Aviation hero Bob Hoover, the last of a daredevil era, helped launch the jet age

- Share via

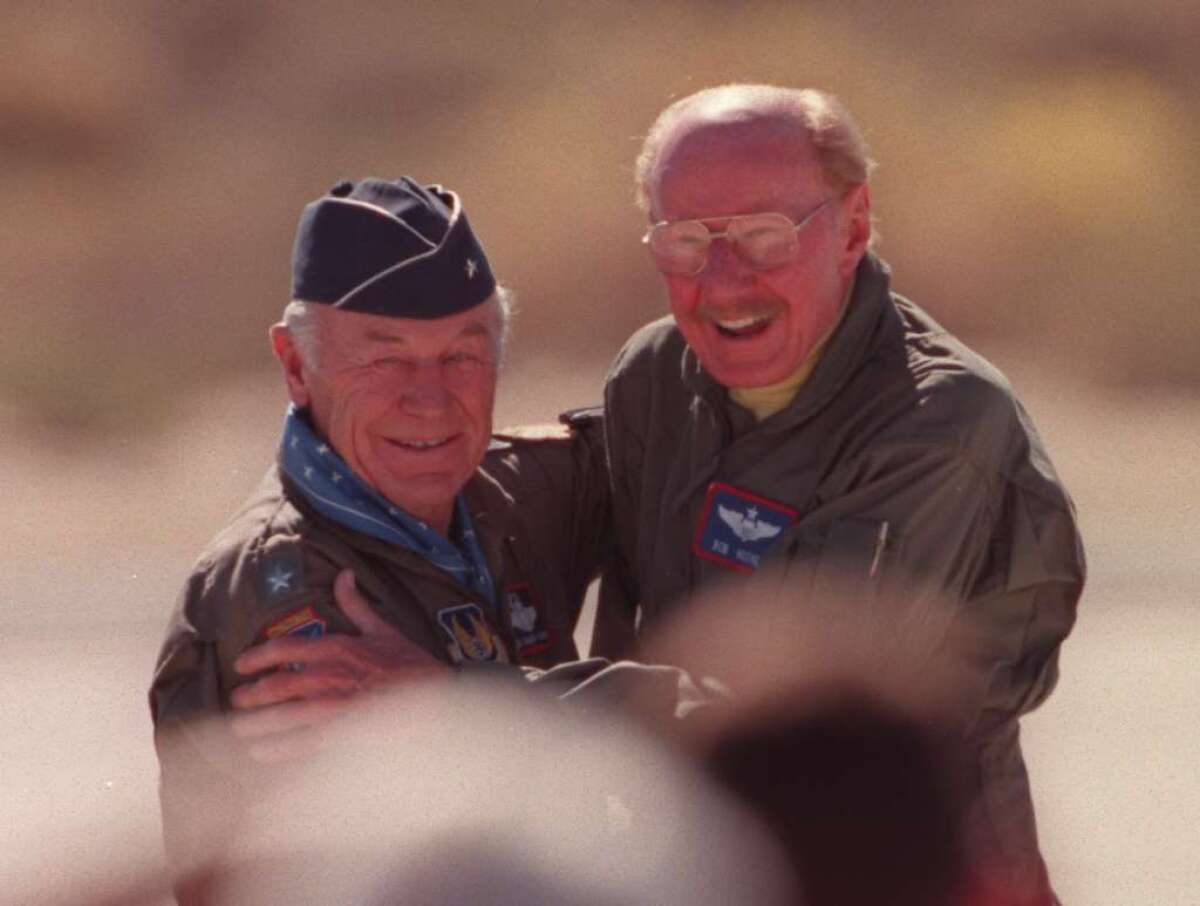

Few among Southern California’s early aerospace icons occupied a position as rarefied as Bob Hoover.

