Column: Who can forget Tommy Lasorda’s joy after the Dodgers won 29 years ago? ‘This team is much, much better,’ he says

- Share via

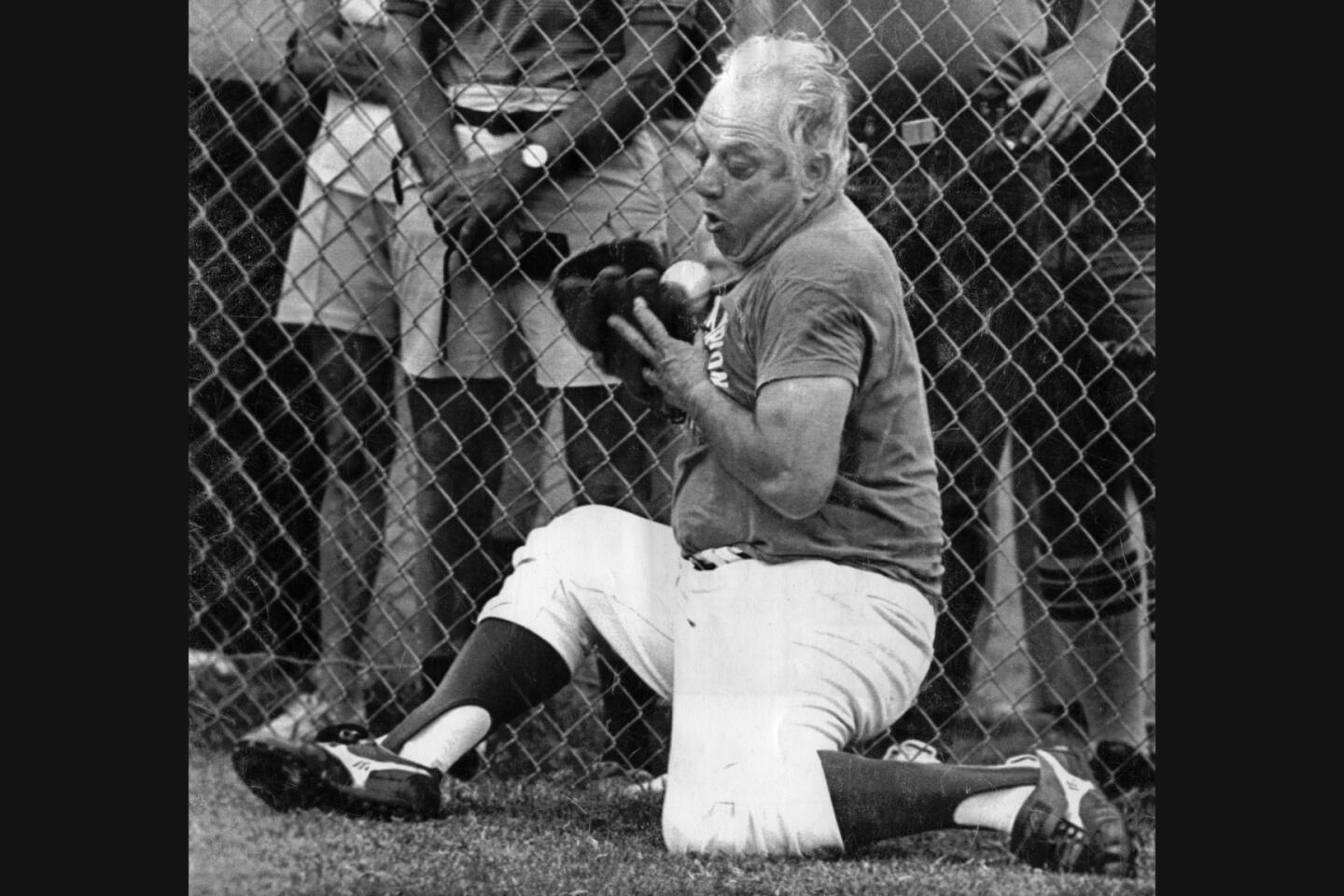

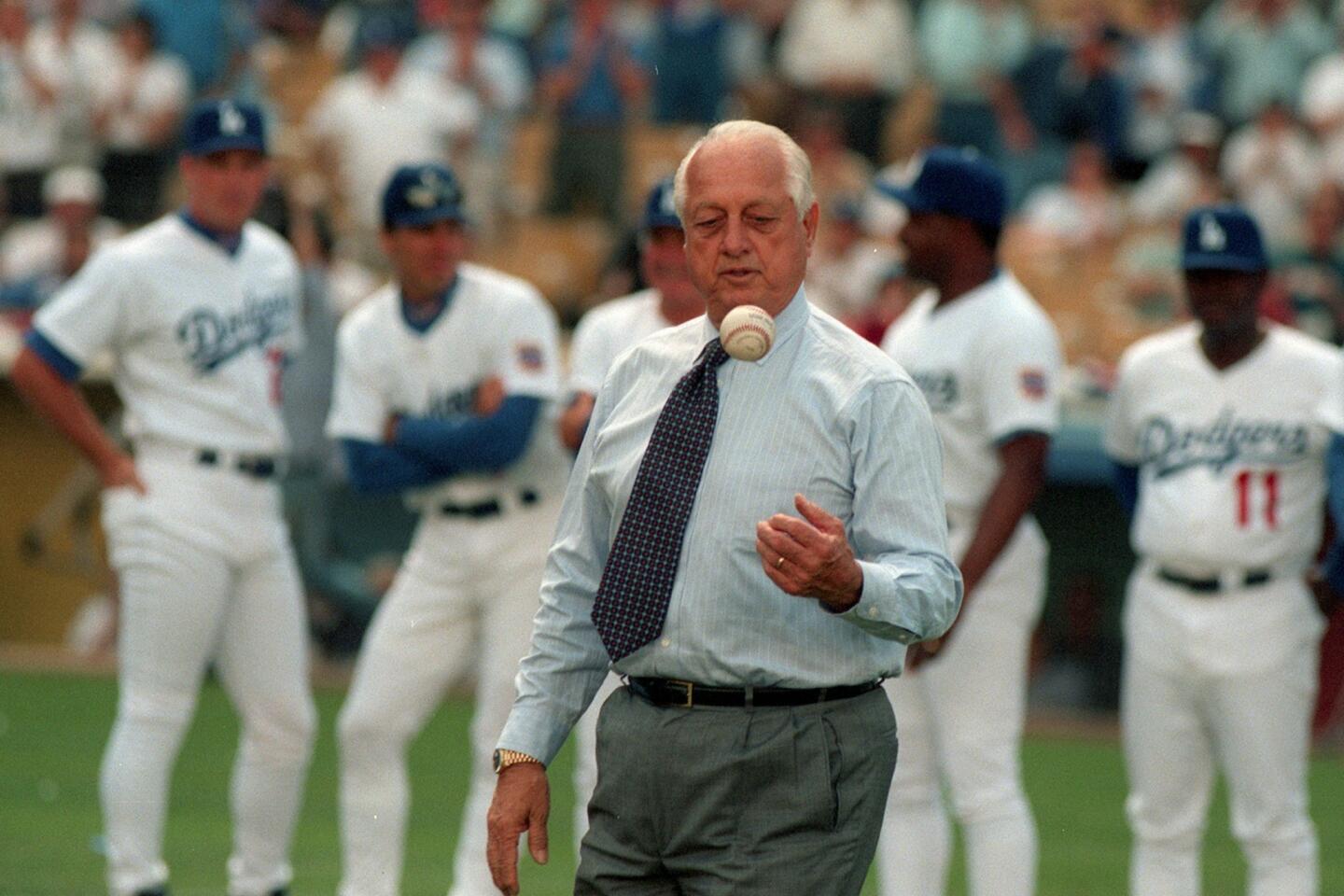

There had been a camera trained on Tommy Lasorda, no surprise to anyone who followed the Dodgers with even the slightest degree of interest.

