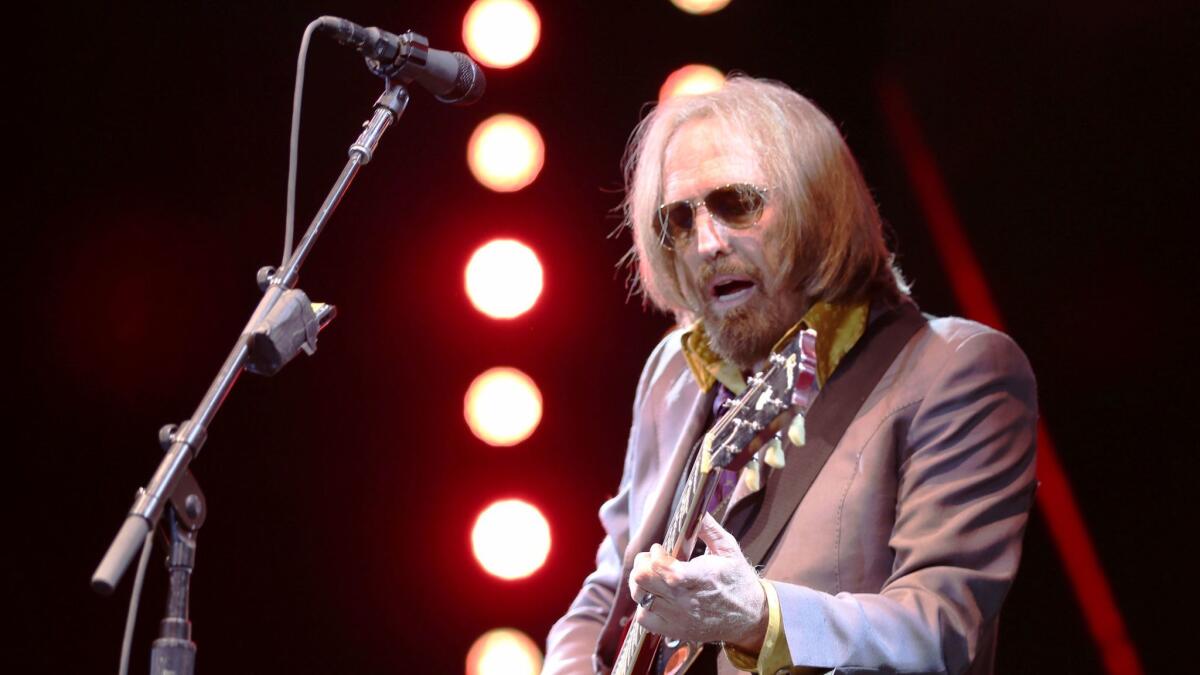

Op-Ed: That time Tom Petty wouldn’t back down

- Share via

There was something so Tom Petty about the way the news arrived. How the CBS report that he died the morning of Oct. 2 was later rescinded. Even in the way that the hours between the false reports and the official announcement allowed Petty fans to imagine that the man who sang “I won’t back down” was, in his last moments, not backing down.

Few outside the music business know just how accurate those lyrics were. Within it, the story is canonical. Decades before Prince changed his name to a glyph and compared the major-label system to indentured servitude, Petty took on the entire industry, waging a battle for his music rights that changed forever how artists negotiate with record companies.

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers had released two hit albums when, in 1978, their label, Shelter Records, announced it was going to be sold by its parent company, ABC Records, back to what had been the label’s original parent company, MCA.

Petty, a scrappy 28-year-old punk from Gainesville, Fla., had been in the business for only a few years, but that was enough time to have acquired a simmering rage. Believing that “publishing” referred only to sheet-music songbooks, he had signed over 100% of his songwriting rights for a $10,000 annual advance. He soon managed to get some of those rights back, but it left a mark. “My songs had really been taken away from me when I didn’t even know what publishing was,” he said.

In standing up to MCA, Petty demonstrated the premise that an artist with fans has leverage.

The Heartbreakers’ record deal was almost as bad as Petty’s publishing deal. And, as is routine, although the record company fronted the Heartbreakers money to make their albums, those costs were deducted against the band’s meager royalties.

When it was announced that the Heartbreakers would be transferred to MCA, Petty balked. “I just felt like they sold us like we were groceries, or frozen pork,” he said.

Petty had an out. As part of a previous renegotiation, he had managed to add a clause to the Heartbreakers’ deal stipulating that their label, Shelter, must consult with him before selling the band’s contract to another company.

That clause gave Petty plausible grounds to claim that Shelter had breached their contract, and that he was therefore free to shop for a new label. But when he moved to act on that premise, MCA and Shelter sued Petty for breach of contract, preventing him not only from negotiating with other labels but also from releasing music or playing live.

What did Petty do? Like so many artists do today, he self-funded the recording of the band’s third album, racking up more than $500,000 in debt. Then, when MCA’s lawsuit left him legally unable to do anything with it, he filed for Chapter 11. “Technically you’re bankrupt,” he later said. “And if you’re bankrupt, all contracts are void.”

Petty was the first mainstream rock star to file for bankruptcy expressly to get out of a contract with his record label. And because he was the first, MCA had to make sure he didn’t succeed. “As soon as they thought my action might set an industry precedent,” Petty explained, “they rolled out the big guns.” So began one of the most epic games of chicken in music-business history.

The companies tried to persuade Petty to drop the bankruptcy claim, to which he responded: “I’ll sell …. peanuts before I give in to you.” In one meeting with MCA’s lawyers, Petty’s manager later said, Petty “had a penknife that he got out, opened the penknife and started cleaning his nails.” To pay for their legal bills, the Heartbreakers went on a short tour, the “Lawsuit Tour.” They wore T-shirts that said, “Why MCA?”

In the end, Petty reconciled with MCA, signing a deal with an artist-friendly label under the MCA umbrella, and the rest, of course, is Billboard chart history. The Heartbreakers’ next album, “Damn The Torpedoes,” went triple platinum, unleashing two of Petty’s most omnipresent songs on the radio, “Don’t Do Me Like That” and “Refugee.” (“Somewhere, somehow, somebody must’ve kicked you around some,” he sings in the latter.) In all, Petty recorded some 68 singles, a record 28 of which became mainstream-rock top 10s.

In standing up to MCA, Petty demonstrated the premise that an artist with fans has leverage. He used that leverage over and over. He did it in 1981, when MCA tried to sell the band’s fourth album for a dollar more than the standard. And he did it in the late 1990s, when he capped his concert ticket prices at $50.

Although many Petty songs illustrate why he enjoyed such an unparalleled career (a word he wouldn’t use, apparently), it’s a sly lyric buried in 1991’s “Into the Great Wide Open” that may mean the most for recording artists. The song tells of Eddie, a young kid who moved to Hollywood and started a band. They made a record, “met movie stars, partied and mingled,” Petty sings, before delivering the gut punch: “Their A&R man said, ‘I don’t hear a single.’ The future was wide open.”

Gary Jules is a singer-songwriter.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

ALSO

Why losing Tom Petty feels like losing a piece of ourselves

The heartbreaking Instagram dispatches Tom Petty’s daughter sent as the rock star clung to life

Musicians, creators and celebs react to the death of Tom Petty

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.