A California way to help the unemployed even if Washington won’t

- Share via

State Rep. Phil Ting (D-San Francisco) floated an idea last week: If Washington doesn’t re-up its $600 weekly unemployment boost, California should open a loophole that would allow Sacramento to borrow from the feds and continue the payments regardless.

It’s a fitting proposition for a state where belief in government proactively working for the public good has often led to experimentation, rather than mere talk. (See Stockton’s first-in-the-nation universal basic income pilot program — $500 a month paid to 125 people resulting in “really rational” purchases, according to one investigator tracking the project.) Ting’s proposal deserves a go-ahead if Washington doesn’t act.

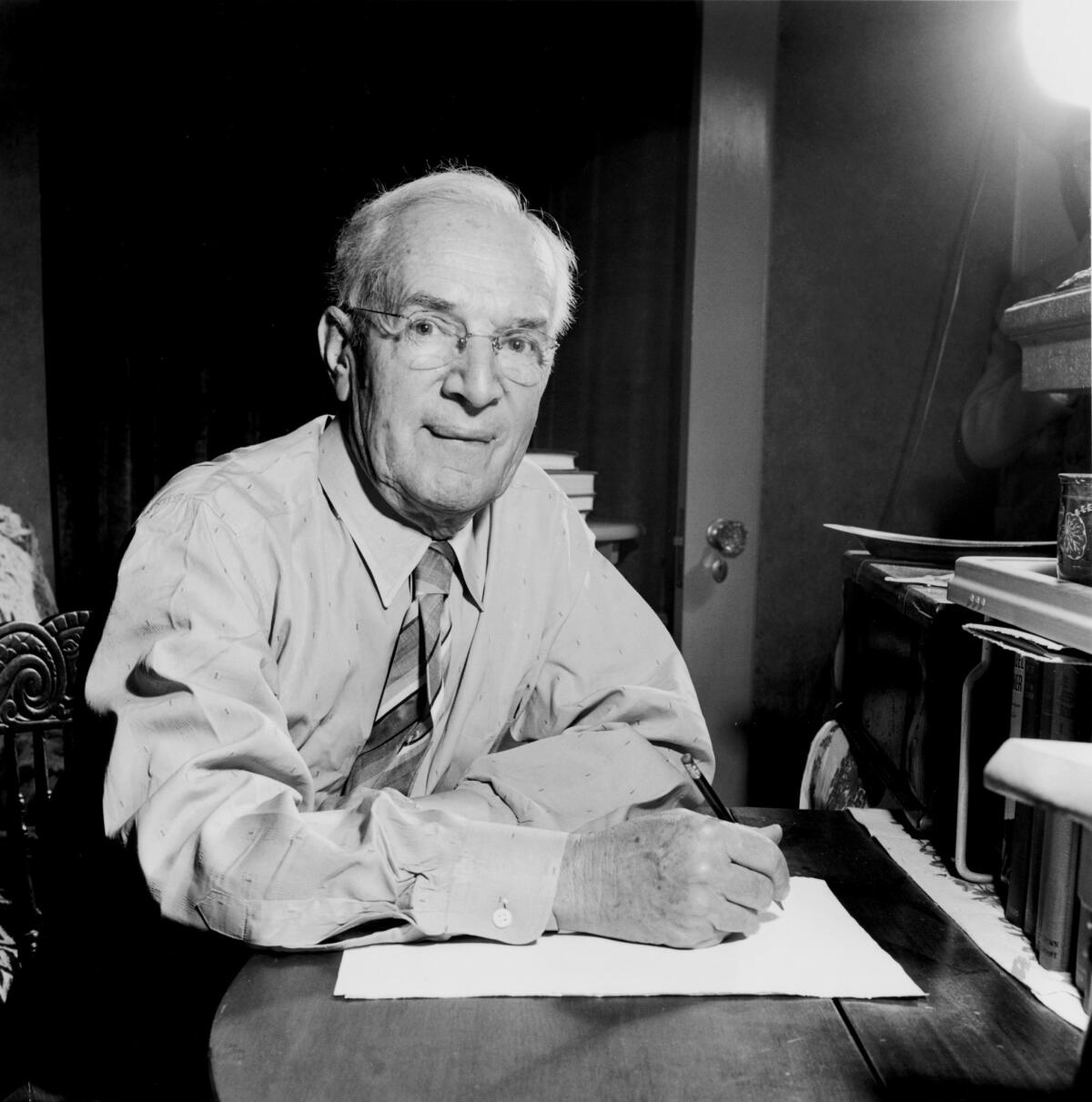

This kind of DIY progressivism has been a factor in California politics for better than a century. Its markers include the initiative and proposition system championed in 1911 by Republican reform Gov. Hiram Johnson, and — more to the point — the End Poverty in California gubernatorial campaign staged in 1934 by Upton Sinclair, the muckraking author of “The Jungle,” “Oil!” and more than 100 other works.

Workers crammed virtually shoulder-to-shoulder to tend production lines moving at inexorable speeds, high rates of disease and injury, low pay and unforgiving rules on time off or meal and bathroom breaks. Descriptions of today’s meatpacking industry sound lifted from Upton Sinclair.

Sinclair ran for governor, and lost big, as a Socialist in 1926 and 1930. In 1933, he re-registered as a Democrat and released his EPIC platform in a pamphlet called “I Governor, and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future.”

In the heat of the Depression, Sinclair wanted the state to take control of shuttered businesses and farms and turn them into cooperative work camps to put the unemployed legions back to work. Another “plank,” the one reminiscent of Ting’s proposal, promised $50 a month to those who couldn’t work — the disabled and the elderly — an amount equivalent to nearly $1,000 today.

Sinclair won the Democratic primary in a landslide, but he also provoked establishment enemies and a disinformation campaign. Spearheaded by MGM chief Louis B. Mayer, the attacks played out in newspapers and newsreels. In one particularly egregious instance, the Los Angeles Times published a front-page photo of disheveled men descending from a box car, purportedly drawn west by the promise of that 50 bucks. The image, it turned out, was a still from the 1933 Warner Bros. film “The Wild Boys of the Road.”