Kirk Gibson blew off an immediate interview on the field, disappearing down the dugout steps. So NBC cut to the replays, with the two images that endure to this day.

Gibson jerked his right elbow backward, twice, as he rounded second base.

“Watch Lasorda,” said Joe Garagiola, the NBC analyst.

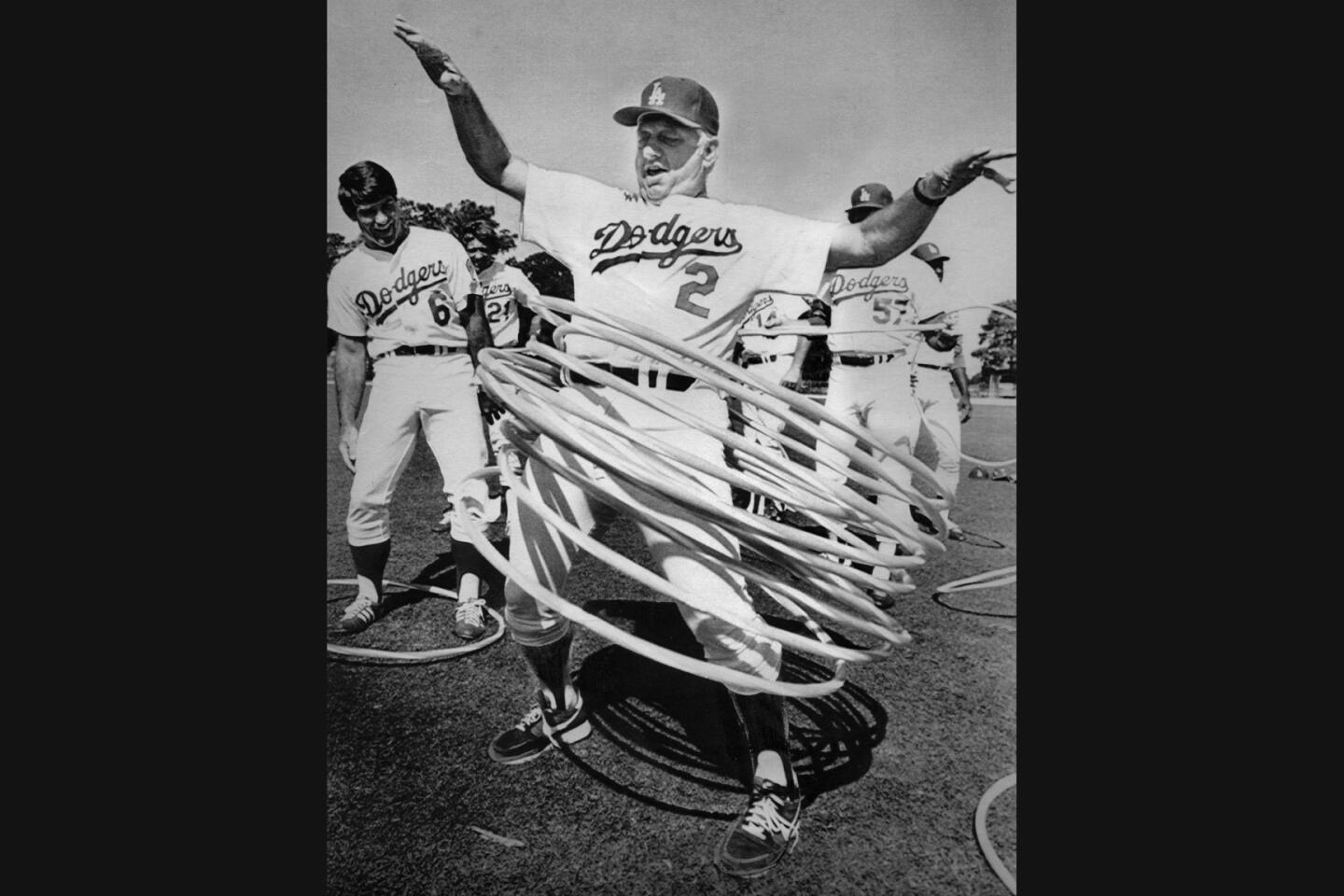

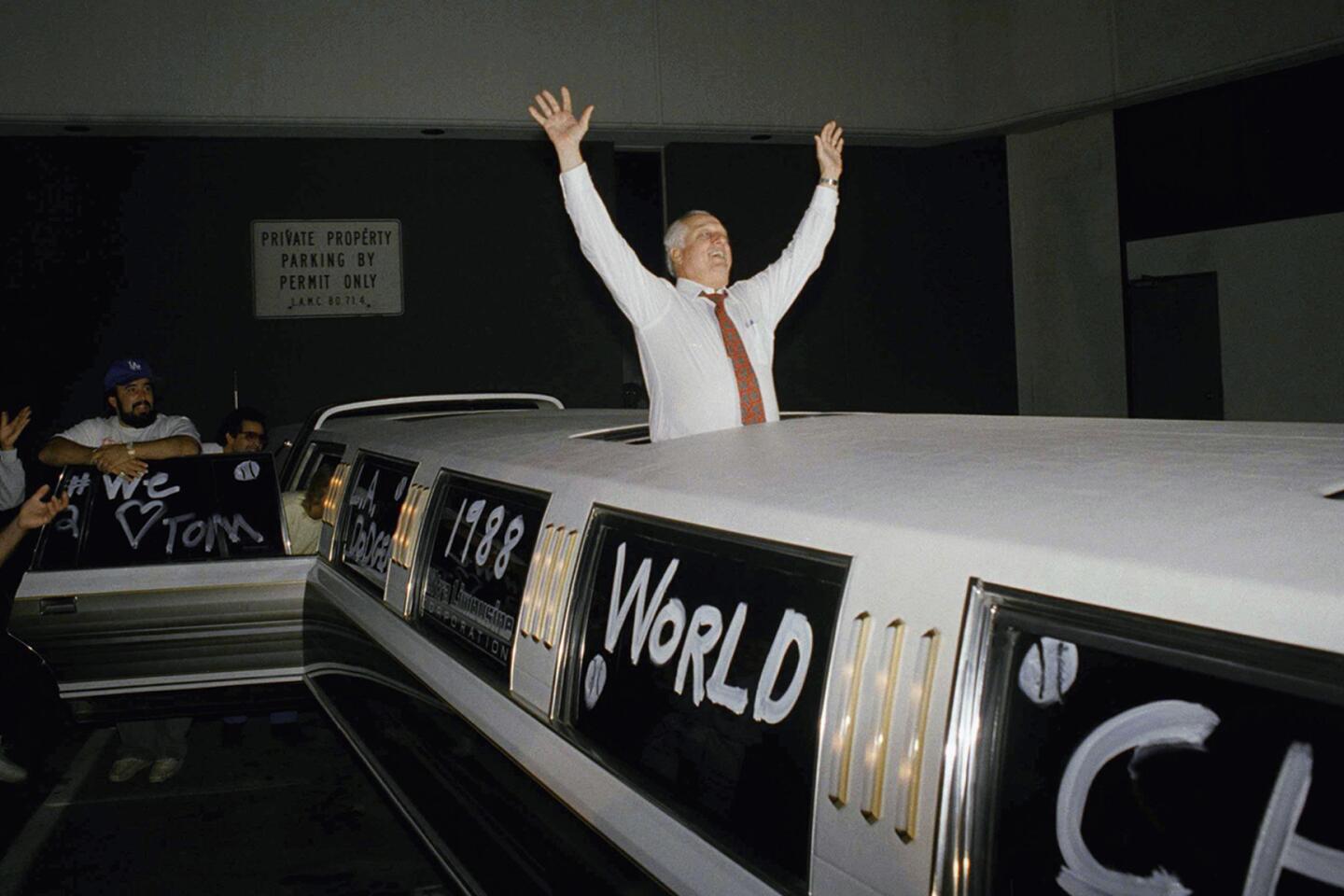

And there was Lasorda, the manager, thrusting both arms toward the sky, deliriously taking a couple steps onto the field, throwing up his arms again, hopping and skipping and huffing and puffing, his arms going up and down every couple of steps as if he were a marionette.

