Coronavirus keeps TV news anchors at home but not off the air

- Share via

NEW YORK — Every weekday morning since March 25, Boston University sophomore Nick Mason, gets up at 5:45 a.m. to frame a TV camera shot in the dining room of his family’s apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

By 7 a.m., his father, “CBS This Morning” co-host Anthony Mason, will be connected on-screen with his colleagues Gayle King and Tony Dokoupil — also broadcasting from their New York area homes — a new ritual for network news under the shelter-at-home orders aimed at containing the coronavirus pandemic.

“There is just the two of us,” said Mason. “So when something goes wrong, especially when you’re on the air, it’s a little scary, but that’s what life is like right now.”

Maintaining the flow of information about the crisis is a critical task for network and cable news, which have seen their audience levels surge. But it has also forced journalists to confront the danger posed by the outbreak of the highly contagious virus, especially in New York, which has become the epicenter of the crisis (the number of coronavirus cases in New York state hit 130,689 on Monday). Two people in the network TV news ranks have died after contracting the virus, while a growing number of personnel including CNN anchors Chris Cuomo and Brooke Baldwin have tested positive.

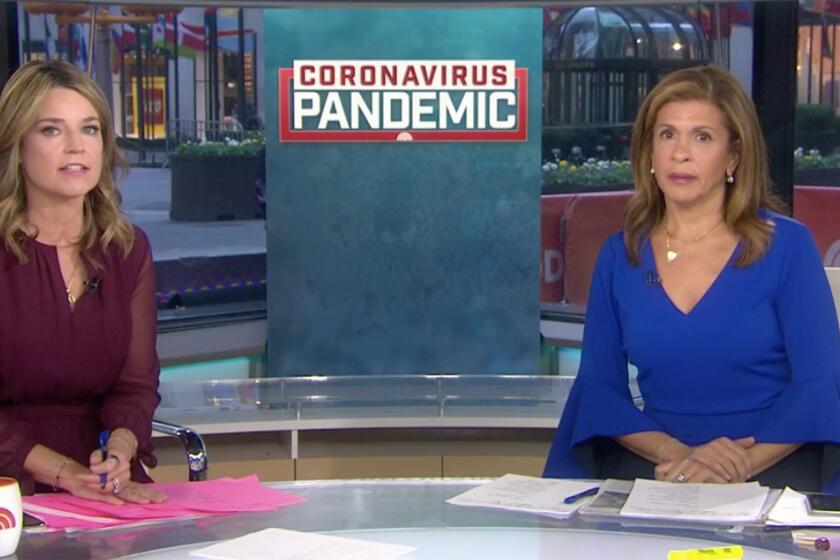

Guests and anchors practice social distancing as more staffers test positive.

The response has been to have anchors broadcast remotely, which is testing the technological adaptability of network, cable and local outlets.

Cuomo has continued to do his nightly CNN program from the basement of his Long Island, N.Y., home while suffering from symptoms of the virus. Fox News has a total of 42 home setups for its on-air talent.

On-air talent is used to being surrounded by a major support system that includes teams of people — technicians, producers, make-up artists and hairdressers. Even Mason only has the help of his son until 9 a.m., when Nick heads to his bedroom to take his college classes online.

It doesn’t always go smoothly. Last week, Mason read the scripted portions of the program off his laptop computer as the prompter he had set up at his home had failed.

“I always had appreciation for the crew that puts on the show,” Mason said. “I have five times more appreciation now.”

Like many of his peers, Mason has been forced to improvise without a playbook.

His apartment is the third outside location where he has done “CBS This Morning” in the last two weeks. He and his co-hosts moved out of the network’s broadcast center on West 57th Street to its Washington, D.C., studios after it was first learned that employees tested positive for the virus.

The program later moved to the Ed Sullivan Theater, the home of “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert,” before all three hosts were instructed to work from their homes in order to comply with stay-at-home orders.

Broadcasting remotely became an early option for NBC News, even though it was not in the network’s disaster recovery plan.

The network was among the first to keep members of its on-air talent roster at home after a staff member on “Today” tested positive for the virus on March 16. Three days later, Larry Edgeworth, a longtime NBC News audio technician with existing health issues, died after testing positive for the coronavirus.

Stacy Brady, executive vice president and general manager of news field and production for NBC News, said when the division’s executives first sat down around March 16 to come up with a long-range coronavirus strategy, she saw how the network already had in-home setups for several of its regular on-air contributors who regularly appear on cable news channel MSNBC.

“We move them from home to home depending on the contributor,” Brady said. “In my brain I said ‘that’s what we thought we should be doing,’ and I actually thought I’d order some equipment at that time. I wanted to be prepared for it.”

To broadcast from home, an anchor needs a prompter for the script copy they read, a TV monitor in order to watch what is going out on the air, and often a large screen where a background can be shown behind them. Some are also equipped with a LiveU, a portable cellular device about the size of a small laptop that transmits video over the internet and mobile networks back to the master control, where the broadcast signal is sent out.

Anchors have used social media to give viewers a sense of their new reality. NBC News veteran Andrea Mitchell’s Twitter account showed husband and former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan watching her in action from their Washington, D.C., home.

Guests and contributors who are not carrying an entire program themselves can get by using Skype of FaceTime, but even they need some help.

“We’ve sent them a style guide with tips and tricks of what’s the best way to make your Skype look as good as you can,” said Marc Greenstein, vice president, creative production design for MSNBC. “We’ve also sent out consumer grade mics and lighting kits which is something you get at Best Buy, just to up their game. We’ve sent them signs and props for book shelves just to get branding in.”

For Brady, the biggest obstacle has been navigating the varying internet speeds and reliability in different households.

“We are trying to run all of this broadcast on their internet while their whole families also are trying to work from home,” she said.

Precautions are taken with the installation of equipment amid the stay-at-home orders. Mason and his son assembled the studio themselves as they had been exposed to a family member who had coronavirus symptoms.

Mason’s “CBS This Morning” co-host Dokoupil has two broadcast setups in his home as his wife, Katy Tur, is a daytime anchor for MSNBC. Brady said having the couple use the same equipment would have increased the risk of requiring a technician to enter their home to make adjustments.

“The minute you start playing around with the lights or start messing around with the mixer or whatever you’re doing, we have to go back to the house,” Brady said. “For their safety and health and for our safety, we’re trying to make one trip and just kind of leave it.”

Dokoupil had CBS install a 60-inch monitor to cover a cracked wall in the basement of his New York City townhouse where his studio is set up. The parents of an infant son, Dokoupil and Tur have made other adjustments as well.

“We let the baby’s bedtime slide a little, hoping he’ll sleep a little later into the morning show,” he said. “That helps.”

Mason is content to let viewers get an intimate glimpse of his domicile. A painting of Piazza San Marco in Venice that he bought at an auction in the old Soviet Union in the early 1990s is often seen over his shoulder. It has gotten attention from fans on social media.

“I didn’t want to turn my home into a slick-looking TV studio — it’s a New York apartment,” Mason said.

Mason has gotten used to the new routine, but there are other obstacles ahead as the crisis is likely to go on for weeks if not months.

“My hair is getting really long and I’m going to be doing the show with a ponytail if this goes on another month,” Mason said. “I don’t think CBS News President Susan Zirinsky would appreciate it. The last time I gave myself a haircut I was five years old and it did not go well.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.