The legendary flier — who fought in World War II, helped launch the jet age as a military test pilot and later became a top air racer — was considered one of the best “stick and rudder” men in the world. According to those who knew and flew with him, Hoover possessed a combination of technical knowledge and athletic instincts that allowed him to perform when others could not.

The Palos Verdes Estates resident, considered the last of an era of aerial daredevils, died Tuesday, according to a family friend. He was 94.

Achievements that would have been the crown jewels atop any other airman’s resume seemed to come regularly to him: For instance, Hoover escaped from a Nazi prison camp, fleeing the country in a stolen German plane.

And while his career was marked by accomplishments, the veteran pilot also survived five separate crashes, giving him a unique perspective on his craft.

“I have been broken up from head to toe,” Hoover said in a 2014 interview.

He would take an airplane off the line ... and do all the things that the Air Force, during training, were convinced would kill you.

— Paul Tackabury, retired Air Force pilot

He ejected out of one of the first combat jets, the Republic F-84, in 1947 and hit the tail at 500 mph — breaking both legs and injuring his face. Several years later, he was trapped in a disabled F-100 Super Sabre that slammed into the desert, bounced 200 feet back into the air and then slammed down again. That accident broke his back, and rescue crews had to cut Hoover free from the wreckage.

He flew nearly 300 types of aircraft during a career as one of the country’s premier test pilots, rocketing across the Mojave Desert at a time when Southern California was the epicenter of aviation advancement.

Hoover brushed elbows with the likes of Charles Lindbergh, Jimmy Doolittle and Paul Tibbets Jr., pilot of the Enola Gay bomber that dropped the first atomic bomb. His own name was etched alongside those legends early in his career, when he served as the backup pilot in the Bell X-1 program, flying the chase plane when Chuck Yeager first broke the sound barrier in 1947.

Paul Tackabury, a retired Air Force pilot who ran the testing program at Northup Grumman Aerospace Systems, said it was Hoover’s ability to carefully test the limits of any aircraft’s maneuverability that turned him into an aerial wizard. Shortly after he graduated test pilot school in the 1960s, Tackabury said, he was on an Air Force base in London when he first saw Hoover take flight. Back then, he said, the Air Force pushed caution.

“The Air Force’s approach was to scare the crap out of the new trainees,” he said. “They’d show you all the crashes that happened and say: ‘See, you better pay attention.’”

Enter Hoover, who took to the skies to the delight of the pilots and the horror of the command staff.

“He would take an airplane off the line, same ones we were flying, and he would take it up and demonstrate it and do all the things that the Air Force, during training, were convinced would kill you,” Tackabury said.

But it was Hoover’s affable nature and refusal to get drunk on his own hype, friends said, that they will remember most.

John Tallichet — owner of the Proud Bird restaurant near Los Angeles International Airport, which serves as a hub for those in the aviation industry — said Hoover acted like any other customer, even though the building housed an area dedicated to the legendary airman.

“It was kind of the living legend that still you could interact with and he would be very talkative … I think a lot of these guys, either their health was frail or they … weren’t approachable,” Tallichet said. “I think he’s a connection to an era, ‘The Right Stuff,’ that I think was very powerful to my generation.”

Even if Hoover wasn’t quick to embrace his status, others had no hesitance in reminding him.

During the Living Legends of Aviation Awards dinner earlier this year, actor Harrison Ford recalled a 2015 incident where his vintage plane lost power over Santa Monica, causing an emergency crash landing on a golf course.

Ford said there was only one man’s advice that helped him survive the ordeal.

“You were there in my head, and in my heart,” Ford said, sitting beside Hoover. “Telling me the right thing to do, as you have for many other aviators throughout your long career.”

Follow @RVartabedian for aviation news and @JamesQueallyLAT for crime and police news in California.

ALSO

Barry Socher, composer and longtime L.A. Philharmonic violinist, dies at 68

‘The radical inside the system’: Tom Hayden, protester-turned-politician, dies at 76

Herschel Elkins, California attorney who helped write Lemon Law, dies at 87

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.