Why doesn’t Congress just work remotely like everyone else?

- Share via

What’s your biggest concern about Congress?

These days, you probably worry that lawmakers won’t respond quickly or boldly enough to the crisis on our hands. Squabbling between the parties allowed funding to run out for a wildly popular program to help businesses keep workers employed and paid even when they’ve slashed or even shuttered their operations. Meanwhile, plenty of other people and interest groups are crying out for federal help, including state and local governments, hospitals and public health agencies.

Some House Republicans, however, are evidently more concerned about their ability to register their opposition to the big aid packages that are making their way through Congress. And some of their colleagues are evidently more concerned about voter fraud. By House members.

The fundamental problem here is that, while the rest of the world adapts to the coronavirus pandemic by embracing remote work and digital collaboration tools, too many lawmakers remain irrationally resistant to such 21st century techniques. And the pandemic is showing the consequences of that.

On Tuesday, the Senate passed a $484-billion bill to refill the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program. The bill had been held up by Senate Democrats, who wanted to do more than just put more money into that program, which ran through the $349 billion it was initially allocated in less than two weeks. But in a compromise struck with Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin, the two sides agreed to provide $310 billion for the PPP, $50 billion for a second loan program that serves more of the small businesses not reached by the PPP, $75 billion for hospitals and $25 billion for COVID-19 testing.

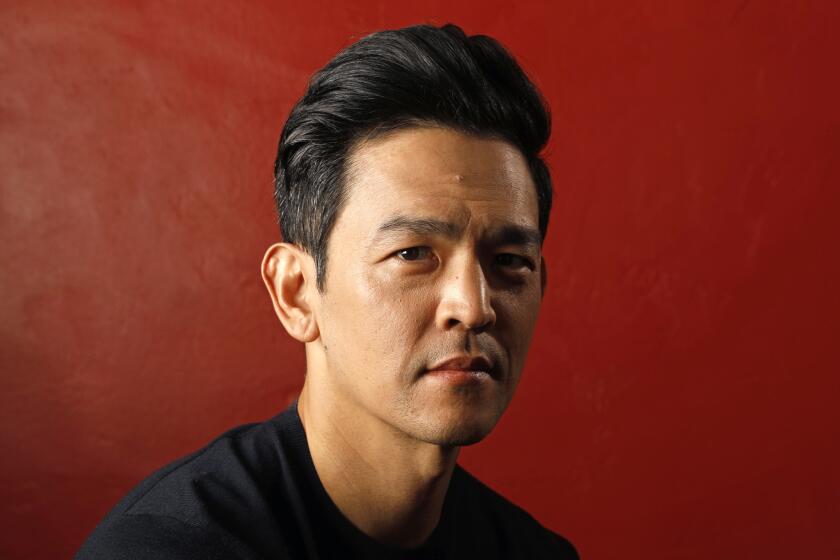

Contributor: John Cho: Coronavirus reminds Asian Americans like me that our belonging is conditional

I’ve learned that a moment always comes along to remind you that your race defines you above all else.

Notably, the Senate passed the bill by voice vote, enabling it to move the measure along while most senators remained in their home states. It was able to do so because the one senator who publicly opposed the spending, Republican Rand Paul of Kentucky, decided not to force senators to return to Washington to vote in person.

The House, by contrast, will not be able to move with such efficiency because at least one member of its Republican minority, Rep. Thomas Massie of Kentucky, insists on having a recorded vote. Massie had demanded a recorded vote on the $2-trillion coronavirus relief bill late last month too, which held up passage and forced hundreds of lawmakers back to the Capitol — where, once a quorum was achieved, they denied Massie’s request and approved the bill by voice vote.

Massie’s objection to approving big bills by voice vote is silly rather than principled. Nothing passes by voice vote unless there’s a bipartisan consensus behind it, and any lawmaker who doesn’t put his or her objections into the Congressional Record for posterity cannot credibly claim later to have opposed the bill. Registering the yeas and nays does not make a whit of difference.

But Massie is right about one thing: House members should have a way to vote remotely when it’s not safe for them to gather in the Capitol. Which is why it’s crazy for top members of his own party, including House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), to insist that all votes be conducted in person.

You might argue that it’s understandable for Republicans to be nervous about lawmakers casting ballots from a distance, given that they don’t trust ordinary Americans to vote by mail. But c’mon. There are plenty of technologies out there to help assure that a vote conducted by lawmakers in their home districts is authentic.

Worried that an aide or a lobbyist is casting the vote for the lawmaker? Then make a video feed part of the process, so the House can see who’s punching in the yea or nay. That won’t stop an aide, a member of the House leadership, a lobbyist or a close personal friend from telling the lawmaker how to vote, but nothing can prevent that under normal circumstances.

Worried about abandoning tradition? Pandemics aren’t exactly a time-honored practice in the Capitol.

Worried about someone hacking into the system? That’s a reasonable concern, but what would a hacker do? Change votes? When the House conducts a vote, each yea and nay is displayed publicly by name on the chamber’s voting boards (the Capitol’s version of a Jumbotron), so lawmakers can easily tell if their vote has been recorded correctly. A video feed of the boards could enable remote voters to do the same.

The Trump coronavirus immigration order shows he has yet to find a crisis he can’t try to exploit for his own political gain.

Massie could end up getting his way on remote voting — but not as soon as he should. After the House returns Thursday to approve the latest emergency funding bill, House Rules Committee Chairman James McGovern (D-Mass.) had planned to propose a temporary change to House rules to allow remote voting during the pandemic. But opposition from Republicans in the chamber forced McGovern to put his proposal on hold and call for a bipartisan study instead.

McGovern’s plan was more byzantine and low-tech than mine, allowing lawmakers to have a colleague in the House chamber cast votes for them according to the specific instructions they relay electronically through the House clerk. That way, every vote cast would still be cast in the House chamber.

The Constitution states that “a majority of each [chamber] shall constitute a Quorum to do Business,” but it also leaves it to each chamber to “determine the Rules of its Proceedings.” So there’s no reason the House or Senate couldn’t decide that a quorum could be established electronically, the same way that people across the country working in local governments, on corporate boards or any number of other enterprises are doing today.

The pandemic is teaching us all an important lesson: All kinds of work can be done virtually, from anywhere. Why should legislating during the pandemic be any different? And at a time like this, isn’t it better to have lawmakers in the midst of the people they represent, seeing their communities’ struggles first hand?

More to Read

Updates

9:17 a.m. April 22, 2020: This post was updated with the news that the plan for remote voting in the House was put on hold in the face of GOP opposition.

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.