When Clayton Kershaw delivers the first pitch of the World Series on Tuesday, it will mark 29 years, eight days, 20 hours and about 30 minutes since the Gibson home run, that legendary exclamation point on Game 1 of the 1988 World Series. Not that Los Angeles has been counting.

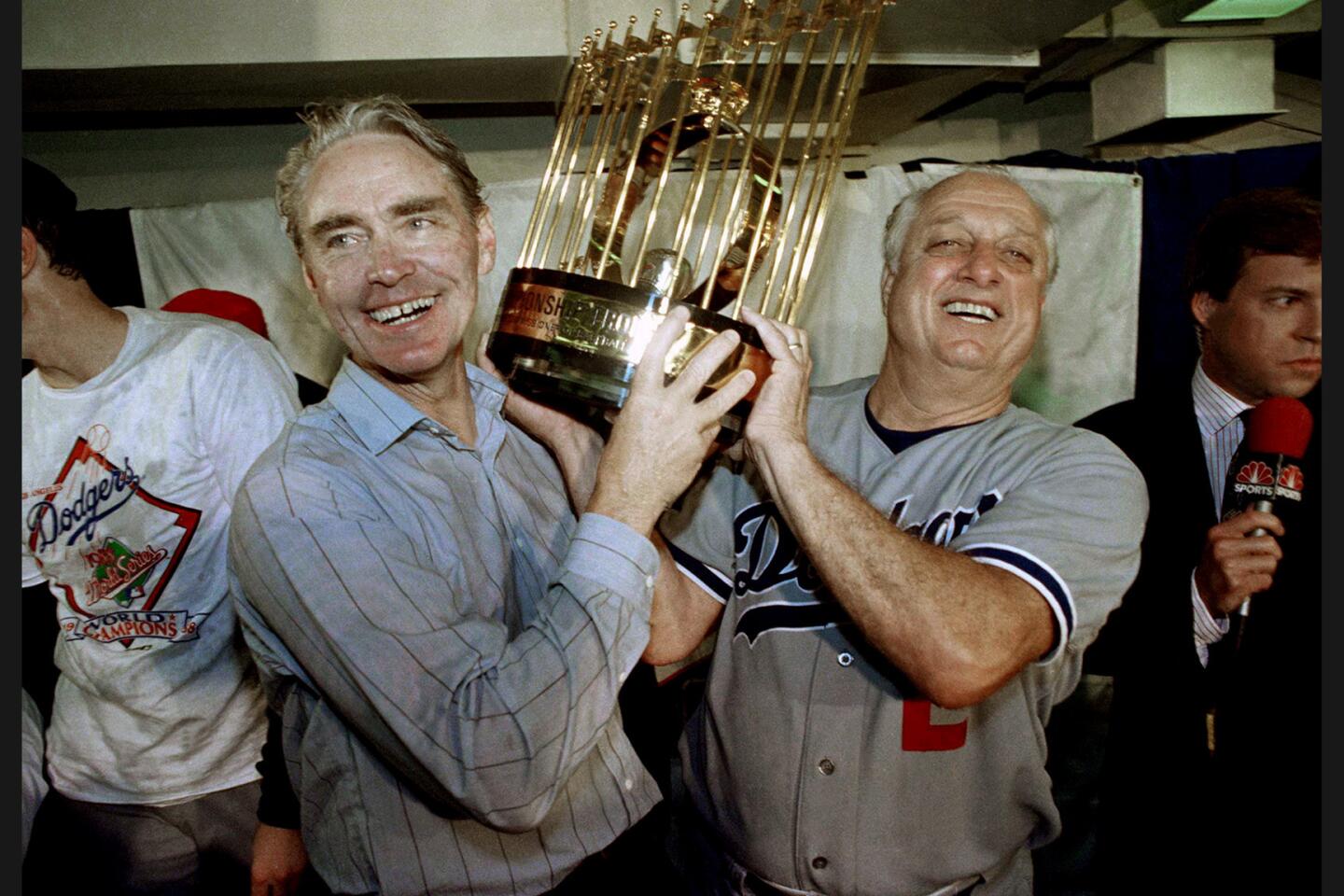

Gibson walked off the Oakland Athletics that day, the Dodgers won that World Series five days later, and the Fall Classic had gone on without the Dodgers ever since.

“It’s been a long, long time,” Lasorda said last week at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. “It’s like Chicago. They had been over 100 years. I thought our team was going to be like that.”

Until last season, the Cubs had not won the World Series since 1908. The Dodgers have not won it this year, but this team won more games in the regular season than any of its predecessors had in the six decades since the team moved from Brooklyn.

In the 1988 World Series, the Dodgers had that one at-bat from Gibson. Oakland had Jose Canseco batting third and Mark McGwire batting fifth. The Dodgers had Mickey Hatcher batting third and Orel Hershiser sprinkling magic dust.

“They scratched all year,” Lasorda said. “They believed in themselves. And we won with them.”

And the 2017 Dodgers?

Lasorda laughed.

“This team,” he said, “is much, much better.”

