Whipple’s Disease: Rare but Treatable Systemic Infection

- Share via

Key Facts

- Whipple’s disease is caused by Tropheryma whipplei, a bacterium that can live harmlessly in healthy individuals.

- Joint pain can appear years before digestive symptoms like weight loss and diarrhea.

- The gold-standard diagnosis is a small intestine biopsy using PAS staining.

- Treatment involves long-term antibiotics, typically ceftriaxone followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

- Relapse, especially in the brain, can occur years after treatment, making follow-up essential.

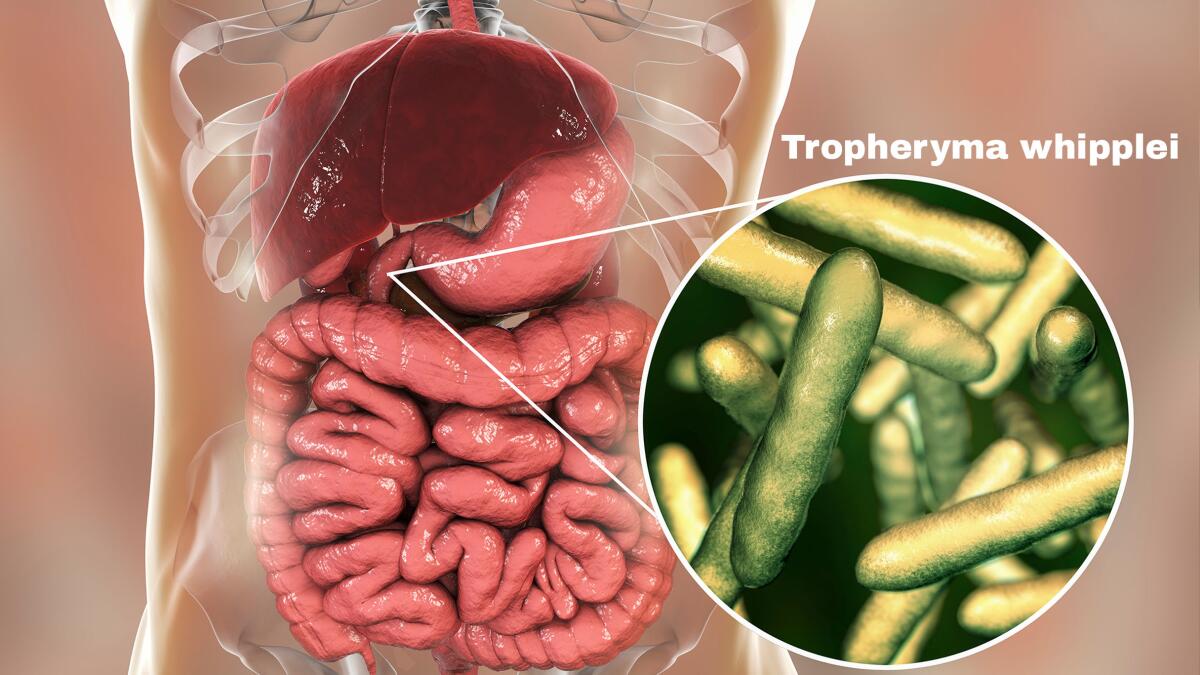

Whipple’s disease is a rare but serious systemic infection caused by the bacterium Tropheryma whipplei. It’s found in the environment and even in asymptomatic carriers but targets middle-aged white men and can affect multiple organ systems—especially the small intestine. Because its early symptoms mimic more common conditions, diagnosis often requires a combination of clinical suspicion and specific laboratory testing.

Table of Contents

- Etiology and Epidemiology of Whipple’s Disease

- Clinical Manifestations

- Pathophysiology of the Bile Duct

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Closing Thoughts

- References

Etiology and Epidemiology of Whipple’s Disease

Tropheryma whipplei is a gram-positive bacterium first identified in 1907 and later linked to a chronic, relapsing multisystem illness. It’s found in soil and sewage and can colonize healthy individuals without causing symptoms. But a small group—usually those with underlying immune system dysfunction—may develop full blown disease [1], [3].

Most patients with Whipple’s disease are middle-aged Caucasian men, so what about genetic susceptibility and hormonal influence [4], [11]? Although the bacteria can live harmlessly in some, defects in cellular immunity likely allow it to multiply unchecked and cause multisystemic illness [10].

Clinical Manifestations

Classical Form: Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

One of the weirdest things about Whipple’s disease is how slowly and subtly it can unfold. Many patients first present with joint pain or arthropathy which may appear years before gastrointestinal symptoms. Unlike inflammatory arthritis, this joint pain often has no redness or swelling so it’s hard to diagnose.

