Rick Obrand is part collector, part historian and fully a fan of City Section sports

- Share via

With the grandeur of professional sports in Los Angeles casting a long shadow, the memories of many high school sports career can fade into darkness.

But in a room at the end of the hall in Rick Obrand’s quaint Harbor City condo — a small corner office that used to be a bedroom for his sons — those memories remain very much alive.

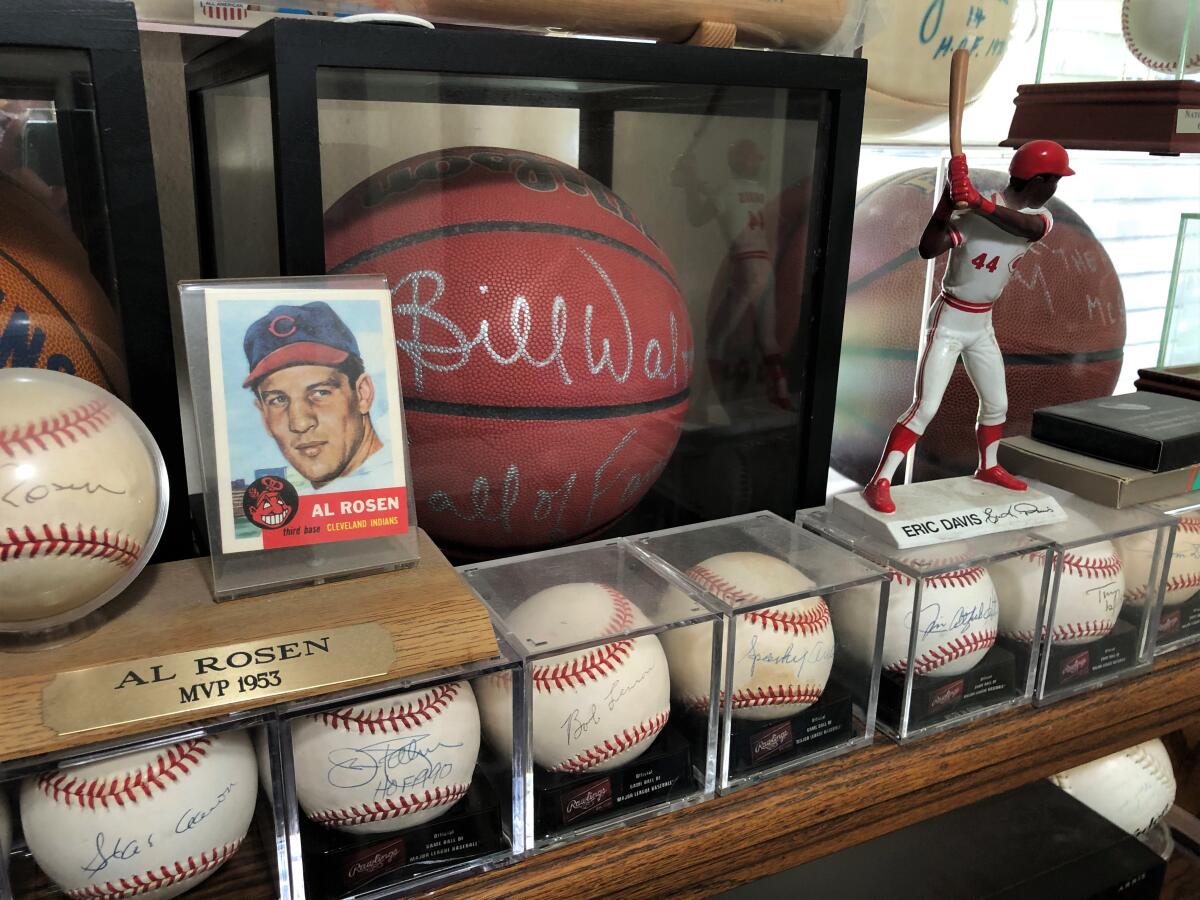

It’s the 74-year-old Obrand’s life’s work, a museum of treasures. Folders of detailed reports on alumni from every school — across the United States and beyond — stacked a bookcase high. Thousands of never-before-seen letters, addressed to Obrand, from professional athletes writing about their high school days.

