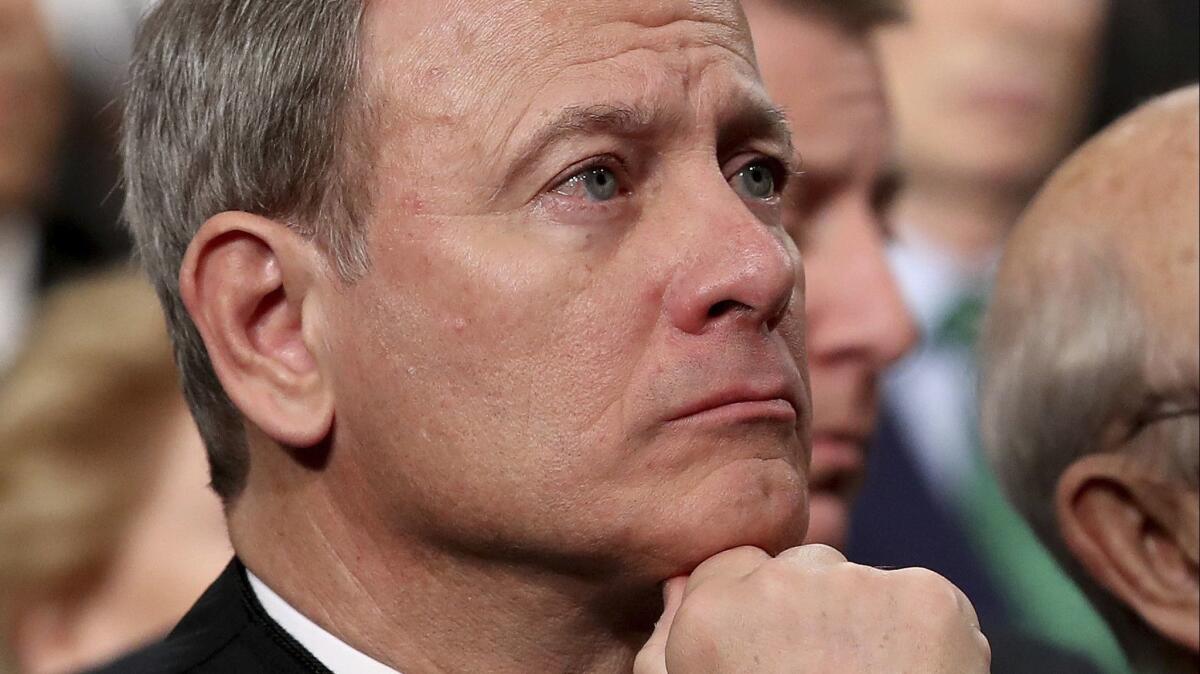

Supreme Court with Roberts in charge: Conservative, but not always predictable

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — The Supreme Court, despite the emergence of a new conservative majority, ended its annual term last week signaling an inclination to go slow, but spring a few surprises.

The court did not move aggressively to the right, as many Democrats and liberal activists feared and many abortion foes had fervently hoped.

Instead, with Chief Justice John G. Roberts firmly holding the ideological center — a position once held by retired Justice Anthony Kennedy — the court took a cautious path, reflecting Roberts’ determination to avoid the appearance of a court that is predictably conservative.

Even President Trump’s two appointees — Justices Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh — did not march in lockstep to advance the conservative legal agenda, taking different paths in several important cases.

“For the last dozen years, this was the Roberts Court in name only, and the Kennedy Court in reality. Now, it’s really John Roberts’ Court,” said University of Chicago law professor Daniel Hemel, a former court clerk.

Roberts knows the court “risks being seen as an entirely partisan institution if every ideologically divisive case breaks 5-to-4 conservative-to-liberal. So I think we can expect to see him voting against ideological type — at least occasionally,” Hemel continued. “There will still be lots of 5-to-4 conservative-to-liberal decisions, but I think Roberts understands the damage to the institution if every high-profile case breaks that way.”

For much of this term, the chief justice acted to put off major decisions on abortion, gun rights, transgender troops in the military, as well as an explosive clash over the rights of Christian bakery owners to refuse to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple.

