Days of NCAA having it both ways should be nearing an end

- Share via

It was five years ago this month that the landmark Ed O’Bannon v. NCAA antitrust trial took place, bringing hope to former, current and future major college football and men’s basketball players who knew only a world in which their earning power was limited for as long as they were wearing a university’s famed brand and colors.

During those historic three weeks inside the United States Courthouse in downtown Oakland, the NCAA’s business model was laid bare. On the first day of the trial, the NCAA, an organization created by university presidents to represent their best athletic interests, was labeled by an economic expert as a “cartel,” with its members conspiring to fix the price of an athlete’s worth at zero dollars.

The NCAA put forth its arguments as to why its athletes are not employees but rather students who play a sport while at school, similar to a student who pursues theater or music. O’Bannon, the UCLA basketball star and 1995 national champion turned Las Vegas car salesman, sat on the witness stand as the lead plaintiff and face of the movement.

“While you were at UCLA did you think of yourself as a regular student?” Michael Hausfeld, the plaintiffs’ attorney, asked O’Bannon.

“No, not at all,” O’Bannon answered.

“Why not?” Hausfeld said.

“Regular students could do regular things, get a job,” O’Bannon said. “Regular students didn’t have restrictions like an athlete on scholarship did.”

Later that summer, Judge Claudia Ann Wilken sided with the plaintiffs, declaring that the NCAA rule that keeps players from profiting from their name, image and likeness was noncompetitive and therefore an antitrust violation. As a hedge between an all-out free market and the current system, she even offered a plan that each player should have $5,000 each year put into a fund that he could access once he graduates.

At the time, the ruling felt like a huge step forward toward justice for a long-injured class.

But this past week, through two self-serving moves, the NCAA reminded everyone just how much nothing has changed since the summer of 2014.

On Tuesday, the California state Assembly’s Arts, Entertainment, Sports, Tourism and Internet Media Committee passed a bill that would allow college athletes in the state to profit from their name, image and likeness beginning in 2023. While the bill would not allow schools to directly pay athletes, players would be able to receive compensation from outside sources — for example, from a video game company or for signing autographs or memorabilia.