Once gastrointestinal symptoms start, they usually include chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain and significant weight loss—hallmarks of malabsorption due to damage to the gastrointestinal tract, especially the small intestine [2], [6], [8].

Other Forms

Whipple’s isn’t limited to the gut. The disease can take many forms depending on which organs are involved. Some patients have cardiac symptoms like endocarditis, while others may have neurological symptoms. Some have symptoms of which are neurological symptoms. Some have isolated CNS symptoms—known as isolated Whipple’s disease—without any gut symptoms at all. Children can also be affected, although this is less common. In pediatric cases, the disease often mimics acute infections with fever and lymphadenopathy [3].

Pathophysiology of the Bile Duct

Scientists are still figuring out how T. whipplei causes disease. What’s clear is that it hijacks the host’s immune system. The bacterium has been shown to replicate in host cells using interleukin 16 and induce cell death via apoptosis [3]. A subtle deficiency in the patient’s T-cell mediated immunity may be the reason why only some carriers develop disease [4], [2].

This impaired immunity prevents the body from clearing the bacterium properly, allowing it to invade the small intestine’s lining and spread through lymphatic and blood vessels to distant organs [9].

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Whipple’s disease can be tricky because of its many manifestations. The diagnostic gold standard is a small bowel biopsy—usually of the duodenum—with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining which highlights the characteristic foamy macrophages filled with T. whipplei [2], [6].

For confirmation, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing targeting the 16S ribosomal RNA gene of T. whipplei is widely used. Immunohistochemistry and DNA sequencing can provide additional molecular confirmation especially in cases without classic gastrointestinal symptoms [12].

Treatment

Whipple’s disease is one of the few systemic infections where antibiotic treatment can potentially cure the disease. But treatment must be prolonged and monitored closely because of the risk of relapse [5].

A common approach is to start with intravenous ceftriaxone for two weeks and then long term oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for at least one year [7]. For patients who cannot tolerate this regimen, a combination of hydroxychloroquine and doxycycline has been used successfully [7].

Since the disease can affect the CNS, some experts recommend regimens that can cross the blood brain barrier. Relapses, especially of the brain, can occur years later so long term follow up is essential.

Closing Thoughts

Whipple’s disease is a rare and fascinating illness that challenges clinicians with its many manifestations and slow progression. It often starts with vague joint pain or chronic digestive issues and can eventually affect almost every organ system—including the heart and brain. But with the right diagnostic tools and long term antibiotic treatment many patients can recover significantly.

Research into the immunological mechanisms of susceptibility may one day lead to more targeted treatments or even prevention. For now awareness and early recognition are the best tools to fight this elusive disease.

References

[1] Marth T. (2016). Whipple’s disease. Acta clinica Belgica, 71(6), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2016.1256586

[2] El-Abassi, R., Soliman, M. Y., Williams, F., & England, J. D. (2017). Whipple’s disease. Journal of the neurological sciences, 377, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2017.01.048

[3] Puéchal X. (2013). Whipple’s disease. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 72(6), 797–803. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202684

[4] Marth, T., & Raoult, D. (2003). Whipple’s disease. Lancet (London, England), 361(9353), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12274-X

[5] Schwartzman, S., & Schwartzman, M. (2013). Whipple’s disease. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America, 39(2), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2013.03.005

[6] Ratnaike R. N. (2000). Whipple’s disease. Postgraduate medical journal, 76(902), 760–766. https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.76.902.760

[7] Biagi, F., Biagi, G. L., & Corazza, G. R. (2017). What is the best therapy for Whipple’s disease? Our point of view. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 52(4), 465–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2016.1264009

[8] Mönkemüller, K., Fry, L. C., Rickes, S., & Malfertheiner, P. (2006). Whipple’s Disease. Current infectious disease reports, 8(2), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-006-0004-x

[9] Ramaiah, C., & Boynton, R. F. (1998). Whipple’s disease. Gastroenterology clinics of North America, 27(3), 683–vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70026-1

[10] Marth, T., & Strober, W. (1996). Whipple’s disease. Seminars in gastrointestinal disease, 7(1), 41–48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8903578/

[11] Bai, J. C., Mazure, R. M., Vazquez, H., Niveloni, S. I., Smecuol, E., Pedreira, S., & Mauriño, E. (2004). Whipple’s disease. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association, 2(10), 849–860. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00387-8

[12] Fantry, G. T., & James, S. P. (1995). Whipple’s disease. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland), 13(2), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1159/000171492