Can college football be played in 2020? Power Five commissioners seek a suitable plan

- Share via

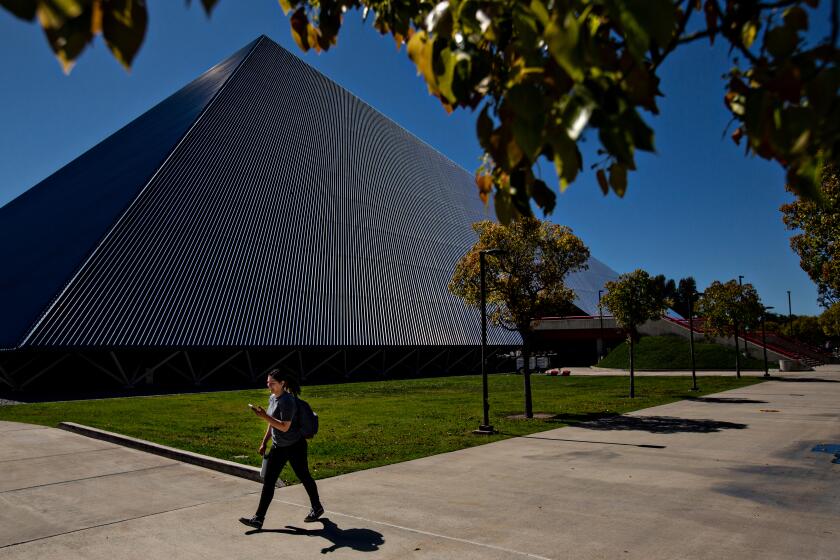

It’s September in Seattle and hundreds of boats idle on Lake Washington outside Husky Stadium for “Sailgating” as the purple and gold prepare to host the Michigan Wolverines. In Arlington, Texas, tens of thousands of fans pour through the turnstiles of AT&T Stadium to watch blue-blood programs USC and Alabama kick off the season in prime time.

The next weekend, in Eugene, “Bucknuts” wearing scarlet and gray converge on Autzen Stadium for Ohio State-Oregon, a possible playoff preview.

Through it all, glasses clink, hands slap, voices raise, drums beat, trumpets sing.

Now, listen to Kirk Herbstreit, the man who surely would be calling several of those games for a national audience, say that he will be “shocked” if there is college football in 2020.

“I’ll be so surprised if that happens,” Herbstreit said on ESPN Radio, sounding an alarm.

“Just because, from what I understand, you’re 12 to 18 months from a vaccine. I don’t know how you let these guys go into locker rooms and let stadiums be filled up and how you can play ball. I just don’t know how you can do it with the optics of it.”

The NCAA Division I Council group will meet as originally planned in late April to push legislation forward on name-image-likeness issue despite the coronavirus pandemic.

Herbstreit is no public health official or epidemiologist, but his words cut deep from coast to coast. For many sports fans, no matter how soon the NBA and NHL restart their seasons or Major League Baseball stages its opening day, the nation will have only come back to life after the COVID-19 pandemic when helmets crash on crisp fall Saturdays.

Reached this week, Pac-12 Commissioner Larry Scott acknowledged Herbstreit’s grim prediction could come true. Scott also theorized what it would mean if it didn’t.

“It does in a way reinforce how important sports are to the American psyche,” Scott said. “There’s a real sense of loss that people have, that sense of connection, and I do think seeing college football games being played in stadia on our campuses will be an important marker and litmus test as to whether we’re getting back some sense of normalcy as a country.”

While the NCAA had the power to decide whether the Division I men’s basketball tournament and the other winter and spring championships would be held, in the Football Bowl Subdivision, the decisions will lie with the conferences and, in the case of the postseason, the College Football Playoff and bowls.

The NCAA would make the call on the Football Championship Subdivision, Division II and Division III, but all it can do with FBS is offer a recommendation at the appropriate time, an NCAA spokesman said.

That puts Scott and the other Power Five conference commissioners in a position to chart a course.

Scott said he has been on daily phone calls with that group, which is only beginning to tackle the football issue. Until Monday, when the Pac-12 announced pandemic guidelines for its schools and suspended team activities until May 31 and the NCAA voted to allow an extra year of eligibility for spring sport athletes, Scott said those urgent matters took precedence over football.

Scott said the Pac-12 has formed a committee of 12 football “experts,” one from each school, to analyze the situation from all angles.

The May 31 date could hold significance for the football issue, too. Scott said he would like to be able to make decisions about the start of the season by then.

“What would summer need to look like and how many weeks of training camp would we need to have so that student-athletes could safely start a football season?” Scott asked. “Keep in mind, we’ve got programs that didn’t get a chance to have spring football, and in our league, at Washington State and Colorado, Nick Rolovich and Karl Dorrell are new coaches that didn’t get to have their spring practice.

“In an ideal world, we would have a longer than normal training camp and ramp-up period to somehow accommodate for the fact that we missed spring.”

Notre Dame coach Brian Kelly this week responded to Herbstreit’s comments by saying that players would need to be back together on campus by July 1 to start the season on time.

“We have to keep in mind that student-athletes and college sports are part of a broader ecosystem on our campuses and higher education,” Scott said.

At a minimum, two things would have to occur for teams to get up and running: Universities would have to reopen to students, and social distancing requirements would have to be lessened to the point 100-plus players and staff could congregate for practice.

To even think of staging games with fans in attendance would mean that new cases of COVID-19 had dwindled to a trickle at least — and that the virus did not return in fall’s cooler temperatures.

“There’s been broad acknowledgment that there could be a second wave in the fall,” NCAA Division I Council chair M. Grace Calhoun said.

Canceling the college football season would be a decision that would financially cripple many athletic departments. For administrators, it does not get much weightier than that.

Schools will have discretion in deciding whether to continue scholarships for returning seniors, but mid-majors will face harder financial decisions.

According to a survey of more than 100 FBS athletic directors released Thursday by Lead1, an organization that represents their interests, 35% are forecasting a revenue decrease of at least 30% in 2020-21, with football the key variable.

Scott is hopeful that early social distancing in states such as Washington and California will give Pac-12 programs a chance to return to campus earlier than in other parts of the country.

“I’m cautious to think that way,” Scott said. “If you start understanding that our student-athletes and our students are from all over the country, let alone the world, and our alumni that attend our games are from all over the country, I’m not inclined to think that regionally college football is able to have a staggered start. I think it’s more likely either we’re ready as a nation or we’re not.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.