Op-Ed: An Afghan American recalls a childhood spent straddling cultures at war

- Share via

A few days after 9/11, I stood on the blacktop of my elementary school in West Sacramento assuring my best friend that Afghanistan had nothing to do with the attacks on the World Trade Center. I was 9 years old. I knew nothing about Osama bin Laden, Al Qaeda or the Taliban.

What I did know was that I’d visited Logar province in Afghanistan and the people there were very sweet and very loving and incapable of such destruction.

“It wasn’t us,” I told my friend. But, apparently, it was.

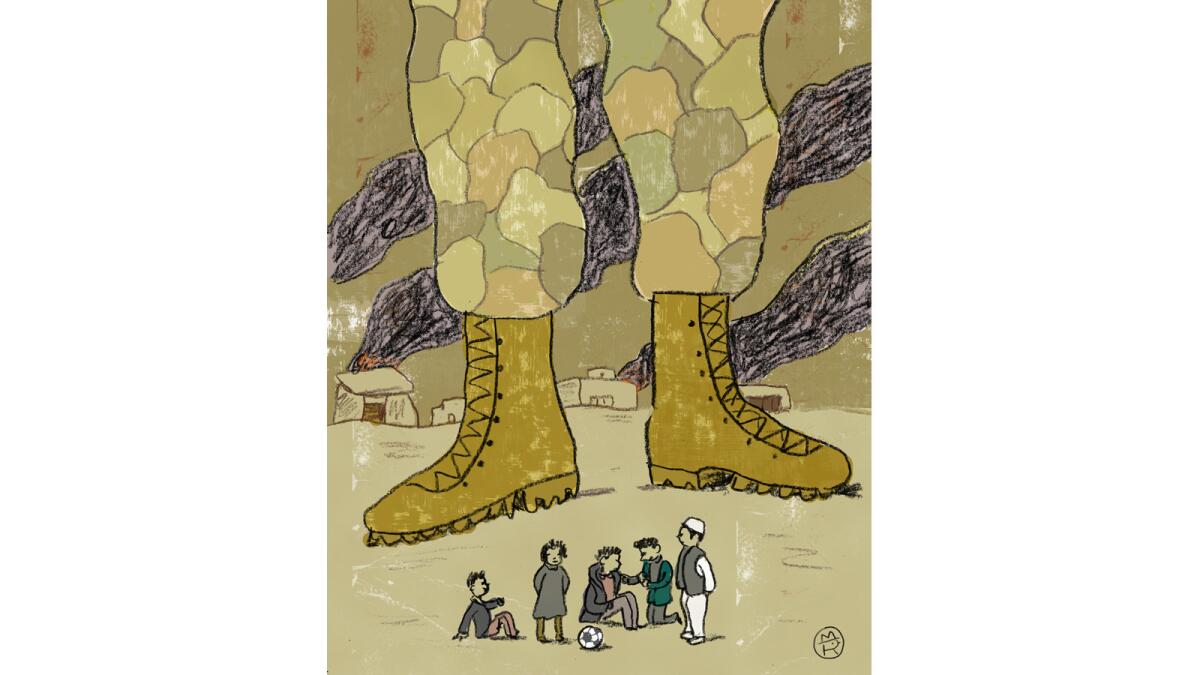

Several weeks later, on Oct. 7, 2001, the United States carried out air strikes on Afghan soil. Operation Enduring Freedom , the official name for America’s global war on terrorism, would go on to slaughter approximately 38,480 Afghan civilians, according to a Brown University study. The U.S. forces quickly toppled the Taliban, took over Kabul and began their occupation.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

A few months after the invasion, the FBI, perhaps hearing about the legendary hospitality of the Pashtuns, came to visit our home. Without looking through the peephole or waiting for an adult, I opened the door to find two white men wearing dark suits. They asked for my father and I called out his name.

From the safety of the kitchen, I spied on the spies as they questioned my father about his short-lived career as a member of the mujahedin during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Once they determined that he wasn’t a security risk, the agents left the house, but not our lives. My family and I — along with most of the Muslim community — would be surveilled, questioned, misrepresented and harassed.

When I was about 10, I asked my father about the war on terrorism, the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan and the rise of the Taliban. He answered my questions calmly and carefully, but after he finished, he warned me to never discuss any of it at school.

I couldn’t explain to him why this would be difficult.

A year or so into the occupation, Bin Laden was somehow still evading the U.S. military, and my classmates, seemingly eager to help, asked me, over and over, where Bin Laden was hiding. They had a funny way of putting it.

“Where’s your grandpa?” they used to say.

Or “Where’s your uncle?” Or “Where’s your pops?”

It was a joke, of course, and mostly I laughed. And yet, after I heard the joke from so many different people, in so many different scenarios, the link between my family and Bin Laden began to weigh on me. This was compounded by consistent representations of Muslims, and especially Afghans, as terrorists and militants in film, television shows and video games. The cumulative pressure forced me to see myself in the Talib, the sleeper cell, the suicide bomber.