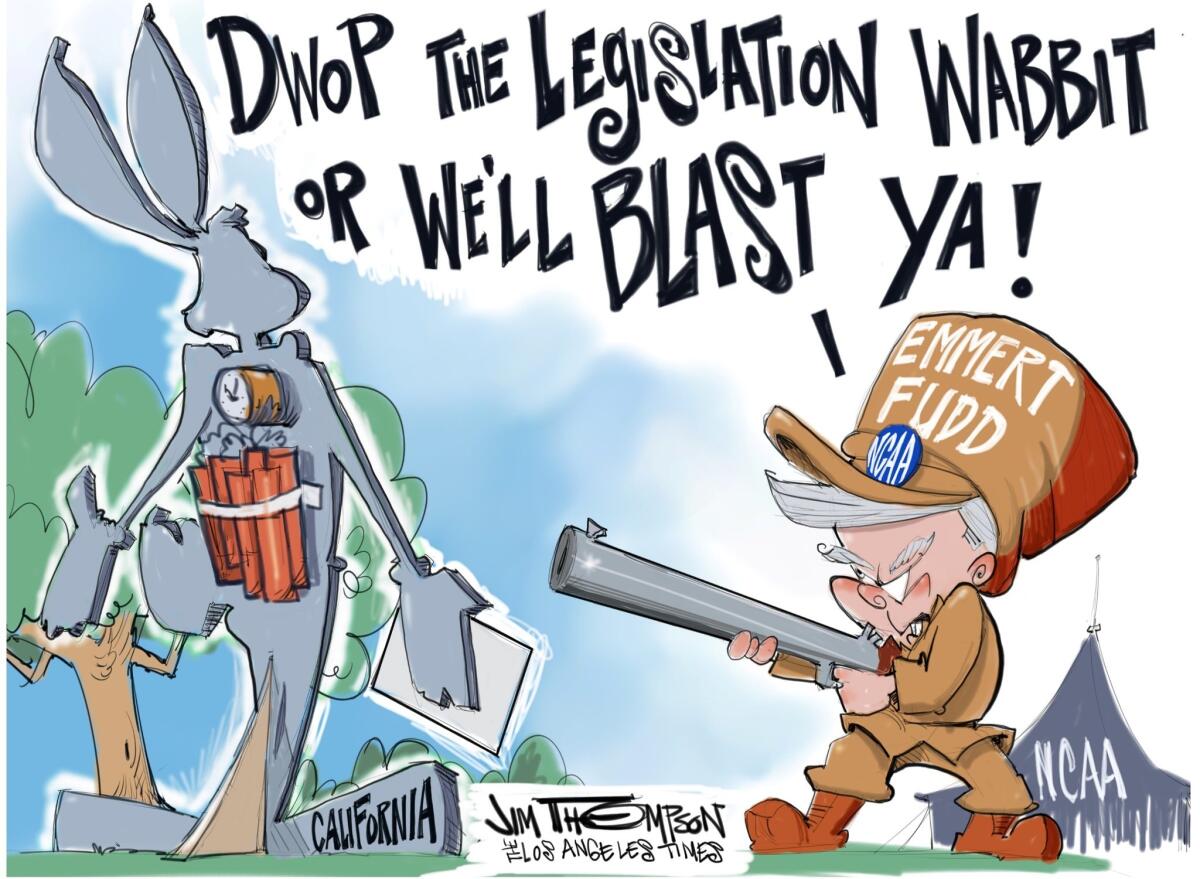

The committee passed the bill despite receiving a letter from NCAA President Mark Emmert, who warned of the dire consequences of it moving forward.

“When contrasted with current NCAA rules, as drafted the bill threatens to alter materially the principles of intercollegiate athletics and create local differences that would make it impossible to host fair national championships,” Emmert wrote.

Of course, he did not consider the idea that the billion-dollar industry he runs needs just that — an altering of principles. Instead, Emmert went on to threaten California schools with NCAA penalties if they were to go along with the bill.

Then on Wednesday, the NCAA announced it has tightened some of the guidelines used to determine when immediate eligibility waivers should be granted to football and men’s basketball players who transfer between schools.

The organization’s rules force players in those sports to sit an entire season if they transfer as an obvious deterrent to the player to seek greener pastures. Yet, athletes in sports that don’t bring in revenue have a one-time pass to transfer freely.

Fourteen months ago, in one of the only player-friendly decisions the NCAA has made in the forum of athlete rights, it decided it would loosen restrictions and allow more transfers to play immediately at their new school if the circumstances the player presented matched up. Predictably, this led to a wave of requests, the NCAA out of habit making up its process as it goes, and now the recent “adjustments.”

This transfer rule is essentially a noncompete clause like a company uses to keep an employee from hopping to a competitor. So the NCAA wants to treat its most valued athletes as employees only when it suits the schools’ agenda.

At the O’Bannon trial, NCAA attorneys argued against the existence of a market for the name, image and likenesses of players. If there was no market for their services, then there could be no antitrust infringement.

Part of their argument was that fans of college football and men’s basketball would watch games, cheer their team on and pack tens of thousands into iconic stadiums and arenas across the country no matter who the players were. As long as there were young men wearing the school colors and as long as those young men were not being paid to play, the NCAA argued, fan interest would be sustained.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

Well, if that were true, then why the fuss about a player transferring in an effort to better his situation?

The NCAA’s corrupt business model is simple: have it both ways. The organization wants all the power that comes with being the boss, the owner, the employer, but none of the responsibilities that are expected in a healthy work environment.

This hypocrisy is the root of what will ultimately bring down the NCAA or force it to change.

If it wants to survive and simultaneously do right by the athletes who fill its coffers, it will allow them to profit from their name, image and likeness. It will increase the meager “full cost of attendance” stipend to better reflect the players’ part in the hundreds of millions of dollars that their games attract in TV revenue.

Only then would a rule penalizing transfers make any sense.

Unfortunately, in seeing what the excitement of the O’Bannon ruling actually led to in the last five years, it is clear college sports fans who want to cheer their teams within a just system will have to hurry up and wait.

Twitter: @BradyMcCollough

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.