How ugly realities yielded a beautiful food memoir

- Share via

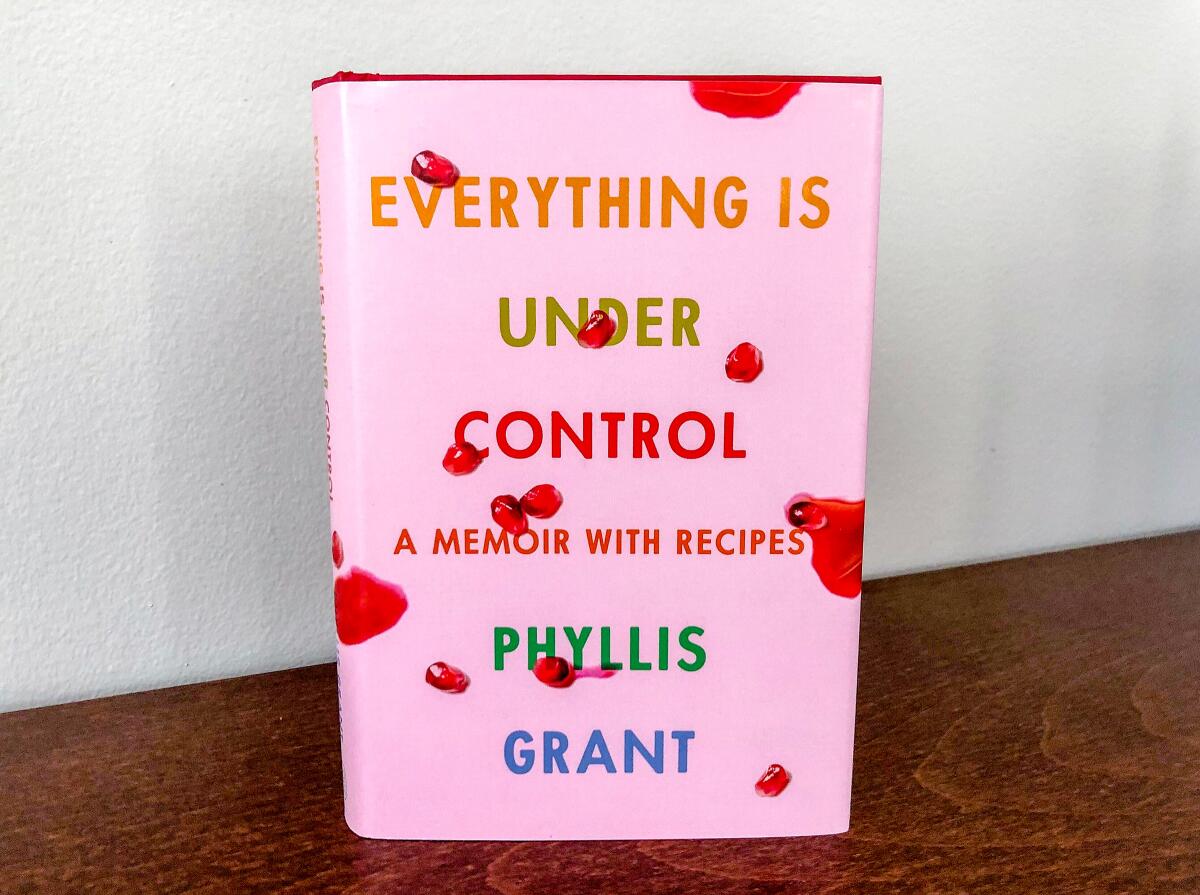

Even if you read most books on a screen these days, take my advice and buy an actual physical copy of Phyllis Grant’s memoir “Everything Is Under Control.” Its words are best absorbed from real pages; some contain only two or three lines. Grant bridges poetry and prose, a span reached through writing that is equally rich and spare. She can reveal whole chapters of her life through a handful of penetrating details.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It’s easy for food writing to veer into flowery realms (guilty hand raised), but Grant excises any superfluousness. She once wrote a now-inactive blog named for her two children, called “Dash and Bella,” and reading through its archives I find the same taut, freely emotive voice. In a 2012 interview in the San Francisco Chronicle, she noted her husband, actor Matt Ross, “keeps the cute out of my writing.”

Beyond the strawberry-ice-cream colored cover, there is no cute in “Everything Is Under Control.” Grant covers great swaths of her life: dance school at Juilliard, difficult childbirth, postpartum depression and family death. In succinct, painfully illuminating stories, she frames her time cooking in some of New York’s best restaurants in the 1990s: “Six months in and I have experienced the obscenely long hours and witnessed the fire hazards, rampant drug use and misogynistic everything. … I still want this more than ever.”

At noon today, Grant will participate in a Zoom event (register here) hosted by Now Serving L.A.; she’ll be in conversation with Jeff Gordinier, food and drinks editor at Esquire.

Grant and I talked this week about writing process, the ugly realities of restaurant kitchen culture and more as we sheltered in place: she in Berkeley, me in Echo Park.

How did you arrive at the spare, poetic structure of this book?

I had a book deal with Clarkson Potter six years ago and ended up writing a very bloated memoir. It went off the rails, but I felt like there were pieces in there to salvage. My editor also left the publisher and no one else stepped up to take on the book, so the deal was broken. I spent three years working with a wonderful freelance editor, Kenzi Wilbur; she and my husband, Matthew, were my two editors.