He’d never sell any of it. The papers, the binders, the photographs — they all keep alive the memory of the athletes who through the decades would trot out on their local field to support their community.

“I’d like to really press both the district and the state legislators around how important prep sports are in our cities, in our communities, in our barbershops, all that kind of stuff,” says Bob Collins, the Los Angeles Unified School District’s former chief instructional officer. “I think that’s the legacy of Rick.”

About 15 years ago, Collins became interested in tracing the history of prominent graduates from Los Angeles schools. Working with an alumni committee, he was referred time and again to Obrand, whom they described as a human encyclopedia.

When Collins began to speak with Obrand, he was amazed. There was no name the man couldn’t trace back to some high school, with a list of their accomplishments there.

Years later, he’s still astounded. Collins talked to Obrand recently, giving him a name he was sure Obrand wouldn’t know — Roger Wagner, a former choral musician. Obrand responded that Wagner was a decathlete in the 1919 Olympics who ran for France.

“I said, ‘What? How can you possibly know that?’” Collins said. “He’s just a remarkable human being.”

The archives in the office don’t receive many visitors, though. Obrand hardly ventures into the room’s tight corners anymore, bedridden for the last two months because of sepsis. Moving from his at-home hospital bed to his wheelchair is a difficult task.

Doctors discovered a tumor the “size of a golf ball” on his kidney in March 2013. After the cancer diagnosis, they told Obrand he had six months to live. Eight years later, he’s still here, and he never stopped his research.

“I’m kind of a fighter,” Obrand said. “I’m a quiet guy, but I’m a fighter.”

Even confined to his bed, he’ll rattle off facts, his encyclopedic brain still churning. What do actor Robert Redford, actress Natalie Wood and former Dodgers star pitcher Don Drysdale have in common? They all went to the same high school, Van Nuys, Obrand will tell you.

“I know he’s very, very ill,” Collins said, “but his mind is still, phew! I’ll tell you.”

When Obrand was 9 years old, his father would drop him off at the Helms Athletic Foundation in Los Angeles so he could copy down their wealth of high school athletics records. Founder Bill Schroeder, who became a second father to Obrand, taught him how to disable the alarm system so he could burn midnight oil, scribbling down information on pieces of paper in a folder he’d brought from home.

Obrand played basketball at Washington High. At halftime during his away games, he said, his coach would let him sneak into the trophy rooms so he could copy down the information.

“I loved sports from the time I was a little kid,” Obrand said. “And I always thought, ‘This is going to be interesting, who went to what high school.’”

Obrand began teaching sixth grade at Carson Street Elementary School in his early 20s, a job he held for 40 years that yielded a dozen teacher-of-the-year awards. Around the same time, he began a practice of writing to athletes he’d research, asking them about their mentors and sources of inspiration in their youth.

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

One of his favorites out of the thousands of responses is from the late John Arnett. The former All-Pro running back for the Rams wrote of a fifth-grade teacher, Janice McKeever, who told him he could climb as high as he wanted as long as he worked hard enough.

“My second-grade teacher was also Janice McKeever, at a different school,” Obrand said, the corners of his mouth turning up. “She told me the same thing: You can do anything you want as long as you work hard enough.”

While staying up until the early morning to catalog high schools around the country after hours of grading assignments, Obrand eventually inherited much of the Helms Foundation’s collection after it dissolved in 2007, became a member of the Society of American Baseball Research, and brought athletes such as former pitchers Don Newcombe and Dock Ellis to speak in his class.

Now his son David, an attorney in the South Bay, will work to preserve a collection of history that he hopes will stand the test of time.

“I hope the legacy of Rick is that we continue to push, highlight and respect athletics in this district and in every district,” Collins said.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.