Lottery Prize : Ewing Brings Hope to Knicks

- Share via

HEMPSTEAD, N.Y. — On the morning before his first practice as a professional basketball player, Patrick Ewing of the New York Knicks decided to have a little breakfast: scrambled eggs, toast, two glasses of orange juice and fruit. The meal didn’t include coffee but maybe it should have, since the time was 7:30 a.m.

Practice didn’t begin until 10, but, Ewing said, “They told us that the rookies had to get taped first so I wanted to be there early so I wouldn’t get in anyone’s way.”

When the Knicks won the NBA lottery for the right to draft him, did so and then signed him early last month, Patrick Ewing--all 7 feet, 240 pounds--was planted squarely in front of a franchise hurtling into mediocrity.

After a 50-victory season in 1983-84 and a semifinal series that went seven games against the eventual NBA-champion Boston Celtics, the Knicks sold nearly 5,800 season tickets to a public eagerly awaiting the return of excitement to Madison Square Garden. What they got, instead, was chaos as New York players missed a league-record collective total of 329 games because of injury and finished 24-58.

But out of that mess came the Knicks’ berth in the May lottery. In the first week after the Knicks gained the right to the first pick in the draft--which would obviously be the former Georgetown center--they sold 1,000 season tickets. By the time camp opened last Saturday, the total had reached 11,000. Knicks officials estimate that if more seats in the Garden were at or around courtside, the number would have reached 20,000.

At training camp here at Hofstra University, workouts quickly were closed to the public because school officials feared they couldn’t contain the crush. Journalists wishing to attend the practices had to make prior arrangements for credentials, as if covering a playoff game.

Certainly they were there for a major event. Ewing came onto the court shortly after 9:30, clad in blue shorts, and an orange practice jersey--with a gray T-shirt underneath. Perhaps hoping for some sort of identification, forward James Bailey wore a similar T-shirt underneath his jersey. Later in the practice, after working out against Ewing for much of the day, Bailey left the court, went into the locker room--and fainted.

The Knicks expect a similar reaction from opponents. Ewing expects a lot of himself.

“I want to be the best player. I’m gonna try to be the best player I can be,” he said. “Hopefully I’ll be in the same standard, the same level as a Kareem (Abdul-Jabbar), Moses (Malone), or any of the superstars in the NBA.”

Despite his pre-eminent position in the draft and the expectations it has brought, Ewing knows it is just as important to be one of the guys. In reality, being so thoroughly grounded in team play is what helped set him apart in the first place.

“In college I concentrated on helping my team win. That’s what I’m doing now, concentrating on helping my team win,” Ewing said. “I have goals, though. In college I wanted to be the best college center I could be. Now I want to be the best pro center I can be.”

During the first day, Ewing appeared distracted, more intent on assimilating the basics of camp than socializing. Later he got to the point where he could smile and joke with the other players about the miseries of camp.

“Give him about three days, then he’ll be talking up a storm,” said veteran guard Rory Sparrow. “He’s a warm guy, he just has to get accustomed to everything. I think everyone likes him, though, and he likes everyone.”

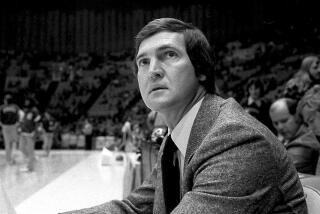

Knicks Coach Hubie Brown says he can tell Ewing is headed in the right direction simply by looking at him. “The people who have the true ability to be superstars, whether in politics, entertainment, coaching, playing, teaching, when they just walk in front of the room there is a certain presence.

“Not everyone has it. But the true superstars, they just seem to have ‘wow,’ you know damn well that there’s something different about this person from everyone else in the room. That’s what that kid has.”

And in exchange for that quality, the Knicks gave Ewing a contract reportedly worth $16 million over six years, although various options and incentives could push those numbers to 10 years and $30 million.

In his first drill on his first day of practice, Ewing made nine of 17 medium-range jumpers (duly noted by each journalist present after a short consultation). During a fast-break drill two hours later, he ran the length of the court quickly enough to catch a speedy guard and slap his shot out of bounds.

Those were the high points. In between, Ewing looked much like any other first-year player. It wasn’t that Ewing had not prepared himself. Each day during the summer, he worked out nearly three hours with former Georgetown players including Eric Floyd, John Duren and Bill Martin. There were also regular workouts with Mike Frazier, who stands 7 feet and weighs 300 pounds.

“I got Mike to bump on me, to get me accustomed to the bigger players,” Ewing said. “After having someone 300 pounds lean on you, everyone else will seem light.”

One thing Ewing might be unable to prepare for is the caustic criticism to which Brown is known to subject players while instilling his system.

“There are certain things we want our players to do every time and we probably do more teaching than other teams to make sure they get it right,” Brown says. “Whenever the other team scores, our guys would be able to tell you who broke down, where and why.”

Brown wasted no time installing a few of the Knicks’ plays, a move that only served to create a sense of hesitancy in the rookies. That manifested itself even in drills, where the players lagged, perhaps not so much from fatigue as trying to do things exactly the right way.

At one point, Brown took the entire squad to task. “You’re dragging!” he screamed. “This is nothing. If you can’t take this, you should pack up and go home.”

Ewing joked later, “I was ready to go.”

But Brown said he didn’t find much lacking in Ewing’s effort.

“What makes him so great? It’s his pride, you can see it in his eyes. It oozes out of him,” said Brown. “What separates the great players from the good in this league is the pounding. It wears everyone down, but the great players get their stats despite getting the most physical beating.

“The other guys show up but they don’t play. They’re sitting out because of this little thing or that one. Patrick isn’t a sitter.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.