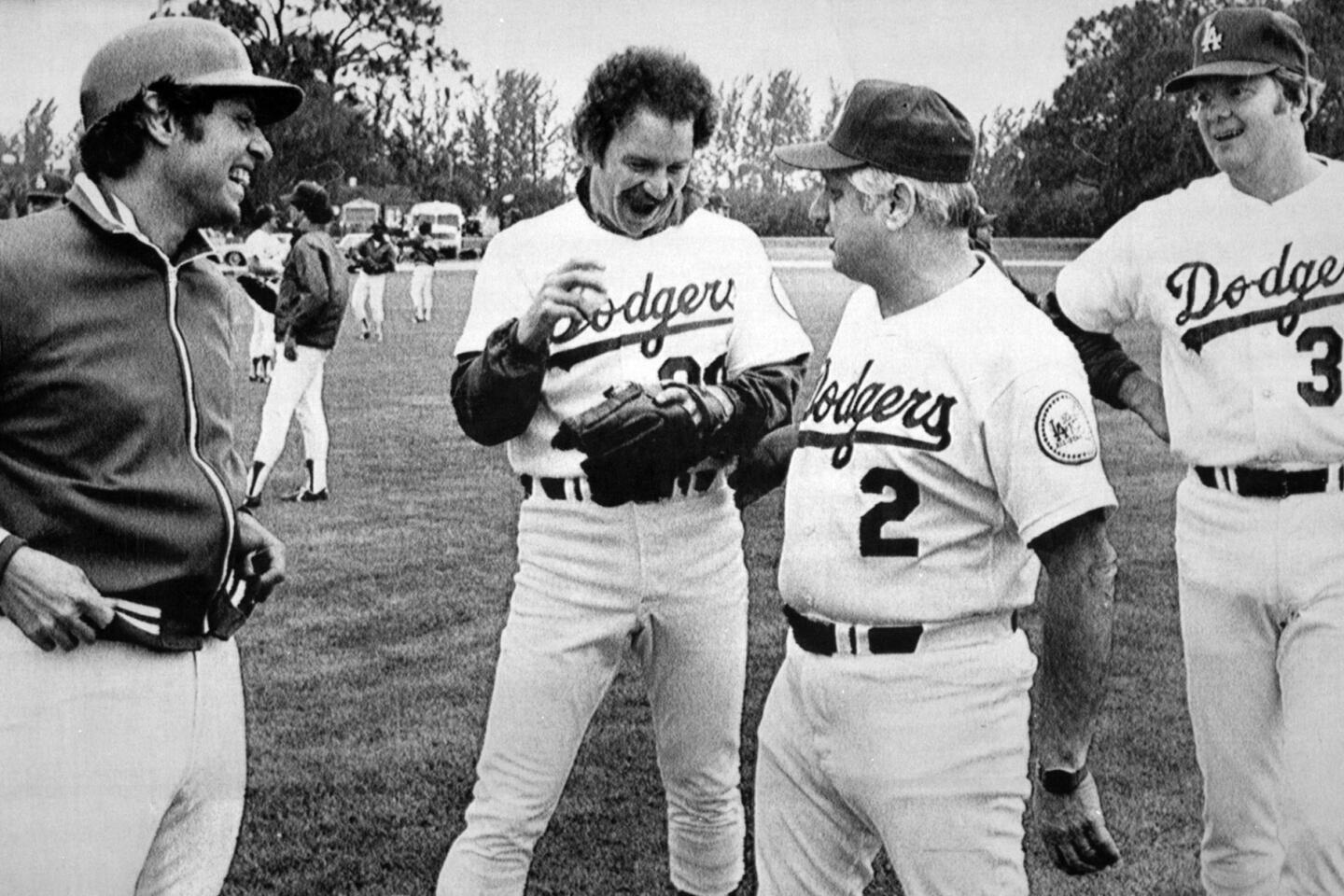

That Lasorda is part of this team feels right. That the Dodgers could find the right place for him with this team, well, that was a delicate dance for the better part of a decade.

Hershiser went on to pitch for the hated San Francisco Giants and coach for the Texas Rangers. Gibson coached for the Detroit Tigers and managed the Arizona Diamondbacks. Mike Scioscia, the catcher on the 1988 Dodgers, left the organization to manage the Angels, winning the 2002 World Series with two of his 1988 teammates — Hatcher and shortstop Alfredo Griffin — on his coaching staff.

Lasorda never left, never even entertained the thought.

“I wanted to die a Dodger,” he said. “I love the Dodgers so much.”

