Opinion: Netflix, ‘zero rating’ and the net-neutrality drama

- Share via

Responding to the pleas of millions of American Internet users, the Federal Communications Commission is poised to adopt tough net-neutrality rules that treat Internet service providers as utilities subject to Title II of the federal Communications Act.

Now here’s the irony. Many of those public comments were inspired by outrage over something ISPs have done that doesn’t technically violate net neutrality. Meanwhile, something ISPs are doing that looks an awful lot like a neutrality violation hasn’t drawn a peep of protest from ordinary consumers.

The debate over neutrality rules has been based largely on hypotheticals and worst-case scenarios. Advocates of the rules, including President Obama and FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, say they’re necessary because ISPs could pick winners and losers online by blocking or slowing down some sites’ traffic while providing a fast lane for others. Although this sort of manipulation isn’t happening now, they say, it could strangle innovation and economic opportunity online if it does.

That’s a valid concern, considering the stakes involved and the paucity of competition in residential broadband. But it’s not much of a rallying cry. For that you’d need an actual example of ISPs behaving badly.

Enter Netflix, whose streaming service has 39 million U.S. subscribers. The service’s video streams make up more than a third of the downstream Internet traffic during primetime, Sandvine reported late last year. There was so much demand, in fact, that the “transit” companies Netflix paid to deliver its streams to its customers were hitting a logjam when they connected to some of the biggest residential ISPs. Those customers endured the poorer quality pictures or, worse, frequent interruptions in their videos as the streams paused to rebuffer.

