There was no deal on DACA or gun control as the revolving door at the White House spun. The year in politics

- Share via

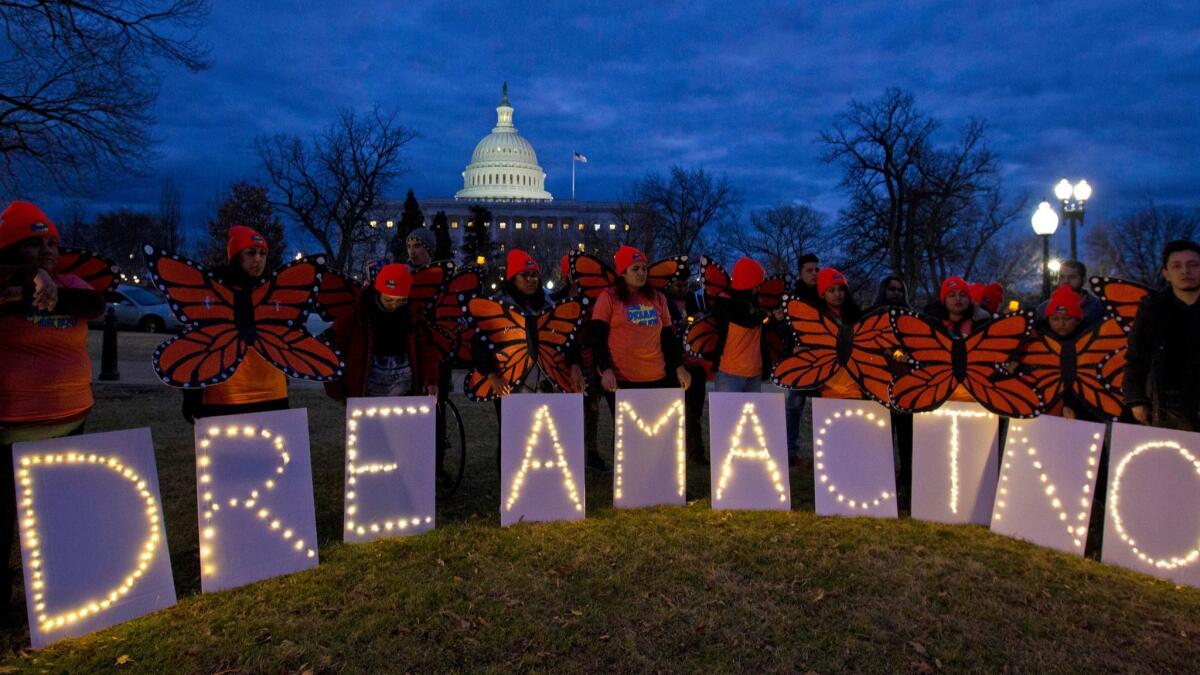

No deal on DACA

During a televised meeting at the White House in January, President Trump urged members of Congress to help the roughly 700,000 U.S. residents who came to the country illegally as children and grew up as Americans. He promised he’d sign a deal, expressing sympathy for the so-called Dreamers even though he had proposed killing Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the Obama-era program that protected them from deportation. But then Trump added demands — calling for $25 billion for a border wall and for restrictions on legal immigration — that Democrats and some Republicans opposed. The president’s credibility suffered when it emerged that he had complained to lawmakers that too many immigrants came from “shithole” countries in Africa and elsewhere. A DACA deal was dead. Federal courts have kept much of the program alive, at least for now, with rulings adverse to the administration.

Futile talk of gun restrictions after Parkland school massacre

After a gunman killed 17 students and teachers and wounded 17 others at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., President Trump held televised “listening sessions” on school safety. Two weeks after the Feb. 14 massacre, he urged Congress to come up with a gun control measure and openly chastised lawmakers of both parties at a White House meeting for not standing up to the National Rifle Assn.’s opposition. He said he would not buckle, only to meet later with NRA executives and adopt their resistance to new legislation. The issue stalled even as students and parents in Parkland and elsewhere pushed for gun controls and began organizing for the midterm election. The White House and Congress took no action despite subsequent mass shootings, including those at a Pittsburgh synagogue and the Borderline Bar and Grill in Thousand Oaks.

Trump fires his top diplomat

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson had served just 14 months when President Trump fired him in March — with a post on Twitter. (He was replaced by CIA Director Mike Pompeo, who was, in turn, replaced by Gina Haspel.) The former Exxon CEO had challenged some of Trump’s foreign policy priorities, including his decisions to withdraw from both the Paris climate accord and the Iran nuclear deal. llerson, who reportedly had described the president as a “moron” after one encounter, left a mixed legacy. An attempt to make the State Department more efficient ran into intense criticism as scores of senior diplomats and others left or were fired, leaving vast gaps. His ouster was hardly unique: Trump also pushed out chief economic advisor Gary Cohn, National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster (he was succeeded by John Bolton), Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt and others in the first few months of 2018. In December, Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis announced he would resign in February, handing the president a strongly worded letter that essentially rebuked him for his military policies and lack of respect for allies. Days later, Trump ousted Mattis from his post two months earlier than planned.

