How can we prevent a second winter of despair with Omicron?

- Share via

Predicting future COVID waves and hospital surges is always fraught with challenges, but there are early indications from Texas, Minnesota, Britain and South Africa that the U.S. health system will experience yet another great challenge.

There is little doubt we are headed for an unprecedented COVID surge from Delta and Omicron variants combined as we head into the winter. Worse, this grim scenario means the two variants will accelerate while the U.S. healthcare workforce is already depleted and exhausted.

First Delta. In many areas of the country, less than half the population is fully vaccinated; such as only 41% in the Texas Panhandle county where Amarillo is located. Amarillo hospitals are already experiencing physician, nursing and other staff shortages as Delta cases mount; combined surges and healthcare staff shortages are occurring across the Panhandle and elsewhere in Texas.

Conditions could lead to ‘a perfect storm for overwhelming our hospital system that is already strained,’ a health official says.

This situation is likely to repeat itself among the hundreds of undervaccinated counties in the United States. From Delta alone, we are again hitting more than 1,300 deaths per day. Recent projections from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation indicate that we may reach 1 million COVID deaths in the U.S. by the end of March.

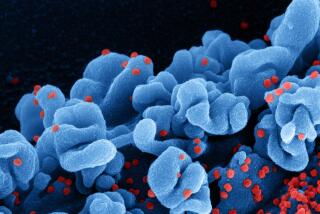

Next, the emergence of Omicron. The recent report by the U.K. Health Security Agency confirms that the high transmissibility of Omicron is not unique to the crisis in South Africa. In fact, it is projected that Omicron will eventually outpace Delta to become the dominant variant in the U.S. in the coming weeks.

Omicron’s rapid spread could destabilize our health system by infecting large numbers of healthcare providers. Here’s how this would work:

While the British government estimates the current vaccine effectiveness against Omicron around 70% to 75% against symptomatic illness after a booster, this may represent the best case scenario. Preliminary data in a preprint from the Institute of Medical Virology in Frankfurt, Germany, suggests that the levels of virus-neutralizing antibody to the Omicron variant falls sharply just a few months after boosting. The study is a small one in terms of number of subjects (and of course, it must be replicated) and there are other parts of the human immune response that could provide protection against severe disease even if neutralizing antibodies fall, but it could mean that the effect of boosting is not long lasting against Omicron infections.

The 2-1 decision by a 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals panel reverses a federal judge’s decision that had paused President Biden’s vaccine mandate.

In other words, boosting with a third dose may only provide protection against infection and symptomatic illness for short periods. This may also explain why most of the Omicron cases detected in the U.S. are among the fully vaccinated, including many who received third doses.

Additional bad news: In South Africa, we have seen large numbers of young children become very sick from Omicron. If that happens here, we could see the nightmare scenario: Hospitals having their pediatric beds, adult beds and intensive care units overwhelmed with COVID patients even as the fully vaccinated healthcare staff calls out sick because of Omicron breakthrough infections.

Adding to this situation, 18% of healthcare professionals (almost 1 in 5) have already quit or left the profession since the start of the pandemic, according to Morning Consult, and it is reasonable to expect that this trend will continue. Another study finds that up to one-half of nurses are experiencing exhaustion, depersonalization and other symptoms of professional burnout. Among the reasons for this are work-related stress, low pay, being demoralized by patients who refused vaccinations, and even taunts and threats of violence.

As Britain faces the Omicron rise, the Sunday Times of London reports that traumatized National Health Service workers are saying they won’t go back to COVID wards. Americans should anticipate this possibility in some areas of the country in January.

Both illness and attrition could reduce our healthcare workforce. Throughout the pandemic, we saw how COVID mortality sharply increased when hospital staffs and ICUs became overwhelmed.

That’s why we must take quick action to prevent instability in our health system. If there are data to support its safety and impact, an emergency fourth shot might be offered to those healthcare workers now several months out from their booster shot. Doing so could reduce the risk of breakthrough symptomatic infection and keep these individuals on the job. This is not a general recommendation for the U.S. population but rather a specific measure to protect healthcare workers during an anticipated January-February surge. Unfortunately, an Omicron-specific booster won’t be ready in time.

At the same time, we must do better at monitoring and responding to the mental health needs of our healthcare providers who remain committed to working on the front lines. Over the long term, the American Hospital Assn. and other professional organizations have outlined measures to strengthen the health system and its workforce, but we should begin identifying short-term training opportunities now for additional staff and personnel. With a new Delta-Omicron wave upon us, states and cities may need to find innovative ways to shore up depleted healthcare staffs as best they can.

Peter Hotez is a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology and microbiology and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, where he is also co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development. He is the author of “Preventing the Next Pandemic: Vaccine Diplomacy in a Time of Anti-Science.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.