Perpetrators of racist attacks are really good at shifting the blame. We can’t let them

- Share via

On Monday, two men — Julian Elie Khater of Pennsylvania and George Pierre Tanios of West Virginia — were charged with assaulting a U.S. Capitol Police officer, Brian Sicknick, with a chemical spray during the Jan. 6 insurrection. Sicknick died a day later. The arrests are the latest developments in the horrific assault on our democracy.

The images of that day continue to sicken me. But in some ways, what happened in Norman, Okla., after the vicious attack on the Capitol is just as disturbing.

On Feb. 9, Rarchar Tortorello was elected to the Norman City Council. Tortorello attended the racially charged pro-Trump protest at the Capitol but denies participating in the violence. In an interview with the Black Wall Street Times, a news site based in Tulsa, Okla., Tortorello repeated the lie that antifa followers were responsible for the attack and that the Trump supporters present were peaceful — which seems inconsistent with the insurgents chanting “Hang Mike Pence” and putting up a makeshift gallows and a noose. I doubt Sicknick would agree with Tortorello’s assessment if he were alive.

Apparently, voters in Norman who put Tortorello in office don’t care that their new councilman wanted to overturn a presidential election. Apparently, Tortorello’s support for a pro-Trump event, based entirely on lies about a rigged election and which left 140 police officers injured, did not stop Norman’s police union from endorsing him.

Last week, the city drew national attention after an announcer at a Norman High School girls’ basketball game called the players the N-word with a profanity when he saw them kneeling during the national anthem to protest racial injustice.

The racist rant was vile. The announcer, Matt Rowan, has since issued a strange apology in which he blamed his blood sugar level for his use of the racial slur. And then he said: “While the comments I made would certainly seem to indicate that I am racist, I am not, I have never considered myself to be racist, and in short cannot explain why I made these comments.”

That is a big part of the problem, isn’t it? The perpetrators of racist attacks on people of color are really good at shifting blame.