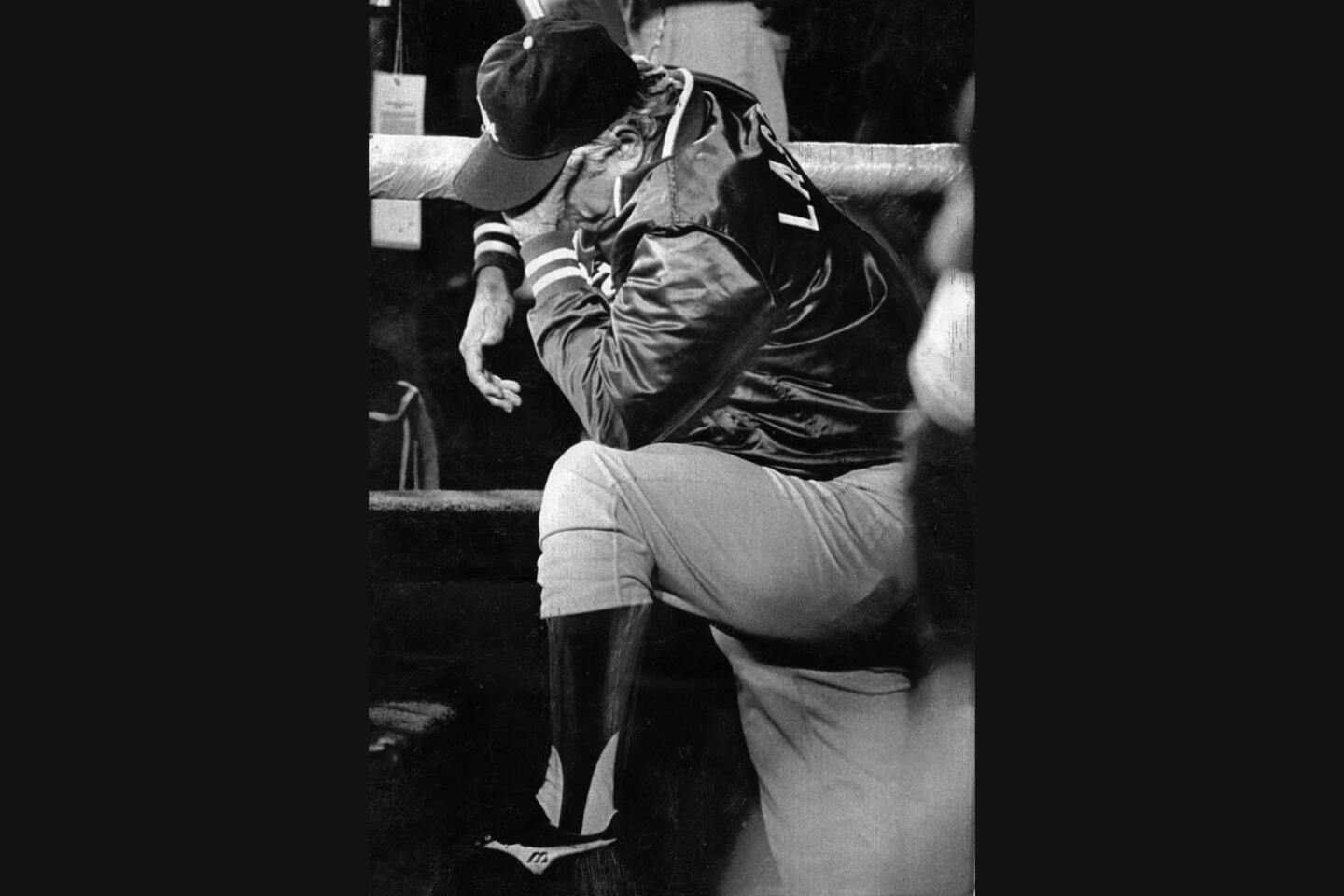

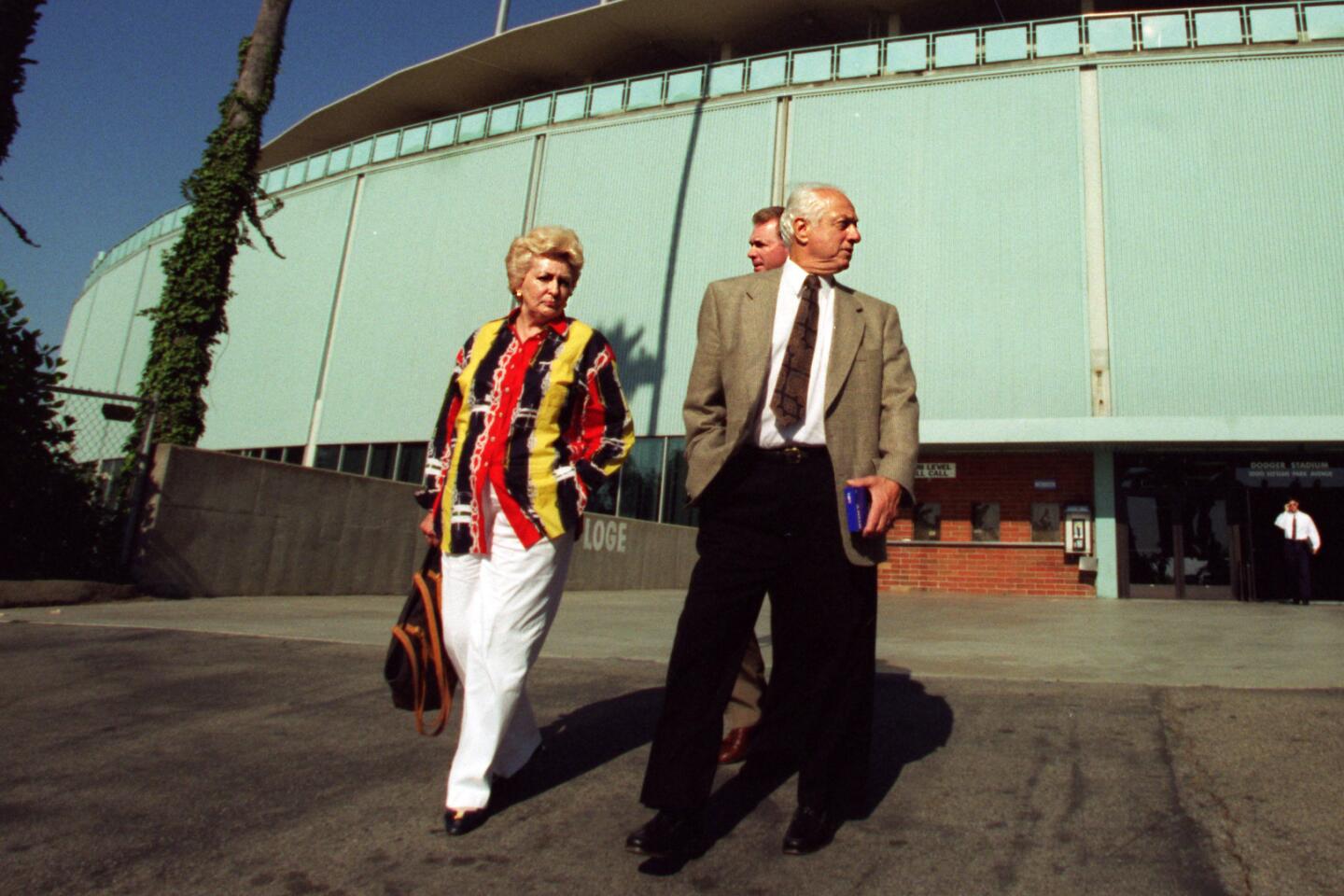

After the 1988 World Series, the Dodgers never won another postseason game under Lasorda. He was nudged into retirement in 1996, after a heart attack, and into a vaguely defined role in the front office.

In 1997, when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame, Lasorda said he liked Bobby Valentine best among all the major league managers. Bill Russell was managing the Dodgers.

In 1998, when he served as interim general manager, he traded a prospect named Paul Konerko for closer Jeff Shaw, without realizing Shaw could demand a trade at the end of the season.

In the meantime, the Dodgers had been sold, for the first time in generations. To the O’Malley family, Lasorda was family. To Rupert Murdoch and Fox, he was an employee in a corporate asset under absentee ownership, with new management eager to make its own mark.

When Frank McCourt bought the Dodgers in 2004, Lasorda lamented that he had been marginalized under Fox ownership. He was 76 by then. He no longer aspired to a big say in running the team. He just wanted to be respected and appreciated.

