Stained by permanent ink

- Share via

DETROIT — There’s a new chapter being written in the Cult of Celebrity handbook -- one with no spoiled athletes, playgirl heiresses or adulterous movie stars involved.

It’s taking place in the unlikely world of newspapers, a field with so few national superstars that it is usually hard-pressed to come up with a decent scandal. True, there were the Stephen Glass and Jayson Blair affairs. But they were just promising up-and-comers, unknown to the general public until they went bad.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. April 23, 2005 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Saturday April 23, 2005 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 38 words Type of Material: Correction

Mitch Albom -- An article in Friday’s Calendar section about Detroit Free Press writer Mitch Albom identified NBA players Mateen Cleaves and Jason Richardson as graduates of Michigan State University. They attended the university, but did not graduate.

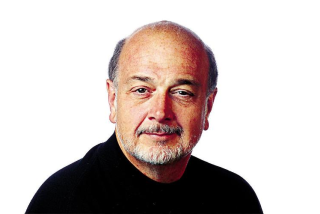

This one involves an honest-to-goodness luminary: Mitch Albom.

He’s won every award that sports journalism has to offer. But what elevates Albom’s indiscretion into the realm of celebrity scandal is that his fame goes way beyond the world of newspapers. This is the guy who wrote “Tuesdays With Morrie” and “The Five People You Meet in Heaven,” both inspirational mega-sellers. He’s a playwright, a syndicated radio host and a regular on ESPN’s “The Sports Reporters.”

And he’s one of Oprah’s pals.

So when parts of one of Albom’s columns turned out to be fictional, people took notice.

First, a bit about his transgression.

Because of the deadline quirks at his paper, the Detroit Free Press, Albom files his Sunday general interest column two days early -- on Friday. That presented a dilemma when Michigan State University was scheduled to play in the NCAA men’s basketball semifinals on Saturday night, April 2 in St. Louis. Albom’s column dealt with two MSU grads -- Mateen Cleaves and Jason Richardson, both now pro basketball players -- who were going to the tournament to watch their old college team play.

Albom’s solution? He disregarded the fact that he was writing 24 hours before the game.

“They sat in the stands, in their MSU clothing, and rooted on their alma mater,” Albom wrote. He went on to give readers details on how they had flown in for the game. “Richardson, who earns millions, flew by private plane. Cleaves, who’s on his fourth team in five years, bought a ticket and flew commercial.”

But in one of those twists that turn mundane stories into legends, Cleaves and Richardson changed their minds. Neither one attended the game, rendering Albom’s touching story a piece of fiction.

The story wasn’t malicious or libelous, but it was a fabrication, one that was syndicated to scores of newspapers. (The Free Press is a Knight Ridder publication, but the column is distributed by Tribune Media Services., part of Tribune Co., which owns the Los Angeles Times.) The Free Press published apologies by Albom and Free Press Editor and Publisher Carole Leigh Hutton.

“There are some cardinal rules in this business, and one of them is you don’t write about stuff in anticipation of it happening,” says Neal Shine, the retired publisher of the Free Press who, as senior managing editor, helped hire Albom away from the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel in 1985. “It’s that simple.”

Maybe it’s simple for someone like Shine, who teaches a journalism ethics course at Oakland University in suburban Detroit. But for the other side of journalism, the side concerned with the ever-shrinking bottom line, this is a much stickier situation.

“Albom is really the only recognizable name they [the Free Press] have,” says Jack Lessenberry, a journalism professor at Wayne State University who writes “a column critical of the media” for the Metro Times, an alternative weekly in Detroit. “I think they will bend over backwards for marketing reasons to not fire him unless they absolutely have to.”

Firing, if it comes to that, is a long way off. Hutton has turned loose a team of investigative reporters to determine if this was an isolated incident or if it is part of a broader pattern. She says she doesn’t know when their work will be completed. Similarly, the paper is conducting an internal review of the editing procedures that permitted Albom’s column to be read by at least three editors and still appear in the paper unchanged.

In the meantime, Albom’s column has been suspended and he is on a paid leave of absence.

The very notion that anything might come between the paper and its franchise writer must be a nightmarish prospect for the Free Press, which has seen its circulation drop about 35% in the last decade.

Albom is a demigod here. Mention that Albom will be at a benefit and you’re guaranteed a sellout. He’s on the radio 15 hours a week, reminding listeners that the only place they can read him is in the Free Press. In the wake of the scandal, reader mail has run 4-to-1 in his favor.

“I urge you to accept Mitch’s apology and leave it at that,” wrote one impassioned reader. “If any action is taken that is heavy-handed or harsh, I will never buy a Free Press again. Mitch is the best -- literally. You owe him -- literally.”

So what’s a paper to do? Stand on principle or cut the guy a break?

