Coronavirus has made it unsafe to take the California bar. So put new lawyers to work without it

- Share via

The state Supreme Court, the State Bar of California and about 9,000 recent law school graduates find themselves in a jam. It is almost the traditional time for the July bar exam, the annual hazing ritual that determines whether students have wasted three years of their lives or, instead, will be licensed and begin their legal careers.

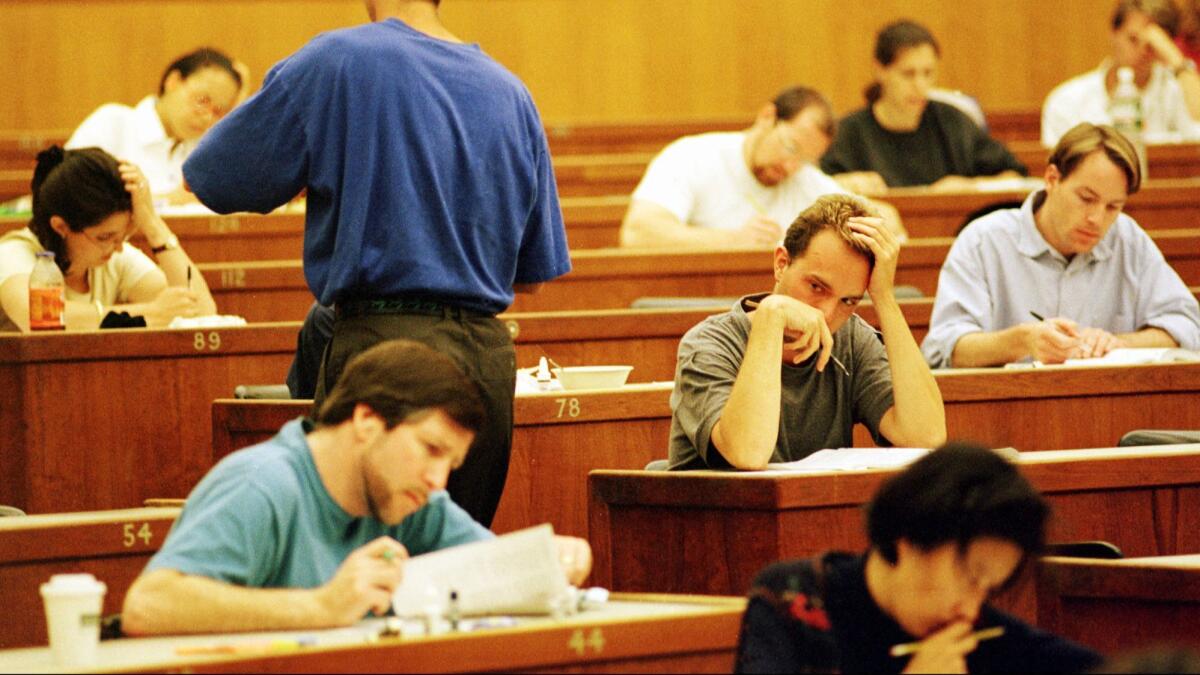

But we’re in the midst of a pandemic. There’s no way those thousands of prospective attorneys are going to be jammed into convention centers and hotel ballrooms around the state for two days of test-taking in close quarters, with face masks or without. The exam has been scrapped, so what now? Every option would heap additional headaches on the legal and testing industries and additional hardships on law graduates.

Delayed exams mean additional months in which trained lawyers can’t practice their profession, can’t earn their living and can’t begin paying back the student loans that many have amassed. Online exams pose a host of technical problems and, depending on how and when they are administered, call into question the validity of the results. October exams mean scoring won’t be completed until mid-January — too late for unsuccessful applicants to study effectively for the February do-over.

The best of the bad options is to grant provisional licenses to members of the class of 2020 right away, without tests, and allow them to practice their new profession and earn their living under the supervision of lawyers who were licensed in the old-fashioned way. Their licenses would be valid until they could take an online bar exam in October or the traditional in-person exam next year, or whenever it can next be safely administered.

Even then there are serious complications — for example, what if they had already taken the exam but failed? What if they graduated from a non-accredited law school? Should they still get temporary law licenses?

But first let’s deal with a more fundamental question that may be on the mind of any Californian who isn’t a recent law graduate: Who cares? Why should we worry that thousands more lawyers won’t be plying their trade right away? These are not, after all, recently graduated medical or nursing students whose services we badly need on the front lines of the worsening pandemic. Do we really care whether the next generation of attorneys will have to wait a few months before pleading cases or drawing up contracts?

We should care, and deeply. Millions of Californians need legal help because they have lost their jobs, or are in danger of losing their housing, or wonder about the quality of care their loved ones receive in nursing homes, or are accused of crimes, perhaps because they opened their businesses without proper clearance or because they blocked the wrong street when they protested racial inequities or police brutality.

California has lots of lawyers, but most are beyond the reach of people who need them. To make a living — while paying back their student loans and the thousands of dollars they spent on bar review courses (because law school oddly does not by itself prepare students to pass the licensing exam, any more than it leaves them ready to practice law without guidance from more experienced lawyers) — what newly minted lawyer can afford to accept what most Californians in need can afford to pay?

The class of 2020 no doubt includes many graduates with job offers at high-priced firms, but they — and the many thousands of others without such offers — presumably went to law school and prepared for the bar exam at least in part because of their passion for justice. And the justice system is in dire need of their skills.

As the State Bar of California (the licensing agency) and the state Supreme Court (which has the ultimate rule-making authority) are pondering the 2020 bar exam, it’s worth remembering that there has been no study that demonstrates that the exam does anything to protect consumers from poor-quality lawyers. Without such a study, the exam is open to the criticism that it is indeed little more than a hazing ritual — one that limits competition to practicing lawyers and supports an entire industry built on costly prep courses. Perhaps a diploma from an accredited California law school should be enough, at least in the short term.

Meanwhile, yes, grant recent law school graduates a provisional “diploma privilege” to practice without taking this year’s exam, recognizing that their graduation from an accredited law school must surely count for something. Allow them to practice under the supervision of experienced lawyers. Perhaps help them stay their loan repayments, and help with their immediate expenses, in exchange for time representing their fellow Californians who have the greatest need. And then let’s rethink the entire rationale for the bar exam.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.