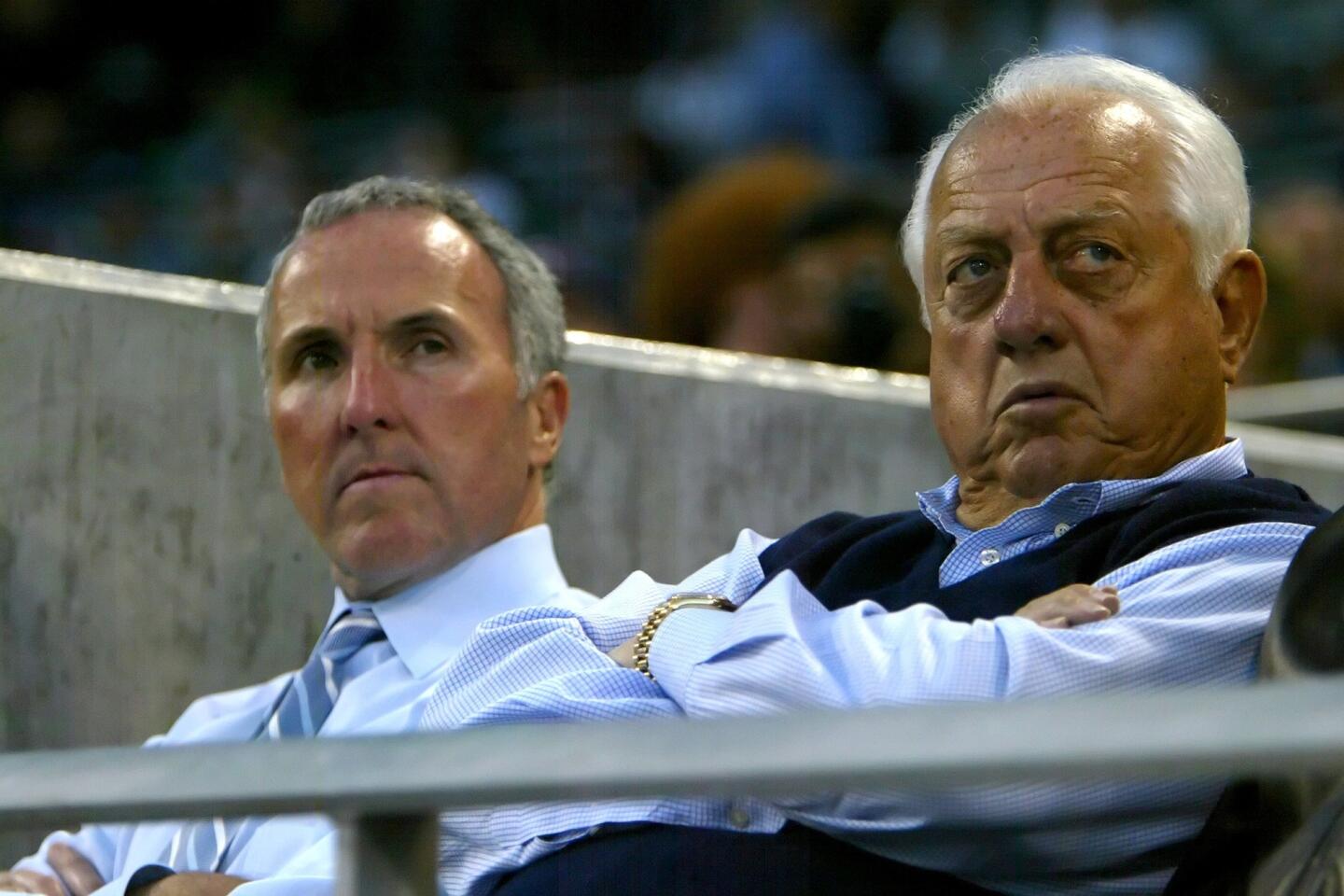

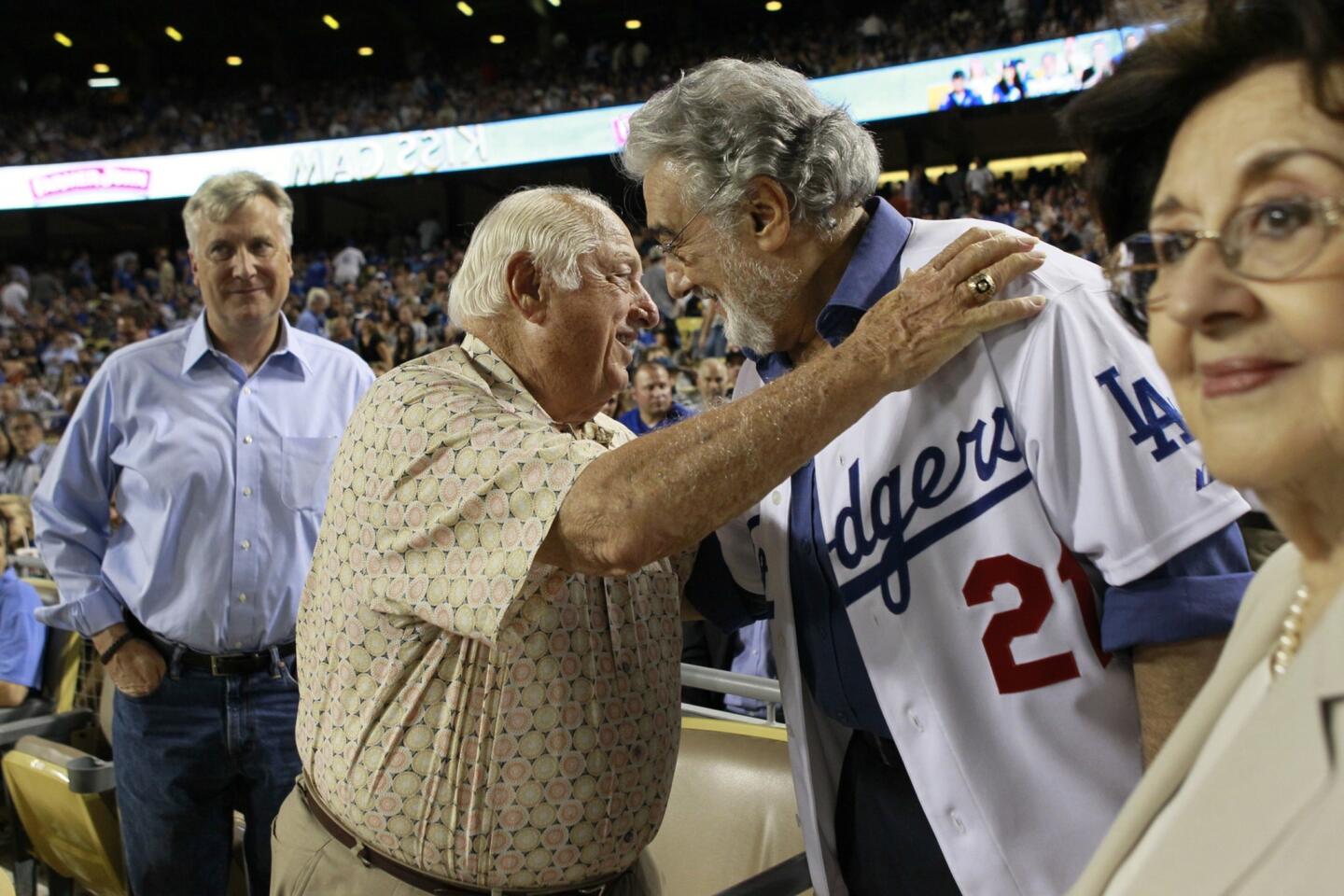

McCourt, an outsider from Boston, quickly and smartly embraced Lasorda. So did Stan Kasten, the president of the Guggenheim Baseball group that bought the team from McCourt five years ago.

Lasorda signed a ball for Kasten’s son some three decades ago, with this inscription: “You and the Dodgers are great.” Kasten said he saw Lasorda sign some memorabilia for someone recently, with the same inscription.

“All of what we know as Tommy’s demeanor and actions in life, it’s all so sincere,” Kasten said. “He thinks this, 24-7. In every fiber of his being, there has never been anyone, anywhere that can equal that part of his personality.”

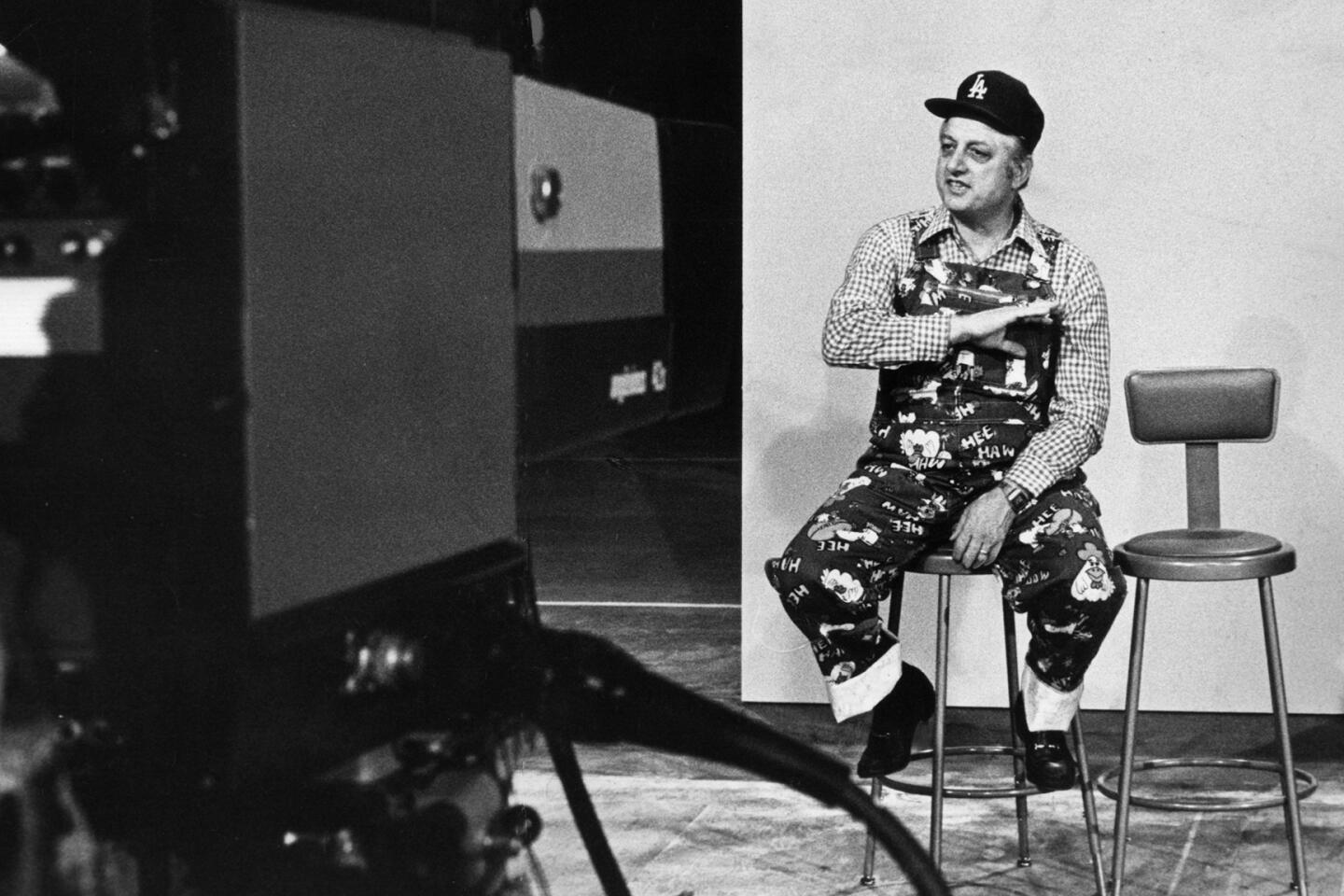

Lasorda’s role is most often described as ambassador, and that fits. So does mascot, but not in a disparaging way. He represents the team and makes fans smile.