*

Getting into his head

How could this happen? How could a smart and seasoned columnist do something so clumsy and so blatant? And just as troubling, how could editors let it happen?

Albom didn’t respond to phone calls or e-mails asking that he comment for this story.

The slack editing, though, is easier to pinpoint.

At an April 7 staff meeting, a Free Press reporter, originally a copy editor, said he had been told to keep hands off Albom’s columns when he joined the paper. Spell-check them. Make sure there are no glaring errors. But if there were any substantive questions, don’t ever approach Albom. Refer them to his editor and then forget it.

The message was clear. Albom was a golden boy who was accountable to no one but himself.

“There were the Mitch rules and then there were the rules for everybody else,” says Terry Foster, who wrote at the Free Press back in the 1980s and is now a columnist for the Detroit News. “Mitch meant more to the Free Press than anybody else, which created lots of resentment from other reporters.”

Foster said he had larger questions about Albom’s journalistic integrity.

“Sportswriters talk about it all the time,” says Foster, who, like Albom, is a Detroit radio staple. “We always wondered how come we didn’t see that. How come we didn’t hear that? Mitch is a very talented writer. And sometimes he out-writes you. But sometimes he writes things that just seem too good to be true. My opinion? I think they’re going to find things they’ll question. My gut is that he will resign.”

Foster is one of several Detroit News writers who have been interviewed by the Free Press investigative team. The session lasted 90 minutes and, says Foster, “it was incredibly awkward.”

Free Press reporter David Zeman asked if Foster had ever witnessed any wrongdoings or fabrications by Albom, if he had ever been at an event that Albom wrote about but didn’t attend. “I felt uncomfortable doing it, because short-term, this is between the Free Press and Mitch,” Foster says. “But long-term, it’s about our business. This is something you have to do if you care about our profession.”

Others are simply flabbergasted by the episode.

“I’m baffled by the whole thing,” says Joe LaPointe, a sports columnist at the New York Times who left the Free Press in 1989. “When I worked with him, he was maybe the hardest-working sports columnist I ever saw. He was everywhere -- at Red Wings practice, at Tigers games. He really did work. But I just don’t get this. I understand the thing about the deadline problem, but it would have been so easy to write it a different way.”

*

Jekyll-Hyde personality

One of the most startling aspects of the discussion about Albom is how venomous it gets. While some of it is fueled by moral outrage, just as much seems to stem from resentment and flat-out jealousy.

For some, the anger is a holdover from the Free Press’ bitter 1995 strike. Albom crossed the picket line two months into the strike. Many reporters went back to work earlier, but Albom’s high profile made his return particularly infuriating to strikers. Typically, Albom remained busy while he was on strike, conducting the interviews that would eventually become “Tuesdays With Morrie.”

For others, especially those who know Albom personally, the animosity stems from what they feel is an enormous gap between the public and private man. Indeed, the stories about Albom’s bad behavior, particularly to underlings, are legion. For example, Lessenberry says one of his students quit an internship at WJR radio after Albom threw a computer keyboard at her.

Art Regner, co-host of a sports talk show on WXYT-AM, experienced Albom’s wrath firsthand.

“I remember one time when I was his producer, he was unhappy with the way something had gone,” Regner says. “Even if they were upset, most people would have a few words and that would be it. But Mitch -- Mitch screamed and screamed. It was a major tantrum.”

The flip side is that, in print and on the air, Albom connects with readers in a way that is uncommon in modern journalism. Critics say his writing is formulaic, but clearly it is a formula that touches readers deeply. Albom may be a millionaire megastar. But to readers, he’s one of their own, and they want to know what he has to say.

And, according to at least one former colleague, he feels that same sort of adoration for his readers.

Former Free Press sportswriter Bill Roose recalls a memorable trip home after a Detroit Lions game in Phoenix in December 2002.

“I asked him one question -- how do you do all of this? -- and he went into this unbelievable story that lasted for hours -- all the way home,” says Roose, who left to work for the Archdiocese of Detroit. “Sometimes Mitch wouldn’t give you the time of day. But this time, he talked of himself, asked questions about me, was supportive of me going back to school -- I was stunned.”

Roose was amazed by Albom’s work habits. “You’re at a game and it ends at 4. You go downstairs for interviews and come back up by 5:15 and Mitch is already wrapping up and going home. It always floored me. I knew I would be there writing until 7 p.m. And this wasn’t just once, this was every game.”

Roose also has a vivid memory of Albom getting emotional when he spoke of his love for newspapers, and in particular for the Free Press.

“He could have left the Free Press a dozen times,” Roose says. “But he has chosen to stay here in Detroit. He likes the other stuff he does too -- the books and movies -- but he said that if he had to pick just one, it would be newspapers. That’s what he was meant to do.”*

David Lyman, editor of the Chivas Life Guide, was a features writer and dance critic for the Detroit Free Press from 1995 to 2004.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.