A Stroke of Inspiration for Women

- Share via

For moms and dads worried about how to pay for their daughters’ college educations, here’s a solution: Tell them to become rowers.

There are 80 universities competing in NCAA Division I-A women’s rowing. Each can offer a maximum of 20 scholarships, the most of any women’s sport.

The talent pool is thin because there aren’t many high school rowing programs this side of Seattle, Boston or the Bay Area.

It creates opportunities for girls to earn rowing scholarships to some of the most prestigious schools in America, from Notre Dame to Michigan, UCLA to Stanford, and USC to Duke.

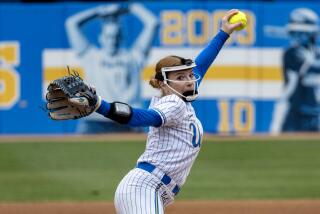

Unlike soccer, tennis, volleyball and softball, in which girls usually have to play for years in club programs just to develop the skills necessary to become a recruited athlete, rowing coaches have no problem identifying athletes as seniors in high school and turning them into rowers.

That’s what happened to Shannon Packer of Lake Forest El Toro High. She was a key member of El Toro’s tennis team, playing No. 1 doubles.

She heard about rowing competitions taking place at the Newport Aquatics Center, joined the junior crew and quit tennis this year. On Nov. 14, she signed a letter of intent with UCLA for a rowing scholarship.

“She’s probably the best on my team,” said Christy Shaver, coach of Newport Aquatics. “She has an ability to push it out every day. She gives everything. There’s no limitation to what she can do.”

Three other Newport Aquatics members also signed with UCLA, which will have rowers on scholarship for the first time next fall. They are Lauren May from Anaheim Canyon, a former volleyball player; Lindsey Hurban from Mission Viejo, a former soccer player, and Michelle Fickling from Mission Viejo Capistrano Valley, a former tennis player.

Let’s make something clear: Rowing is no easy sport.

“People generally either love it or hate it,” said UCLA Coach Amy Fuller, a three-time Olympian. “Anyone who thinks it’s a free ride into college is going to have a rude awakening.”

Calluses on your hands. A heartbeat of more than 160. Mental and physical exhaustion. Those are just a few of the obstacles to overcome.

“It’s 61/2 minutes of all-out rowing while using 80% of your body mass,” Fuller said. “It takes a real disciplined person to stick it out.”

Women’s rowing had its first NCAA championship in 1997 and continues to grow because it’s an effective way for schools to fulfill gender equity requirements.

“There is a huge opportunity for people who like to be on the water and work hard,” Fuller said.

Newport Aquatics has 110 athletes, ages 13 to 18, in its junior program, half of them girls. Some of the high school-age participants still try to compete in other sports but find it difficult.

“It’s nine months a year, five days a week, sometimes two times a day, plus races on weekends,” Shaver said.

Added Packer, “It’s one of the hardest sports I’ve ever done. There’s a lot of pain involved. Our hands get torn up.”

But rowers develop a special camaraderie to push past mental and physical barriers they once thought unbearable.

“There’s a special bond when you get in your boat and everyone is hurting for the same reason,” Packer said. “It’s the ultimate team sport.”

Fuller, who grew up in Westlake Village and didn’t start rowing until her sophomore year of college, has two scholarships to spread among her athletes next season. Each year, she’ll gain more money on the way to possibly 20 scholarships. But she plans to save some money for walk-ons.

Fuller believes she can improve her team by recruiting students at UCLA who have never tried rowing. There are numerous former high school athletes walking around campus. Each Pacific 10 rowing school has a novice team made up of first-year rowers.

“There are a lot of scholarships available and not a lot of high school rowers,” Fuller said.

OK, moms and dads, hide the tennis balls and softball bats and start showing your daughters how to row. It’s a quick way to improve the family finances.

*

Eric Sondheimer can be reached at eric.sondheimer@latimes.com

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.