Roberts’ dominant role was on full display on the final day in two major cases on political power, both effectively decided by the chief justice.

First, Roberts dashed the hopes of liberal reformers with a 5-4 ruling that closed the federal courts to claims of partisan gerrymandering.

In the opinion, joined by the four other conservative justices, Roberts said there was no legal formula or mathematical rule for a judge to decide when an election map drawn by state legislators crosses a line to become unconstitutionally partisan. Therefore, judges should stay out of this business, Roberts said in the North Carolina case called Rucho vs. Common Cause.

This was not a new idea for the chief justice, but with Kavanaugh having replaced the wavering Kennedy, who remained open to deciding gerrymandering cases, Roberts had the five votes he needed.

Immediately after announcing that conservative victory, Roberts began to slowly read his opinion in the term’s final case: a challenge to the Trump administration’s effort to put a citizenship question on the 2020 census for the first time since 1950.

States dominated by Democrats — led by California and New York — had sued over the move, and census experts predicted millions of immigrant families would refuse to answer, thereby knocking down the population counts in areas most likely to vote for Democrats.

Roberts explained the court was deciding only a “narrow” matter under the Administrative Procedure Act, not a grand constitutional issue.

But the chief justice noted that Trump’s commerce secretary, Wilbur Ross, had supplied only “contrived reasons” for adding the question.

No one believed a block-by-block count of citizens was needed to enforce the Voting Rights Act, as Ross had testified, Roberts concluded. “In these unusual circumstances, the district court (in New York) was warranted” in its decision to block the question, “and we affirm that disposition.”

The “we” in that one paragraph included only the four liberal justices who joined Roberts. They had dissented on much of the rest in Dept. of Commerce vs. New York, while the four conservatives dissented from the crucial Part V of the chief justice’s five-part opinion.

The surprising result angered the four other justices on the right. All year, they were frustrated with the chief justice’s cautious approach.

“A politically fraught issue does not justify abdicating our judicial duty,” Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Gorsuch wrote in December after the court in Box vs. Planned Parenthood refused to hear Indiana’s bid to deny Medicaid funds to Planned Parenthood clinics.

In May, the court refused to hear Indiana’s appeal of another law that would have prohibited abortions when a fetus was diagnosed with Down syndrome or any other disability.

And on Friday, the court refused to hear Alabama’s appeal of a law that would have ended nearly all second-trimester abortions. It takes only four votes to grant review of a case, indicating that Kavanaugh, like Roberts, is not ready to rule soon on abortion.

“The most controversial cases taken this term were ones where the court had no choice,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law. The court was obliged to rule on the partisan gerrymandering issue because federal courts in North Carolina and Maryland struck their election maps, and the state had a right to appeal. And in the census case, Trump’s lawyers said the government needed a ruling by July.

“I think after the Kavanaugh hearings, the justices wanted a lower profile term — and, overall, they succeeded,” Cherminsky said, recalling Kavanaugh’s bruising confirmation.

The conservative justices were not themselves always united, however.

Gorsuch, for example, is a strict libertarian who is skeptical of government power, whether in hands of federal regulators or police and prosecutors. This unusual combination aligns him with the conservatives on many cases but with the liberals on some.

Last week, he spoke for a 5-4 liberal majority that overturned part of a vaguely worded 1980s crime law that tacked on as many as 25 extra years in federal prison for thousands of convicts already serving time for crimes such as robbery. “Vague statutes threaten to hand responsibility for defining crimes to relatively unaccountable police, prosecutors and judges,” Gorsuch said in United States vs. Davis. In dissent, Kavanaugh called the decision “a serious mistake.”

For his part, Kavanaugh is a more traditional conservative, but he spoke for a 5-4 liberal majority in a case that clears the way for Apple to be sued in an antitrust suit, alleging it wields monopoly power over apps on the iPhone.

Kavanaugh also wrote this year’s most important opinion on racial bias, overturning the murder conviction of a Mississippi man who was tried six times by nearly all white juries.

“Equal justice under law requires a criminal trial free of racial discrimination in the jury selection process,” Kavanaugh said in Flowers vs. Mississippi. The white prosecutor had repeatedly sought to exclude African Americans, he said, and “we cannot ignore that history.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.