Sinclair lost the general election by 11 percentage points to Republican, and avowed anti-socialist, Frank Merriam, with the Democrat’s vote also affected by a third-party candidate. Sinclair’s fate reminds us that fake news is hardly an invention of the 21st century and that, along with its liberal leanings, California has always also had a strong strain of reactionary nativism. Just two years after the election, in 1936, the Los Angeles Police Department would deploy more than 100 officers — the “bum brigade” — to keep Dust Bowl migrants on the other side of the state line.

Sinclair’s losing candidacy was nonetheless influential in New Deal policies and it helped rejuvenate the Democratic Party in a state where “as late as 1931,” historian James Gregory has written, “not a single Democrat held statewide office.”

In 1938, Culbert Olson — elected to the state senate as an EPIC candidate — defeated Merriam to become the state’s first Democratic governor since 1894. EPIC didn’t usher in a progressive groundswell, but it did help set in motion the push and pull between left and right that gives even centrist politics in California today a progressive bent.

It’s not a stretch to argue that Sinclair’s campaign, and perhaps especially the promise of full employment or $50 a month, helped bring to the mainstream what would later emerge as the state’s encompassing (if still to be perfected) social safety net — affordable quality higher education, equal opportunity legislation and a version of collective healthcare.

Ting’s plan echoes Sinclair’s ideals and EPIC’s brash call for active governing. Since Congress passed its first coronavirus stimulus in March, states have already been borrowing from the feds to cover the $600 unemployment increase. Ting’s innovation merely extends that, with no need of Congress’s specific cooperation. Sinclair would admire the moxie.

In 1933, with state unemployment at 28%, the commandeering of fallow farms and shuttered factories seemed, for nearly 40% of California voters, a reasonable risk. With Congress stalemated and unemployment now at 14.9%, it’s entirely in character for us to try again to write the future on our own terms.

If government has any use, it is to help people in a time of crisis. That’s the essence of the Ting proposal, as well as EPIC’s enduring legacy.

David L. Ulin is a contrbuting writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.