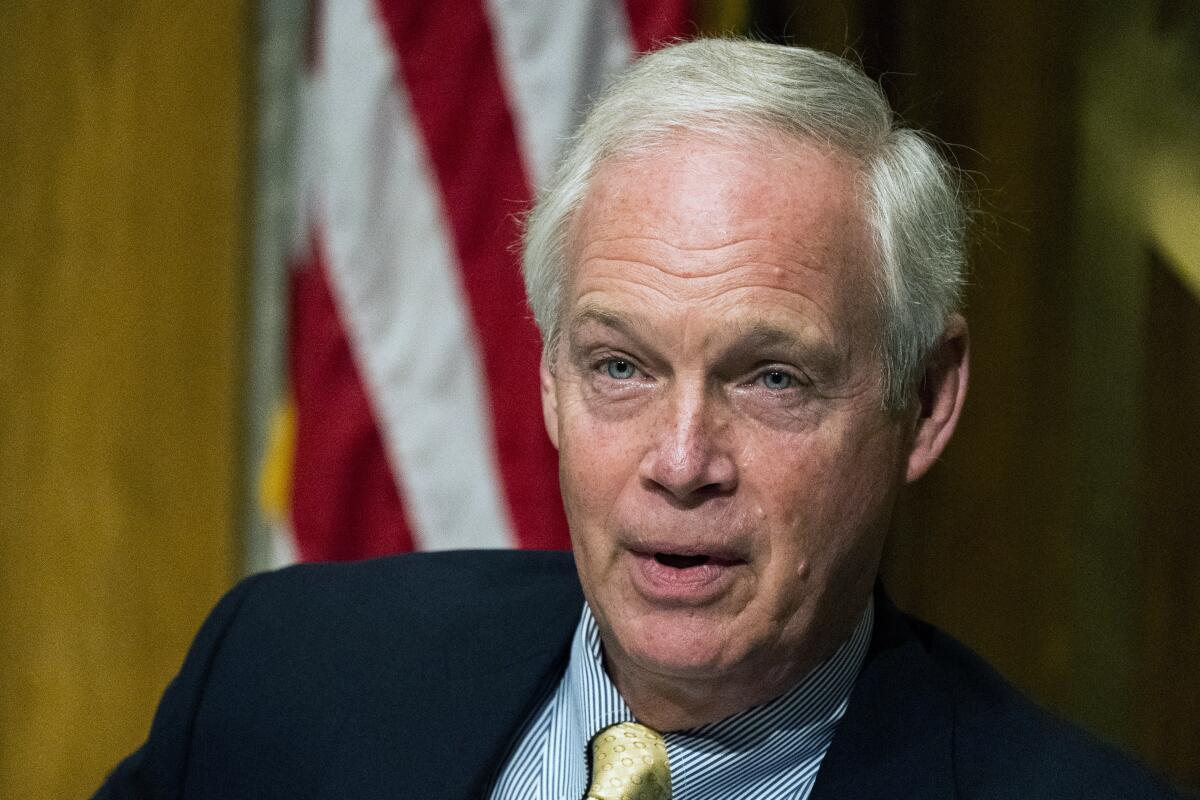

Take Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), who wrote an entire op-ed in the Wall Street Journal denying his racism after saying this about the predominantly white domestic terrorists who attacked the Capitol:

“I knew those were people that love this country, that truly respect law enforcement, would never do anything to break the law, so I wasn’t concerned.... Had the tables been turned and President Trump won the election and those were tens of thousands of Black Lives Matter and antifa protesters, I might have been a little concerned.”

See what I mean?

Anyway, just imagine what life is like for the girls on the Norman High School basketball team who live in a community that could look at the ugliness of Jan. 6 — an event saturated with racists and anti-Semitic signage — and vote for someone who had no problem being there. This is the part of the story that I find incredible. The conduct of someone like Rowan is all too believable.

Last May, a Norman police officer was under investigation after sending an email with a meme featuring the Ku Klux Klan to the entire Police Department. The year before, parts of the city were vandalized with racist and anti-Semitic slurs.

Last summer, Norman, like most of the country, was engaged in conversations about race and police funding after the death of George Floyd. In June, during a City Council meeting, Councilwoman Kate Bierman read a series of posts from a Facebook group called “Growing Up Black in Norman.”

“Growing up Black in Norman is having classmates write ‘white power’ on the chalkboards while the unknowing teachers wait outside to greet everyone,” she read.

“Growing up Black in Norman is having classmates tell you you’re an ugly Black girl every day.”

“Growing up Black in Norman is having someone tell you that if slavery were still a thing, he could rape you without consequence.”

After reading several of the posts aloud, Bierman said, “We really, really have to start listening.” And then she added: “I can’t imagine growing up in a community that … claims to be building an inclusive community and those are the kind of experiences these people have every single day.”

Norman is considered a liberal city in Oklahoma. The explicit slurs are condemned, but in Norman, and everywhere else, racial assaults are delivered in other ways.

And that’s the wrinkle in the stories of this nature that often gets overlooked: the microaggressions that people of color experience regularly. Condemning crimes, like the mass shooting in Georgia on Tuesday that killed six Asian women, is obvious. But Latinos were called rapists by a man who would become president, and Asian Americans are being targeted because of the pandemic.

This is violence, too.

How do you think Black people in Norman processed Rowan’s rant or Tortorello’s election, knowing they are in a former sundown town, an all-white city where Black people were not allowed after sunset? Where the Tulsa massacre of 1921 took place just two hours north and where mass graves are still being discovered?

Yes, the girls’ basketball team received a lot of support, from the WNBA to elected officials. But when those teenagers are driving home at night, strongly worded press releases and proclamations provide little comfort.

It’s easy to become so accustomed to the visual image of kneeling athletes that many of us don’t stop to consider what life is like for them once they stand back up, once a different news story takes center stage.

Don’t make their bravery a footnote. Their bravery is the story. This group of young women, en route to winning a state championship, expressed a demand for racial justice in a part of the country where a lot of folks didn’t want to hear them … and they made them listen anyway.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.