Some Say, Hey, Mays of ‘90s Plays in Seattle

- Share via

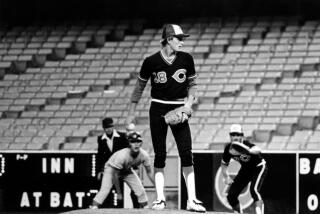

SEATTLE — How often do the realities exceed the myths, even for a legend in the making like Ken Griffey Jr.? With the Seattle Mariners’ prodigy of a center fielder -- known alternately as “The Kid,” “The Natural” or just “Junior,” depending upon whose turn it is to hand out the superlatives -- the actual surpasses the expected and the rumored regularly.

It’s just one of many traits possessed by baseball’s youngest and newest superstar that fall into the awe-inspiring, almost-frightening category. Griffey has become a conversation piece around the league, the player opponents gather around the batting cage to watch and about whom scouts and executives run up long-distance telephone bills, swapping tales of amazing exploits.

“I always have people around the league calling me for confirmation of something they heard Junior did,” Mariners batting coach Gene Clines said recently. “I’ll tell them it’s true, and then they’ll say something like: ‘No way. No one’s that good.’ And I’ll say: ‘This kid is.’ ... It’s nice to be around for the start of something big.”

Indeed, the making of a legend is something to behold. Griffey labors in relative obscurity here, though that will soon change if the Mariners sign his father as expected. But his exploits have demanded notice and have prompted comparisons to a young outfielder of four decades ago who also wore No. 24 -- Willie Mays. Mariners Manager Jim Lefebvre doesn’t particularly care for the parallel, but concedes he recognizes its validity.

“He’s a little of this, a little of that,” Lefebvre said. “I like to say there’s a lot of his dad in him. Junior and Ken Griffey Sr. really are quite a bit alike. But yeah, the Mays comparison probably has some merit, especially if you’re talking about defense.”

And Lefebvre does. He can reel off the memorable efforts of Griffey’s brief but glittering career: There was the nearly 400-foot throw to nab Robin Yount at third base as he tried to stretch a double into a triple, the lunging grab against the wall in Boston to rob Wade Boggs of extra bases and the back-to-the-plate snatch of a Rickey Henderson drive that conjured the clearest visions of Mays.

And, of course, there’s this season’s most celebrated defensive gem -- the breathtaking ascent over the Yankee Stadium fence to pull in a Jesse Barfield homer-to-be. That remarkable play left the New York outfielder with hands on hips and a disbelieving frown as he stood halfway between first and second while Griffey trotted past him to the Seattle dugout.

“That’s why I like to play defense,” Griffey said in his fidgety, apparently disinterested way. “It’s the only chance I get to make someone else mad.”

Plenty of American League pitchers would disagree. Griffey creates plenty of frustration with his bat -- a black Louisville Slugger that’s the same model his father uses, except that the younger Griffey has his weapons inscribed with “The Kid.”

Only a broken hand in July kept Griffey from being last year’s AL rookie of the year. When he broke in he was the youngest player in the majors at 19, and posted a .264, 16-home run, 61-RBI campaign that was less impressive statistically than it looked to first-hand observers. His grace afield and smooth left-handed stroke warned of the coming of an era of dominance.

A September skid that saw him hit .181 may have been his condensed searching-for-himself experience, for he has returned with a vengeance this season. Currently, Griffey is batting .306, in the league’s top 10. He has 17 homers and 60 RBI, and tops the AL with 151 hits. His 43 multiple-hit games also lead the league, and he is among the AL’s top 10 in runs, total bases and slugging percentage.

He led the league’s batting race for nearly a month before Henderson overtook him, and he became the second-youngest starter (to Al Kaline) in the history of the all-star game.

“The sky’s the limit for him,” said Griffey Sr., who recently agreed to go on the voluntarily retired list to help the Cincinnati Reds out of a roster problem but last week was waived instead. That should enable him to join the Mariners soon to finish out the season playing alongside his son. Last season, the two became the first father and son to play in the major leagues at the same time.

The elder Griffey makes certain to catch himself before the fatherly gushing goes too far. “Don’t tell him I said that,” he continued. “He’s hard enough for the Seattle coaches to deal with already.”

Therein lies the problem -- or perhaps a charming key to success -- with Griffey the younger. One of the most common words used to describe him is “difficult.” Those around him are quick to caution they don’t mean he’s a troublemaker or a malcontent; it’s simply that Griffey is only two years removed from high school and shows it.

“He’s not a bad kid,” his father said. “I’m certainly not trying to tell you that. It’s just that he’s not a student of the game. He listens to rap songs instead of studying pitchers. He operates on instincts and ability, and sometimes very little else. Once he matures a little bit -- and his mother isn’t sure that day ever will come -- he’ll be a very, very difficult opponent on a baseball field.”

These are the kinds of word-of-mouth stories that usually are found to be greatly exaggerated: A player doesn’t know who the pitchers are. He doesn’t know who the opposing batters are. He can’t distinguish good hitting mechanics from a weekend softballer’s stroke. Rarely are the tales borne out, at least not fully.

With Griffey, though, they’re almost all true -- or at least they were a few months ago. He admits he really didn’t know who Bert Blyleven was. He’s familiar with the repertoires and tendencies of only a few AL pitchers. He concedes he really didn’t know anything about any of the Baltimore Orioles except Cal Ripken Jr. When in doubt, he plays a straightaway center field and uses his extraordinary athleticism to compensate for any deficiencies in positioning.

“People try to make the game too complicated,” he said. “You hit the ball, you run, you go after it and catch it. You might not be able to figure out what pitch the guy’s going to throw you, but eventually he has to throw something across the plate that I can hit. It’s a simple game, really. I know what I can do.”

That casual approach has led him to make more than his share of head-scratching mistakes. During a recent series here against Baltimore, he swung at a borderline-low pitch from Pete Harnisch after Harnisch had begun the game by throwing 11 straight balls.

He gets picked off and throws to the wrong base occasionally. He possesses great speed, but has just 15 stolen bases in 25 attempts. He has drawn 55 walks -- a respectable total but not one that reflects the careful manner he is pitched to in virtually every at-bat.

He resisted when Lefebvre moved him from second to fifth in the batting order earlier this season, although he was immediately enamored with a later switch to third. When Lefebvre first asked him last year to show up for early batting practice -- a standard practice on his teams -- Griffey was alarmed.

An M.C. Hammer tape blasting through headphones is his preferred entertainment. He’s had a sports car since he got his driver’s license and an immense phone bill for as long as he can remember, courtesy of his father’s generosity and a family closeness that leads him to call home almost every night. His youthfulness is unabashedly intact.

Yet Lefebvre bristles at notions that Griffey is a wide-eyed kid acting on reckless instinct alone. He’s quick to remind that Griffey is learning the game, and learning it in the major leagues at an age when most players are doing the same in college or the minors.

The metamorphosis toward a veteran approach seems to be taking place already. Griffey says he has begun to note patterns in the ways he’s being pitched. He doesn’t live by those observations yet, but that might come. He recognizes more opponents, even if the purpose is a pre-game handshake rather than an intricate working knowledge of their playing styles.

Might he even have a handy notebook full of information on pitchers within a few years? “Nah, that would be taking it too far, I think,” he said. “I kind of like things the way they are.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.