FOUL PLAY

- Share via

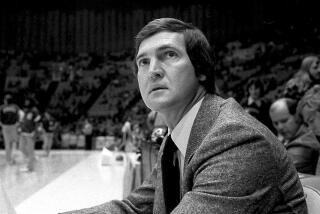

Part psychologist. Part drill sergeant. Part negotiator. Part motivator. And tactically, part Don Nelson disciple.

Mike Dunleavy encompasses all those qualities. Which can be a good and a bad thing.

More than a decade ago it made a Dunleavy believer of Jerry West, even before the Laker vice president had met the then-Milwaukee Buck assistant.

This season, it helped Dunleavy, as Portland Trail Blazer coach, juggle a team that even his second-year guard, Bonzi Wells, concedes has “10 to 12 great players with attitudes.”

“Attitudes” being the operative word.

But tonight, in Game 2 of the Western Conference finals, it has thrust Dunleavy into the highest profile of his NBA career after adopting the Hack-a-Shaq strategy that Nelson employed last November against Laker center Shaquille O’Neal. At the time the Dallas Mavericks first used the tactic, neither O’Neal nor Laker Coach Phil Jackson were impressed.

“Well, you can always count on Nellie to screw a game up, you know that,” Jackson said after the game against the Mavericks. “The guy’s on the [NBA] rules committee and he finds more ways to bend the rules than Richard Nixon did as president.”

But why is Dunleavy, whose team’s talent far surpasses Nelson’s Mavericks, resorting to Hack-a-Shaq now?

An argument can be made that when a star like O’Neal has made less than 50% of his free throws in the playoffs, logic dictates the strategy, which was employed even in Wilt Chamberlain’s day.

But no matter the reason, it seems clear Dunleavy is facing plenty of pressure to win this series, perhaps even more than Jackson, considering that time may be running out on the Trail Blazers.

Think about it.

If the Trail Blazers do not overtake the Lakers in the Western finals, they may be in trouble down the line.

Portland has promising young players such as Rasheed Wallace, Brian Grant, Damon Stoudamire and Wells. But the Trail Blazers also have Scottie Pippen, Arvydas Sabonis, Steve Smith, Detlef Schrempf and Greg Anthony--all veteran players who are closer to the end of their careers than the start.

With the league’s luxury tax right around the corner, and the Trail Blazers locked into contracts for the 2000-2001 season with 10 of the 12 players on their roster, owner Paul Allen, financially one of the world’s most influential men, could be looking at the strong possibility of paying large dollars with no championships in return.

Dunleavy says he does not worry about things like that. At this stage of his life, Dunleavy’s a coach. No more, no less.

“I came to Portland because I thought they had the best chance of winning,” said Dunleavy, who began his head coaching career with the Lakers in 1990 and led them to the NBA finals in his first season.

“It’s always better to have good players than not to have good players, let me tell you that. To work [good] players into a working combination or formula is the fun part of coaching. Players mostly want to win. If you put them in situations where they can win and keep it positive, things will happen for you.”

Rarely has it been more positive for Dunleavy than during his years with the Lakers in the early 1990s, but he nearly didn’t become a coach at all.

When he retired as an NBA player, he worked two years with a New York investment firm before he joined Del Harris’ coaching staff in Milwaukee as an assistant in 1986, thanks to the urging of Nelson.

In 1988, Dunleavy realized he was considered head coaching material after a conversation he had with West at a Los Angeles summer league game.

“He told me that, ‘As far as I’m concerned, in two, three years if I’m looking for a coach, you’re one of the first guys I’m going to talk to,’ ” said Dunleavy, who discovered then that West had his eye on him for years. “At which point, I said to him, ‘That’s great, I’m very flattered, but how can you say that? I don’t know you, we’ve never talked basketball, what do you base that on?’ ‘He said, ‘Does Nelly know you? Does Del know you? I’ve talked to them about you.’ ”

Two years later, West hired Dunleavy to replace Pat Riley.

In 1991, Dunleavy guided the Lakers to the NBA finals, with a Western Conference finals victory over Portland.

That earned him an opportunity that even West felt he couldn’t turn down.

“The opportunity he had at the time was so great,” West said. “He was to be the second- or third-highest paid coach in the league . . . it was an opportunity you couldn’t pass up for him and his family.” West was referring to Dunleavy’s eight-year contract to be the coach and vice president of basketball operations with the Bucks. What the Laker vice president didn’t know was Dunleavy left mainly because of his friendship with West.

“I know this sounds crazy, but I had this great relationship with Jerry West. We couldn’t have gotten along any better,” Dunleavy said. “I knew the deal would provide great security for my family and I would be moving to an area I was familiar with, but the key was I felt Jerry was a friend for life and that the only way I could ruin it would be to stay [in L.A.] and coach.

“I realized then that coaches are hired to be fired. This way Jerry and I would always be close. . . . My family and his are close and think it will always stay that way.”

West was touched by the sentiment.

“Obviously it is very nice to say something like that,” he said.

“Mike is one of the great guys in basketball. He did a great job for us under awkward circumstances.”

Dunleavy’s love affair with Milwaukee, however, was short-lived. In 1997, he resigned from Milwaukee to become the ninth coach in Trail Blazer history.

“Initially, the group of players we had were pretty emotional and pretty volatile,” Dunleavy said. “The first year we got knocked out of the playoffs by the Lakers in the first round.

“Our next goal was to try and be in position to gain home court in the playoffs and then to get past the first round. . . . We did that last year.

“It was a positive step for the franchise and the players. We gained experience and confidence.”

But that Trail Blazer team didn’t blend well in crunch time. The organization got rid of Isaiah Rider, Jim Jackson and Kelvin Cato, among others. Veterans Pippen, Smith and Schrempf were added.

“From the very beginning, my philosophy was that you win games with talent, but if you want to win championships, you need character and talent,” Dunleavy said. “Guys with good work ethic and are not going to fold when they hit adversity.”

Even now, his players know they are not an easy bunch to handle.

“It’s really tough coaching us,” said Wells, who spent almost all of last season on the bench. “If it wasn’t for our assistant coaches, I don’t know what Coach Dunleavy would do.

“We have so many guys he has to cater to. There are so many personalities. It’s kind of tough on Coach Dunleavy, but he does a great job juggling as much as he can. He can’t be the best all of the time. I kind of have to look at that. I now know he can’t make everybody happy every night.”

With his Hack-a-Shaq strategy Dunleavy is probably making few happy, although West remains a backer, even if he doesn’t agree with the tactics.

“The bottom line is Mike has done a terrific job [with Portland],” West said of the pressure Dunleavy faces with the Trail Blazers. “It is a situation where you hope for the best for people you like.”

But on Hack-a-Shaq?

“You hate to see it because I think it ruins the intent of basketball,” West said. “And, if you do it for a long amount of time, I think it hurts the team doing it because the focus is on fouling. Your team forgets to play the game. . . . I think Saturday’s game got out of hand.

“I don’t think anyone likes to see it and I’m sure Mike doesn’t either, but he knows it gives his team an option to win the game.”

That is one thing Dunleavy doesn’t intend to give up.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.