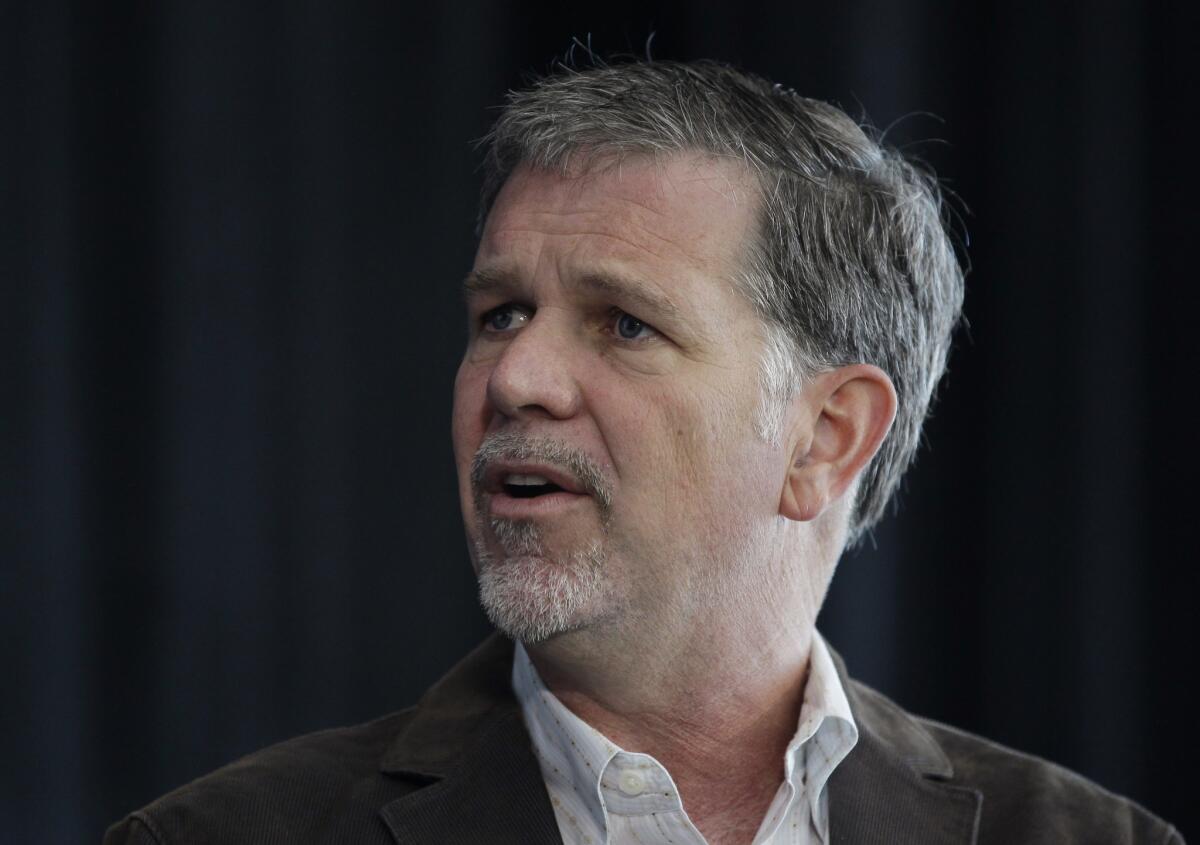

Netflix eventually struck deals directly with a handful of major ISPs, including Comcast and Verizon, to connect directly with them for a fee. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings later blasted these deals, arguing that the ISPs were forcing Netflix to pay a toll to reach its customers. To offset the power those ISPs wield, Hastings said, the FCC needs to adopt “strong net neutrality” rules that force ISPs to “provide sufficient access to their network without charge.”

There are two problems with this argument. First, as the FCC itself has acknowledged, net neutrality focuses on how “last mile” ISPs, such as Comcast, Time Warner Cable, AT&T and Verizon, handle data on their networks. Netflix’s complaint, by contrast, concerns how its data get to those networks. Such interconnection deals haven’t been covered by any of the neutrality principles or policies the FCC has adopted over the past decade.

Second, Netflix appears to be complaining about a practice that’s customary online. ISPs have long charged interconnection fees under certain circumstances, depending on the amount of traffic passing back and forth. Not allowing ISPs to charge fees for interconnection wouldn’t preserve the status quo, it would change it.

There’s no small amount of finger-pointing back and forth on this one, with some analysts suggesting that ISPs deliberately throttled Netflix and others blaming the slowdown on Netflix’ use of a transit provider whose interconnection arrangements couldn’t handle the huge increase in traffic. Regardless, Wheeler’s latest neutrality proposal (which is due to be unveiled Thursday) is expected to assert that the FCC can regulate interconnection deals, but it reportedly will require them merely to be just and reasonable. If so, ISPs should be able to continue charging interconnection fees as long as they’re fair and consistent with past practice.

While Netflix has gotten much of the attention, there’s been considerably less discussion (outside of lobbyists and activists) of zero rating, the practice of waiving data caps for featured sites or services. One example comes from T-Mobile, which exempts online music services such as Spotify and Pandora from its subscribers’ monthly data allowances, effectively making them less costly to use than Netflix, YouTube or any other data-hungry app.

In the view of some neutrality advocates, such as Public Knowledge and Engine, zero rating is a clear violation of net neutrality. They have a point; exempting selected sites and apps from data caps does put a finger on the competitive scales, interfering with the choices consumers might otherwise make.

Yet unlike stuttering Netflix feeds, waived data caps aren’t obviously evil from a consumer’s point of view. Just the opposite -- they reduce the cost of using a service. And in the case of a cheap monthly plan that provides access just to Facebook or Twitter, as Virgin Mobile does, it might be the only way someone can afford mobile access to a service he or she wants.

Nor does zero rating affect how traffic is managed on the last mile, which is the raison d’etre for neutrality rules. Instead, it affects how much ISPs charge for traffic.

Ultimately, whether zero rating is good for individual consumers isn’t the same as whether it’s good policy. On the one hand, the tactic can promote competition between ISPs, as evidenced by T-Mobile and Virgin Mobile’s offers. On the other hand, over the long run zero rating heavily favors the sites, services and apps able to strike deals with ISPs, which have no incentive to do these sorts of promotional tie-ins with companies that have no market share or buzz. That could be a huge barrier to a start-up trying to challenge the Facebooks of the world.

It’s not clear yet how the FCC will treat zero rating. Wheeler has said he wants to leave ISPs some flexibility, and some ISPs (notably AT&T) have pushed for the freedom to offer less-than-neutral arrangements that are controlled by consumers, not ISPs, sites or apps. Even if the consumer is in the driver’s seat, though, the salutary effects on ISP competition and the negative effect on new entrants appear to be the same.

The FCC isn’t scheduled to vote on the rules until Feb. 26 at the earliest. It’s a safe bet that if Wheeler’s proposal bars zero rating, consumers will have a lot more to say about that subject in the coming three weeks.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.