This is pretty much the nature of the book as it was turned in [to new publisher Farrar, Straus & Giroux]. It’s weird and it’s short. I was always really clear about how I wanted a lot of blank pages. Each section so clearly stood on its own, even if it was two lines about the day we got married and I stood on my tippy-toes to kiss my husband.

Matthew wrote and directed a film called “Captain Fantastic” while I was reworking the book. He was traveling a lot, so I didn’t have a lot of free time at home. If I had five minutes, I would sit with even one sentence and whittle it down. I like to think of it as the cooked-down essence of my life — reduced to the essence of birth, of love, of desire. And of appetite: I think the word doesn’t apply just to food but to dance, to cooking, to movement, to parenting. They shift, too, and this is the story of how those appetites have shifted over my first 50 years.

For a long time, recipes were inserted throughout the book. And photos. But it never flowed. It felt fractured. The white space emerged when we removed the recipes and photos. [The recipes are now the book’s conclusion.] And it felt right. There was room to pause. Take it in.

In the acknowledgements you thank chefs you worked for in the ’90s: Nobu Matsuhisa, Michael McCarty, David Bouley and Bill Yosses. When you detail your time cooking in restaurants, you write about interactions with a chef whose workplace behavior, as you describe it, is clearly inappropriate. You don’t name him specifically. Can you tell me about that decision?

When I was at the Philly Chef Conference in early March I was on a panel with Kwame [Onwuachi] and Jean-Georges [Vongerichten]. Jeff Gordinier, the moderator, asked me if I wanted to name the chef I wrote about. No one had asked me this before. I’m so glad I took a moment — and I really did, it felt like 10 minutes — to think about it in front of a room full of people.

I finally said that it doesn’t matter who the man is. The name doesn’t matter. In the workplace and at parties and on the street, this particular kind of unwanted sexual energy or attention had happened to me hundreds of times. And to my friends hundreds of times, with many, many similar details. It’s more about starting to get that awareness out there. Taking a stand. Never ever putting up with any of this again. It’s a spectrum of behavior. Would I put up with something like this in 2020? No way. But in 1997, I suffered through it and barely questioned it.

We have finally started telling our stories, and prosecuting the predators, and completely restructuring workplace dynamics. In this #MeToo light, I do see that my choice to not name names could be construed as not going far enough. But I played the game back then. I make it clear how very grateful I was to these people for bringing me into their kitchens and for teaching me. I chose to stay, and I learned a lot. Not that I want anyone to shove anything under the rug. And obviously I don’t because it’s all there in my book. I think about my daughter. I want her to read my book. I want her to know that it’s not OK. But I don’t think she would ever put up with what I did. Things have finally started to change.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

How has your relationship to cooking evolved since your time in professional kitchens?

I’m really a calm and confident cook after 17 years of making three meals a day for my kids and my husband. I don’t think I learned to cook in restaurants: I learned how a kitchen works. I learned the politics of that work environment. It takes a few weeks to learn the language, including the body language, and your role there. I was good at absorbing those lessons, and I think that’s why people gave me chances in some of New York’s best restaurants when I had very little experience.

For my family, I learned by repetition — cooking when I was tired, when I was drunk, when I was depressed, when I really didn’t want to. Or I’d use cooking to escape family life, to disappear for hours. It would be 10 at night and my kids wouldn’t have been fed yet.

That said, all I want to do is find my way into the kitchen this afternoon and figure out what we’re eating tonight. It grounds me like nothing else.

Speaking of escape: If you had one recipe to recommend from your book to cook during these insane times, what would it be?

I would say Grandma’s fudgy ice box brownies. I don’t know about you but at weird times of day I’m like, “I really want a Dorito” or “I really want a cold slice of brownie.” They have chocolate chunks in them, and you can dunk it in your coffee or you can have it for breakfast when you’re sad and you don’t want to turn on your phone. They’re best frozen, that’s all I can say.

Have a question for the critics?

Top stories

— Bon Temps and Auburn, two of the best new restaurants to open last year (in the last decade, really), announced they were closing permanently this week. This was the first solo project for Bon Temps’ Lincoln Carson and for Auburn’s Eric Bost, both accomplished chefs.

— Some uplifting content from our cooking duo: Ben Mims has a hot take on the right time to salt a steak, and he brings us the recipe for the brilliant scones baked at Sqirl. Genevieve Ko delivers the secret to a super-easy chocolate soufflé and gives us the blueprint we need for a modern chopped salad. Also, Amy Scattergood reviews the perfect bread handbook for a quarantine baker.

— Patricia Escárcega reports on the complicated and fascinating supply chain of ingredients essential to L.A.’s Oaxacan restaurants, and how the pipeline may be drying up during the shutdown.

— Daniel Hernandez reports on farmers whose livelihoods are endangered by the COVID-19 crisis.

— A persuasive opinion from Kerry Cavanaugh: For restaurants to reopen, L.A. should turn streets into outdoor cafes.

— Finally, Jenn Harris spotlights the chefs we should all be watching cook on Instagram.

— But wait! I also have two new newsletters to recommend. Big news: Ben and Genevieve have a cooking newsletter on the way. And, because food is related to everything, next week brings the debut of Boiling Point, an environmental newsletter about climate in California and beyond. Do sign up.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.