He preaches the Dodgers gospel far and wide. He signs autographs for countless hours during spring training, lends his likeness to bobblehead dolls, spins stories of his seven decades in baseball, poses for selfies with fans, sits in the owners’ box more than the owners.

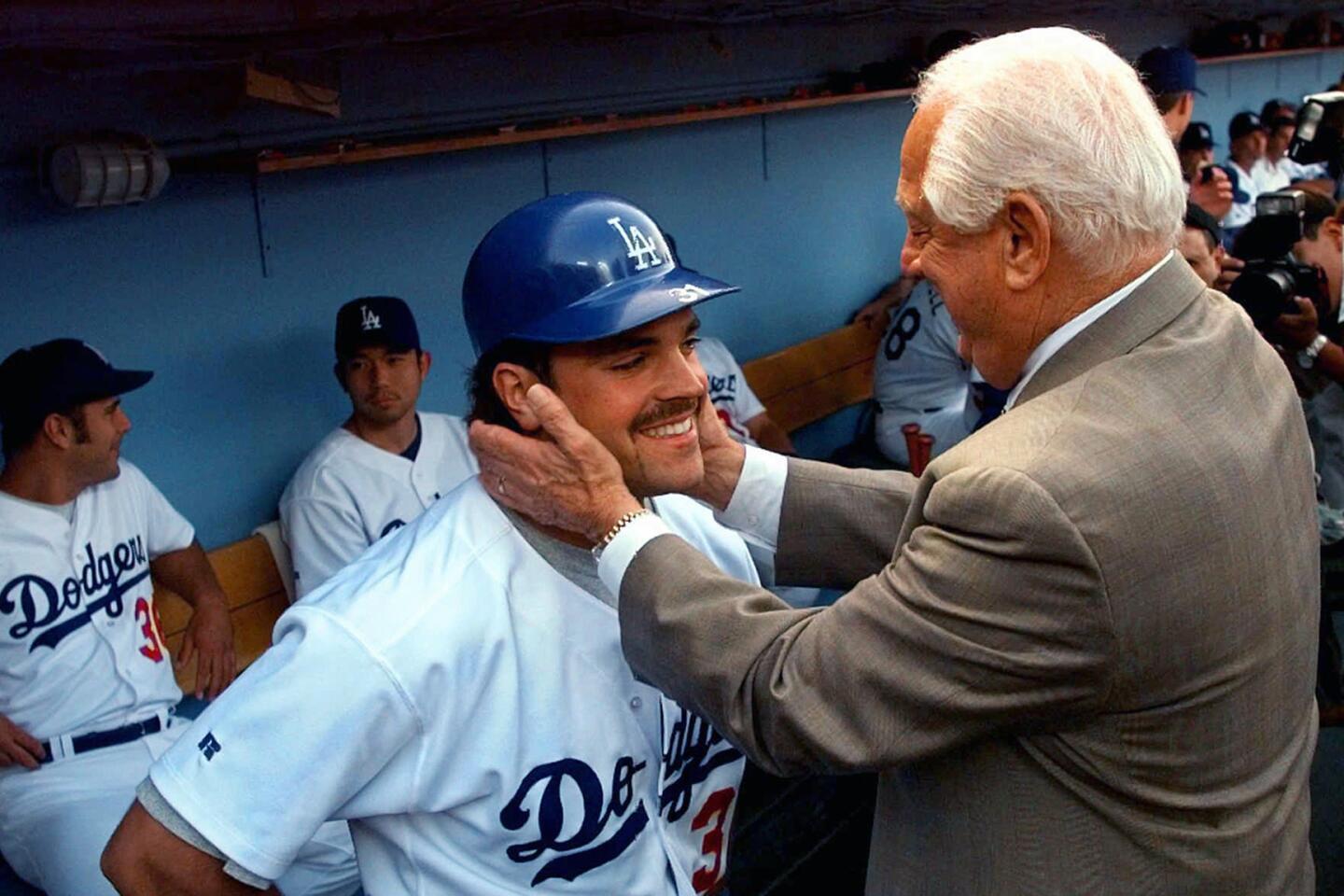

When Kershaw signed his first contract, at 18, he and his mother got to meet Lasorda.

“That was pretty cool,” Kershaw said.

When Kenley Jansen participated in his first spring training, as a 17-year-old catcher, Lasorda needled him about needing to hit better if he wanted to avoid returning home and cutting sugar cane in Curacao. (Not true, but pitching came later.)

When Dave Roberts participated in his first spring training with the Dodgers, as a 29-year-old outfielder, Lasorda took over his session with the hitting coach, advising Roberts to hit down on the ball and sticking around for another two hours to make sure he did.

“Called me ‘The Okinawa Kid,’ ” said Roberts, who was born in Okinawa, Japan. “Until I became manager, I don’t think he knew my name.”

When Alex Anthopoulos joined the Dodgers front office last year, he joined Lasorda for dinner one night. Or, at least, he waited at the table while Lasorda was repeatedly stopped for autographs and pictures.

“It was like sitting with the Godfather,” Anthopoulos said. “Everybody knows who he is.”

