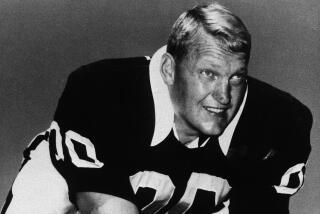

He Could Do Anything but Make the Hall

- Share via

He was probably as good a football player as ever came out of Notre Dame. But he never got a nickname or even a headline. He wasn’t the Fifth Horseman, or the Springfield Rifle or the Golden Boy or Six-Yard Sitko or One-Play O’Brien or even Jumpin’ Joe. Opposition tackles and ends had plenty of names for him, but you couldn’t put them on bubble-gum cards.

Look at it this way: The Notre Dame teams of the late 1940s were probably the greatest college football teams ever assembled. They could have gone intact into the pros. Third-stringers on those teams would have started--maybe starred--on almost any other college team in the land.

They won three of the first four post-war national championships and finished second the other year. They went four years without a defeat. They had five members of the 1947 team on the All-American team and four on the 1946, ’48 and ’49 squads. They didn’t beat people, they buried them. They were so good, the school got embarrassed.

The Detroit Lions of the early 1950s were probably the best pro team of their era. They were the only team that could handle the mighty Cleveland Browns. The Browns were a powerhouse team of stars that had come over from the old All-America Football Conference and would have humiliated the established teams of the National Football League, had it not been for the Lions.

What had these two juggernauts, one college, one pro, the Fighting Irish of Notre Dame and the Lions of Detroit, in common? Well, not much. Or, just enough, depending on your point of view.

First of all, each team had Leon Hart, the mastodonic end who was just easier to tackle than the Washington Monument, which he somewhat resembled. And then, each team had Jim Martin.

You probably never heard of Jim Martin. He’s not even the answer to a trivia question. But, a peculiarity of Jim Martin’s career seems to be that, wherever he went, a national championship went with him.

He was on those great Frank Leahy-coached teams that swept the boards for Notre Dame from ’46 to ’49. Before that, he had been on another championship team, the U.S. Marines in the South Pacific in World War II.

He was drafted in the second round by the Cleveland Browns in 1950, with predictable results. The Browns won the championship that pre-Jim Brown year.

When a back can perform multiple functions in a football game, they call him a triple-threat man. When a lineman can do it, they call him “Hey, you!”

Jim Martin could do anything you needed or wanted on a football field, provided it didn’t require him to touch the football with his hands. He could kick, block, tackle, run. He could play offense or defense with the same degree of skill and enthusiasm.

He played both ways at Notre Dame. On teams that went 38 straight games without a defeat (they were tied twice).

It was as easy as it sounds. There were times when Martin yearned for night landings. The coach at the time at the school of Our Lady was a drillmaster from an old school.

“Coach Leahy wouldn’t let anybody run out of bounds with the football,” Martin remembers. “If anybody fell on the football the way they do today, they’d never play another down of football for him.”

A team that was returning to Notre Dame from service was supposed to be too mature to fall for the religio-emotionalism of college football or accept the hard-nosed discipline that went with it. Leahy soon dispelled that notion. His practice fields were just an extension of boot camp.

“We never called him Frank,” confides Martin. “He was Coach or Mister to you, and you better not forget it. Many years later, I met him at a banquet and I always hankered to call him Frank. He was out of coaching and all, but I couldn’t do it. I leaned forward to say ‘Say, Frank,’ but it stuck in my throat.”

The Detroit Lions of that era would have called the Pope by his first name--or worse. A free-wheeling, hard-drinking, hard-playing cast of brigands, they would have been a pirate crew in another life.

Martin didn’t go direct to this frolicking crew of freebooters. He passed through the crucible of Paul Brown first. Brown was the same kind of cold, contemptuous taskmaster Leahy had been. No players ever called him Paul, either.

“In the (1950) championship game (against the Rams), I was playing defensive end. Lenny Ford had his jaw broken by Pat Harder in an earlier game, and I switched from offensive tackle to defensive end. On this play, I was supposed to hold up Glenn Davis, the running back. But, when I got past my man, I saw (quarterback Bob) Waterfield just standing there. I thought, ‘Uh-oh, I can kill Waterfield!’

“I went for him. He just lobbed this pass to Davis for a touchdown. I had played a great game. Other guys had made mistakes. Marion Motley fumbled on the goal line. Hal Herring, the defensive back, fell down on that play. But Brown traded me to Detroit. For about six or eight players.”

Whatever Brown got wasn’t enough. At Detroit, Jim Martin was six or eight players. “I played guard, tackle, center, linebacker, defensive end. I played on all the special teams--kickoff, kickoff return, punt, field goal.”

Eventually, he even became the team’s kicker. He is the team’s fifth-leading scorer with 259 points, and he kicked two field goals of more than 50 yards in a game against Baltimore in 1960.

A legend in a locker room, if lesser known out of it, Jim Martin today has one regret: “I can understand the Heisman,” he admits. “I can relate to the fact I never made the pro Hall of Fame. But I can never imagine why I was never considered for the college Hall of Fame.”

Neither can anyone who ever watched him play. Maybe he didn’t win enough.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.