Heated Debate About ‘Cool’ Cut

- Share via

In the musical “1776,” the song “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men” depicts Revolutionary War era conservatives as power-hungry wheedlers focused on maintaining wealth. So it’s not surprising that then-President Richard Nixon, who saw the show at a special White House performance in 1970, wasn’t a big fan of the number.

What is surprising is that according to Jack L. Warner, the film’s producer and a friend of the president, Nixon pressured him to cut the song from the 1972 film version of the show--which Warner did. Warner also wanted the original negative of the song shredded, but the film’s editor secretly kept it intact.

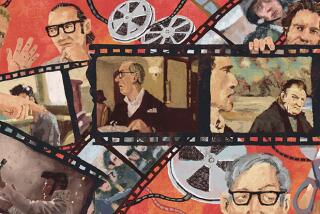

In the spring of next year, Sony Pictures--which owns the rights to the film--will release DVD and video versions of a new director’s cut of “1776,” restoring the original version of “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men,” prompting the director, writer and cast members to tell the strange tale of Nixon, Warner and the song.

Even in a politically charged era, “1776’s” dramatic portrayal of the struggle for integrity and personal honor in the second Continental Congress struck a chord with audiences from both sides of the political spectrum. “1776” was a hit, and by the time it beat out “Hair” for best musical at the 1969 Tony Awards, it was hardly a surprise that enthusiastic Nixon staffers would ring up to request a White House performance.

“They were so excited, they were going to have the Marine Band learn all the music,” says director Peter H. Hunt. The cast, however, had reservations about playing for Nixon. Actor Paul Hecht recalls a “very heavy discussion about whether we should even go.”

The politically active cast included Hecht, who played John Dickinson and went on to become the New York president of the Screen Actors Guild; SAG’s current president, William Daniels, who played John Adams; and Howard Da Silva, who played Ben Franklin. The last time Da Silva had received an invitation from Nixon, it was to testify before 1947’s House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), the anti-communist star chamber that Nixon helped to revivify during his time in Congress. Da Silva refused to talk and was subsequently blacklisted from Hollywood for many years.

The cast’s reservations turned out to be well-founded, Hunt says, when the White House called a second time. “All of a sudden they came back and asked if we would make some cuts in the show,” Hunt says. Hunt, librettist Peter Stone and the cast all felt it was no coincidence that the Nixon White House wanted to cut “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men,” a Broadway-style minuet sung by conservatives intent on steering the country, as Sherman Edwards’ lyric goes, “never to the left ... forever to the right.” Nixon staffers also requested excision of the song “Momma Look Sharp,” a dialogue between a dying soldier and his mother.

According to Daniels, the production stood its ground: “The producers told them no, absolutely not.” And Hunt adds, “We told them it was a kind of censorship.” Nixon’s staff dropped the request for cuts, and the cast decided that the show should play the White House.

Besides, for some of the more political cast members, this was as an opportunity. On the Sunday in early 1970 when President Nixon watched the unexpurgated “1776,” he got a little something extra during “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men.” As Hunt recalls: “Let’s just say the cast performed with additional verve. I was sitting right next to Nixon, and even I was getting nervous.”

Hecht, who led the number, reports that he delivered it “with a kind of Brechtian vigor, a vehemence--dare I say venom?” Hunt recalls that the end of the song left an icy moment of uncertainty in the air, which was broken by Nixon, who suddenly stood, shouting bravos.

“I think he had to do that, it was so tense,” Hunt says.

*

In 1971, when Hunt and Stone signed on as director and screenwriter, respectively, for the film version of their musical, they could not have known that they would once again hear “Considerate Men” and Richard Nixon’s name spoken in the same breath, this time by the film’s producer, Jack Warner.

Warner had been a big Nixon fan and campaign supporter, and the two had become friends over the years. (By this time in his career, Warner had retired as studio chief at Warner Bros. and had become an independent producer.) Also, when Warner was summoned before HUAC back in ‘47, he readily named a dozen screenwriters as Communists. (“Ideological termites,” he called them.) Finally, like the Nixon White House, Warner wanted cuts in “1776.”

Things went smoothly during filming, but it’s clear that Warner had problems with “Considerate Men” from the start. Hunt and Stone resisted the requests for cuts, and Warner initially backed down. Once the movie was finished shooting and was in post-production, director Hunt took his wife to Europe for a long-overdue honeymoon, confident that his film was safely on its way to the lab for printing; “1776” was Hunt’s first film, but it was Warner’s last, and he was about to give the novice helmer a doctoral degree in Hollywood politics.

According to Joe Caporiccio, producer of a 1990 laserdisc restoration of the film, editor Florence Williamson said that Warner told her he wanted “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men” cut out, claiming he had screened the film for the president, who asked that the number be excised.

When Hunt got back to the U.S. and found the number had been cut, he stormed into Warner’s office. “I asked him, ‘Jack, how could you do this?’ and he said, ‘With a pair of scissors.”’

Warner also told Hunt that he had ordered the negative of the cuts shredded, saying, “I don’t want history second-guessing me on this.” Meanwhile, editor Williamson showed less allegiance to Warner and more to film history by quietly putting all the negatives into storage, and there they remained until the Sony team working on the current restoration uncovered them.

Although Nixon’s diaries show that Warner had dinner with Nixon two months before the film “1776” opened, they do not show that a screening took place. What is almost certain though, according to those involved in the film, is that if Nixon did indeed ask that the number be removed, he was merely pulling the trigger on a target already well in Warner’s sights.

The film was a critical and box-office disappointment, but Sony Pictures is hoping that restoring the director’s original vision will give the film its structural teeth back and hopefully gain it a new audience. Commenting on the importance of “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men” within the story’s structure, Daniels said, “The number gives the play its balance.”

To the second Continental Congress, balance was an important--and eternally open--question. The Founding Fathers wanted to judge the quality of personal freedom by how safely it could be criticized, but did that also apply to artistic freedom? In Hollywood, at least, the question remains unanswered. “I felt somewhat raped [by Warner’s edits],” Stone says. “It was an invasion, but he had the power to do it, because he had the copyright. And the studio heads, they still have that power.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.