Olympic water polo rigors can’t dampen Ashleigh Johnson’s fun-loving spirit

- Share via

The Olympics were never a big deal to Ashleigh Johnson. Anyone who saw her in the pool as a girl – rangy, quick, powerful – knew she had potential as a water polo goalie. They saw glimpses of special talent.

But after a few brief stints with the U.S. junior team, Johnson wanted nothing more to do with the national program.

“It was really boring for me,” she says. “I just wanted to have fun.”

So it seems improbable that five years later Johnson is headed to the 2016 Summer Games as an anchor for the American team and one of the top goalies in the world.

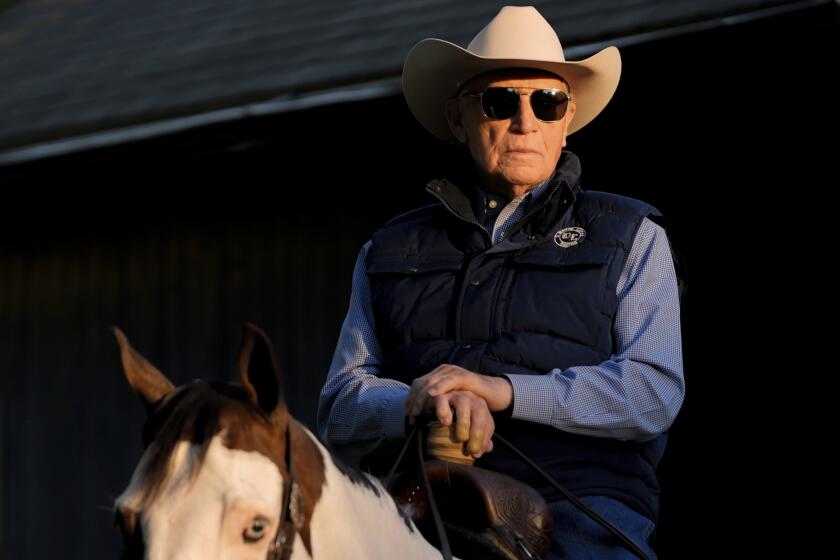

Ashleigh Johnson, a student at Princeton, never dreamt of playing in the Olympic games, but now she is set to play goalie for the USA women’s water polo team.

For most athletes, the trip to Rio de Janeiro represents a lifetime of dreams and hard work. For Johnson, it seems almost accidental.

“That’s kind of how it is,” she says, letting slip a casual smile. “This was never even on my radar.”

Her circuitous Olympic journey began in a community pool near Miami, where she and her sister and three brothers took swimming lessons as kids. After class each day, they fooled around with water polo.

“I loved the competitiveness,” Johnson says. “Especially as a goalie, you get to compete every time the ball is on your side of the pool.”

It wasn’t long before she began playing for a local club and attending youth clinics. U.S. national team coach Adam Krikorian heard about her in a text from one of his former players.

“You wouldn’t believe this girl I found,” he recalls the message saying. “She’s going to be the next superstar.”

There was something extraordinary about the way Johnson moved for her size – she grew to be 6 feet 1 – and the way she covered so much goal with that long wingspan.

The U.S. coaches took note as she led Ransom Everglades High to three state championships, but when they invited her to developmental camps, she bristled at the routine of all practice, no play.

“I was like, ‘Why do I have to do this?’” she recalls. “I wanted water polo to be something relaxing.”

Not many teenagers would turn their back on the U.S. team. Johnson had a similar reaction to college recruiters from traditional programs such as USC and California. To her, Princeton sounded more appealing.

People within the sport predicted that playing on the less-competitive East Coast would stunt her athletic career, but Johnson wanted an Ivy League education and something else.

From the start, she had taken chances in goal, darting out to meet attackers, trying to steal the ball. The coach at Princeton supported developing this instinct, even if it meant sometimes guessing wrong and surrendering the occasional cheap goal.

“Most of the time, Ashleigh can see things in the pool before they happen,” Princeton Coach Luis Nicolao said. “That’s something you can’t teach, so, from the get-go, my philosophy was to stay out of her way.”

In 2013, her freshman season, the Tigers were good enough to sneak into the Top 10 nationally and Johnson made third-team All-American. The national coaches watched from afar.

With long-time U.S. goalie Betsey Armstrong nearing retirement, Krikorian finally picked up the phone and called Johnson.

“I honestly wasn’t sure how she would respond,” he says. “I’d heard she was against doing anything with us.”

Nicolao was already working on Johnson, encouraging her to give the international game a try. She agreed to attend a U.S. camp, but it wasn’t going to be easy.

The national team wasn’t as laissez faire about her playing style. While Johnson characterized it as “pushing the limits,” Krikorian had a different description: “fundamentally unsound.”

The national coach also wondered if Johnson would commit to the rigors of his practices. He worried about her meshing with teammates who had devoted their lives to the game.

That first summer, Johnson recalls, “I felt like an outsider. They definitely told me, ‘You need to take this seriously.’ ”

As time passed, she adjusted to Krikorian’s coaching and began to show a different facet of her personality, treating each practice like a big game, lunging to block shots even after the whistle blew.

“She’s almost shy to show it,” the coach says. “But if you watch her train, she does the little things that athletes won’t do unless they are incredibly competitive.”

Out of the pool, her teammates came to appreciate that quirky attitude and easy grin.

“Focus doesn’t always mean having a stern face,” says Maggie Steffens, a veteran defender. “The thing Ashleigh brings to our team is that happiness, that playfulness.”

Johnson also brought results.

After helping the U.S. to a junior world championship at the end of 2013, she advanced to the senior team the next year and, in 2015, led the Americans to gold medals at the Pan Am Games and the FINA world championships, where she was named top goalkeeper and most valuable player of the gold medal match.

Now, with the Olympics less than three months away, she seems bewildered by her situation, saying: “Every few weeks I have this ‘oh-my-gosh’ moment.”

The 21-year-old insists she is now devoting herself to water polo. Yet she sometimes talks about Rio as if it were a summer vacation, calling it “an experience” and a chance to “meet lots of new people.”

Sports are not the only thing that matter, not with a year of classes remaining to earn a psychology degree, not with a whole lifetime ahead of her.

“I still want balance,” she said. “I still want other things.”

david.wharton@latimes.com

Twitter: @LATimesWharton

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.