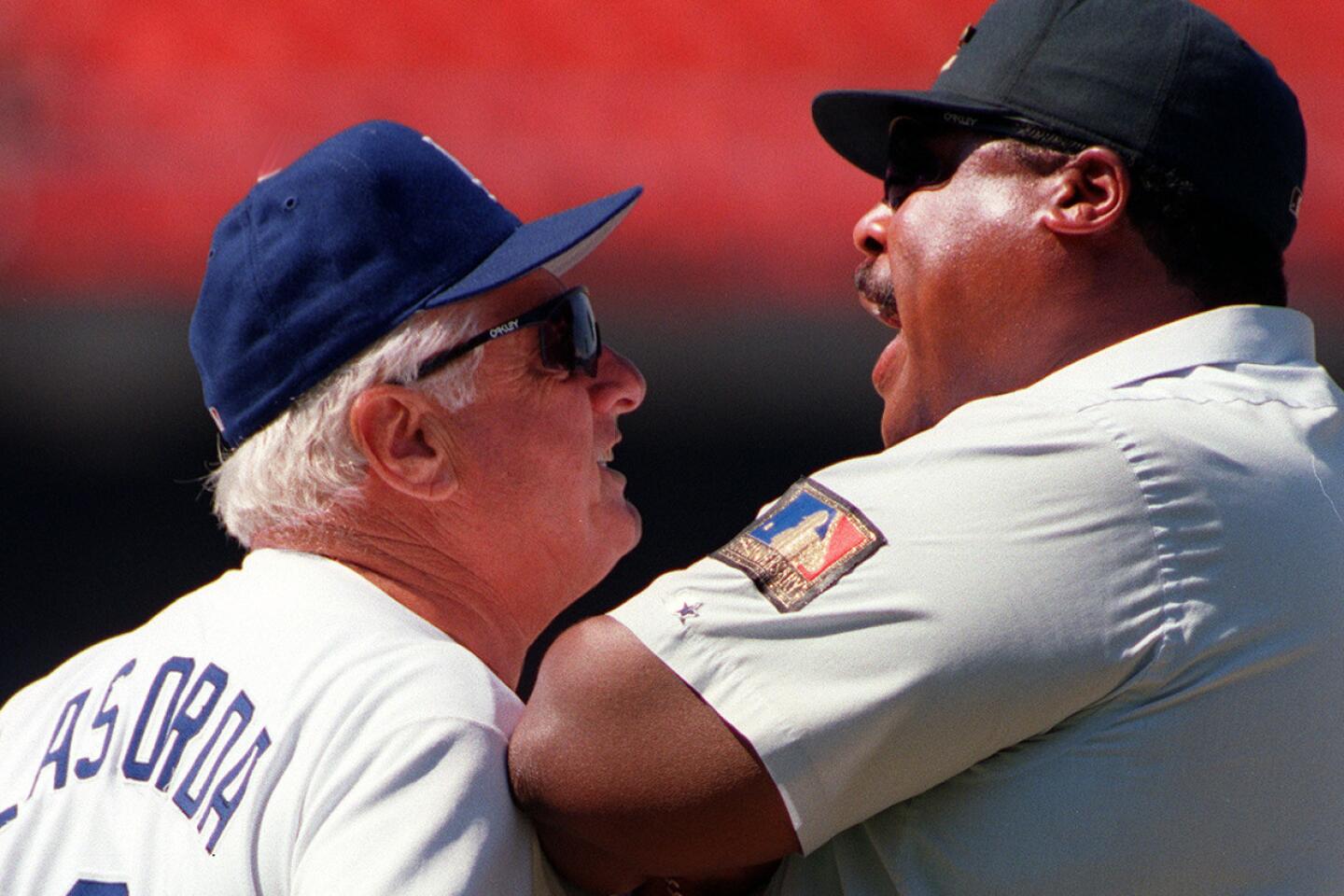

That has been true since Lasorda managed, when he was the face of the team. His office was a social club. Lasorda might have interrupted an interview to say hello to Frank Sinatra, or to invite his players to come on in for the latest catered pasta.

Lasorda’s style of managing never would fly today. The Dodgers clubhouse is much larger and the manager’s office much smaller. The players are the stars, in Los Angeles and elsewhere. The front-office executives are celebrities, a trend accelerated by the rise of fantasy sports and the accessibility of analytics. The manager is a middle manager, a corporate spokesman.

Front-office types walking into the clubhouse to present data and offer advice to players? Back in the day, that was heresy.

“I never had that happen in my 20 years,” Lasorda said. “But they’re part of the team. They’re part of the winning. They’re part of the losing. These guys take an interest that’s a little unusual. They go down every day and talk to the guys. It’s OK. It’s all right.

“Just so they win. That’s the main thing.”

They win. Just in time, perhaps.

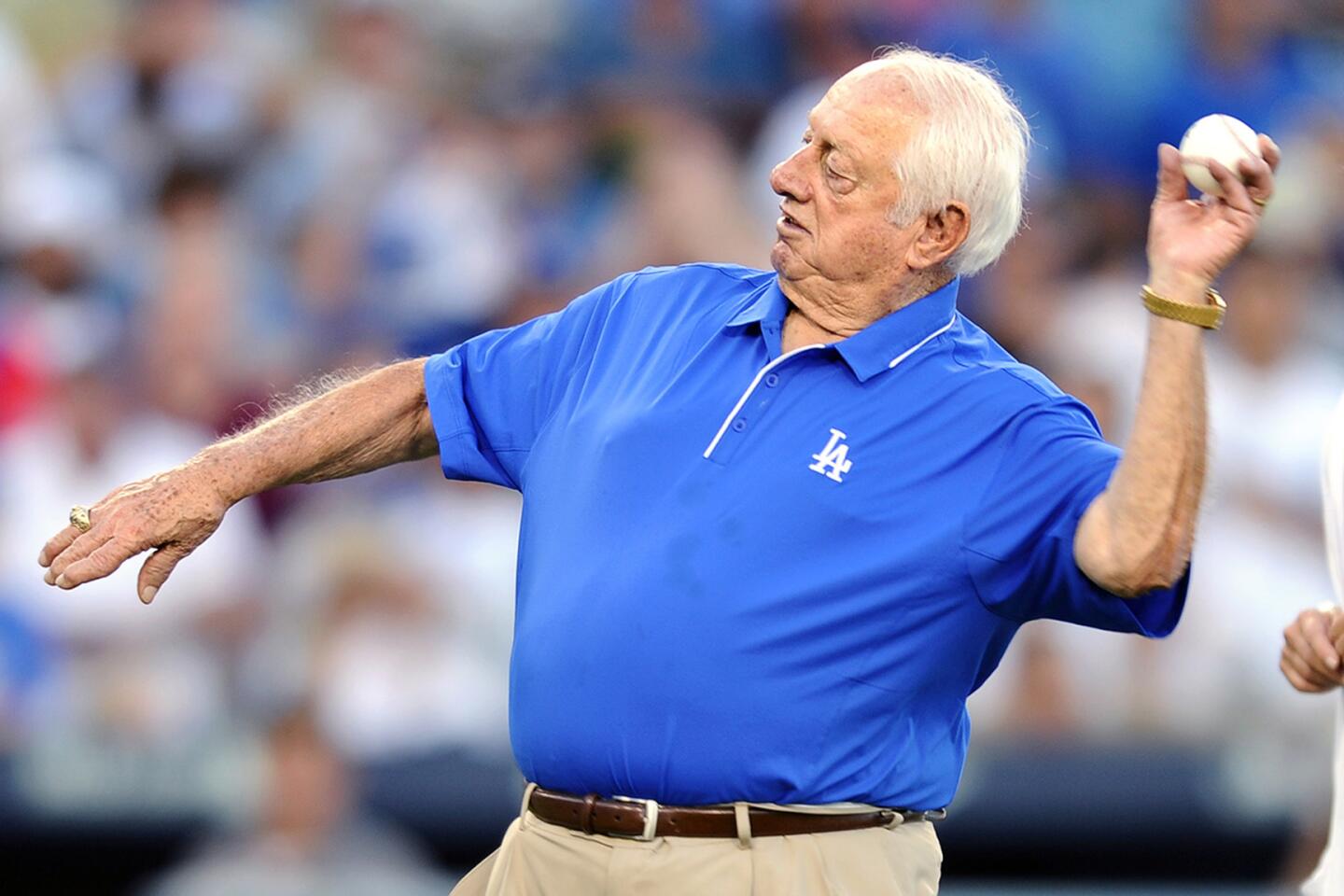

Lasorda turned 90 last month. He is a blue lion in winter.

He had a pacemaker installed in May. He sometimes uses a motorized wheelchair to navigate Dodger Stadium.

The lines he has delivered for decades — wanting to see one more World Series championship before the Big Dodger in the Sky calls him home, hoping the team schedule can be affixed to his tombstone so cemetery visitors can see whether the Dodgers are playing at home that night — no longer ring so funny.

The World Series opens Tuesday, at the ballpark Lasorda calls “Blue Heaven on Earth.” If the Dodgers win, Lasorda could ride in one more parade.

“I hope so. I think so. I believe so,” Lasorda said. “I believe we are going to do it.”

He paused, just long enough to command attention and anticipation from his listener.

He might not talk as loudly as he used to. He might not walk as fast.

The twinkle in his eye is every bit as defiant as ever.

“We’d better do it,” Lasorda said.

The Los Angeles Dodgers in the 2017 World Series

Follow Bill Shaikin on Twitter @BillShaikin

ALSO:

Dodgers vs. Astros: How the teams match up for the World Series

Dodgers leave outfielder Curtis Granderson off World Series roster

Roberts vs. Hinch: Friends square off as managers in the World Series

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.