I despised Bin Laden, Al Qaeda and the Taliban more than anyone else I knew. But the constant association between Islamic militancy and my ethnicity also made me question American assumptions about these militants. Was Al Qaeda just inherently monstrous? Was the militants’ brutality psychopathic? Ideological? Or did poverty and war drive them toward violence?

Over time, the American part of me felt violently at odds with the Afghan part. The term “Afghan-American” itself disturbed me. Rather than being a point of unification, the hyphen seemed to reveal a sort of chasm, a rupture, inside of which rested all the violence and contradictions of the American war.

If I hadn’t been to Afghanistan, if I hadn’t already fallen in love with Logar, my sense of exclusion, of demonization might have broken me down. But I knew Logar.

I was 12 when I returned in 2005. My family spent three months in my parents’ home village in Mohammad Agha district in Logar. This was a time of relative security in the country. The Americans were building and manning security checkpoints, living in barricaded compounds cut off from the native population and still holding, even torturing, terror suspects at dark sites. The Taliban held very little territory; the insurgency was mostly under wraps.

For a kid, there was a lot to love about Logar. The streams and the apple orchards, the mulberries and the singing birds, the fish and the mountain breeze and, best of all, my cousins and little uncles, who didn’t care about me being American, who just abounded with affection in a way you never really see with boys in West Sacramento. It was all hugs and hand-holding and love songs.

Still, the war went on. In the black mountains, bombs exploded through the night. In the markets, U.S. soldiers patrolled the streets sitting atop behemoth Humvees, always strapped. In the air, the smell of grain and flowers mingled with the constant stink of smoke.

And then there were the stories. Nightmarish tales told by my cousins about American soldiers pissing on the Koran, raping women, massacring families. When I asked my cousins where and when these incidents occurred, they seemed confused. It’s happening everywhere, they said, all the time.

Everything in Logar — the mountains and the stories and the land itself — seemed frightening and beautiful all at once. I was conscious of myself and of my surroundings in a way I never experienced in the U.S. I went about Logar in fear, in awe, feeling free and alive. And once I returned to the States, I searched everywhere for that same sense of awe, of frightening beauty, and I couldn’t find it. There were times when I was outside, maybe playing basketball at the park, maybe stuck in traffic, and I would catch a whiff of something burning and be transported back.

I started to read more about Afghanistan. Historical texts, news articles and reports on war crimes.

“On April 29, 2007, at least 25 Afghan civilians were killed during airstrikes in support of U.S. Special Operations Forces operating in the Zerkoh Valley. … Afghan government officials said that they counted 42 civilians dead from the bomb attacks. They said that they found no evidence of Taliban forces in the area and that local residents were adamant there were no Taliban forces there at the time.”

“On the morning of July 6, 2008, a wedding party was hit by an … airstrike near the village of Kacu. … The death toll [was found] to be 47, which was also confirmed by human rights officials.”

On Sept. 4, 2009, “an American fighter jet bombed two hijacked fuel trucks in northern Afghanistan, killing scores of people and prompting accusations that many were civilians.” In January and February of 2010, U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan “murdered civilians for sport.” On March 11, 2012, Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales broke into three homes in three different locations in Panjwai district and murdered 16 people, nine of them children, and wounded five others. Some of the bodies were set on fire.

The next time I went to Afghanistan in 2012, I spent a few weeks in Logar, but by then government militias were patrolling the roads during the day and the Taliban ran the village at night. My relatives warned me not to tell anyone who I was or where I came from. In West Sacramento, I felt protected by my legal status as an American, but in Logar, it put my life at risk.

Even so, my days in Logar were joyful. I worked on the land with my uncles. I cut and hauled wheat. I pulled weeds and picked berries. I fed the cows and the chickens, and for moments at a time, when I didn’t speak, when I knelt in the fields and saw the sun dipping behind the black mountains, I almost felt like a true-to-life Logari.

Over the years, while I studied in the States, the security situation in Logar deteriorated. Much of my family fled our hollowed-out village, lost to the war. When I visited in 2017, we took just one quick trip back — my father, his cousin, my brother and myself. We prayed at the marker of my father’s murdered brother, Watak, who had died during the Soviet war, and at the graveyard where two of my uncles were buried. Get in, say your prayers, get out. The empty trails in Logar, and the wind howling in the orchards made it seem as if I was living inside a memory.

I am still haunted by the Logar of my childhood, a place lost to time, to diaspora and to war. I can barely imagine myself at 12, walking the trails of Logar, surrounded by my cousins and little uncles, some of whom are now soldiers, some of whom have fled Afghanistan, some of whom who have been martyred.

But back then, even amid the occupation, we chased chickens and climbed trees and ran through cut fields of wheat. We cursed at soldiers, at drones, at death. We played and danced and fought and lied and wept and prayed and crept, and sometimes we held hands so tenderly that it frightened this confused boy from America, who did not know such tenderness could exist amid war, and who would be marked forever by its loss.

Jamil Jan Kochai’s first novel “99 Nights in Logar” was published in January.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.