U.S. attacks targets in Syria

Backed by the Britain and France, U.S. warships and planes fired 105 cruise missiles at targets in Syria in April to punish President Bashar Assad’s regime for allegedly using poison gas in the country’s civil war. U.S. officials said chemical bombs had killed at least 43 people in Duma, a rebel-held bastion. The U.S. response targeted three Syrian facilities that the Pentagon said were used to research, produce or stockpile chemical and biological warfare agents. Pentagon officials said the attacks “degraded” but didn’t destroy Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles.

Trump dumps the Iran nuclear deal

After months of denouncing the Iran nuclear accord, on May 8, President Trump announced he was withdrawing from it and would re-impose U.S. economic sanctions on Tehran. The other signatories —England, France, Germany, China and Russia, as well as Iran — said they would continue to honor the 2015 deal, which saw Iran give up its nuclear development program in exchange for easing of international sanctions. Trump later sought to tighten the noose on Tehran by trying to cut off Iran’s oil exports, but the administration was forced to grant waivers to Iran’s six largest customers. Trump has said he wants to cripple Iran’s economy and force the government in Tehran to end support for militant organizations in Yemen, Iraq, Syria and elsewhere.

President upends G-7 summit and other global gatherings

Major international summits normally are carefully scripted and staged. Not in the Trump era. In June, President Trump arrived late at the Group of 7 summit in Quebec, Canada, and left it in acrimony, sending angry tweets against the leaders of France, Canada and the European Union. As he flew away, he withdrew U.S. assent to the traditional closing communique, a first for the world’s most powerful industrialized nations. In July, he insulted the leader of Germany and other close U.S. allies at a NATO summit in Brussels. In November, Trump skipped the annual Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit, sending Vice President Mike Pence instead. Acting at Trump’s direction, Pence took a hard line and — once again — U.S. opposition killed the group’s final communique. Later that month, Trump was relatively restrained at the Group of 20 summit in Buenos Aires, cancelling a planned sit-down with Russian President Vladimir Putin, citing Russia’s seizure of three Ukranian naval vessels and their crews.

Trump meets Kim Jong Un

After months of trading threats and personal insults, President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un clasped hands at an opulent Singapore resort and eased global fears of a nuclear war. The one-day summit between the president and the autocrat, held on June 12, ended with a bizarre U.S. propaganda film that appeared to be aimed at showing Kim the benefits of giving up his nuclear weapons and allowing foreign investment. After the meeting, Trump declared victory, tweeting that “there is no longer a Nuclear Threat from North Korea.” But the vague statement the two leaders signed had no substantive commitments or timeline and the United Nations nuclear watchdog agency said several months later that Kim’s government was continuing to expand its nuclear enrichment and ballistic missile programs.

An acrimonious confirmation process

Justice Anthony Kennedy, a moderate Republican from California, held the deciding vote in some of the most important Supreme Court cases for a generation, including abortion rights and same-sex marriage. On the last day of the 2018 term, he made perhaps the biggest impact of all when he submitted his resignation to the president after 30 years on the court. Trump soon named a more conservative replacement — Brett Kavanaugh, a Washington insider who did not contain his contempt for liberals and Democrats during his confirmation hearing, a process that was roiled by accusations of sexual assault. Palo Alto University professor Christine Blasey Ford’s accusation that Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her when they were teenagers brought the #MeToo movement to Washington in painful detail. The Senate Judiciary Committee conducted a nationally televised hearing to investigate the claims, which Kavanaugh vehemently and tearfully denied. The full Senate confirmed Kavanaugh in October by a 50-48 vote, one of the slimmest margins for a Supreme Court nominee in U.S. history.

Mueller indicts Russians for meddling in 2016 election

In July, special counsel Robert S. Mueller III produced a criminal indictment that cut to the core of the Kremlin’s support for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election — and Trump’s subsequent denials that it occurred. A dozen Russian military intelligence officers were charged with hacking the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton’s presidential operation and releasing the emails to WikiLeaks, crimes that rattled the Democratic nominee’s campaign during crucial moments. The detailed 29-page indictment tracked how Russian officers built backdoors into Democrats’ computers, tricked them into divulging their passwords and unleashed chaos. Mueller had obtained a related indictment in February against 13 other Russians for using social media and other tools to undermine the U.S. election. Eight other individuals have been charged or pleaded guilty in the Mueller probe, but none for directly cooperating with the Russian operation.

Trump meets with Putin in Helsinki

After meeting privately for more than two hours with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, Finland, in July, President Trump said he believed Putin over U.S. intelligence officials and two detailed grand jury indictments when it came to the Kremlin’s involvement in the 2016 election. “He just said it’s not Russia,” Trump told reporters. “I don’t see any reason why it would be.” An immediate and bipartisan uproar — former CIA Director John Brennan called it “treasonous” — forced Trump to backtrack a day later and say he had misspoken. The Helsinki news conference, in which Trump again criticized the special counsel investigation as a “witch hunt,” only led to more questions about the president’s support for Putin and a drop in his approval ratings.

A one-two punch for the president

First, a federal jury in Virginia convicted Paul Manafort, President Trump’s former campaign manager, of eight counts of fraud, tax evasion and other charges in a massive criminal scheme that extended through the 2016 campaign. Moments later, Michael Cohen, Trump’s longtime personal lawyer and fixer, delivered a more dangerous blow to his former boss in a federal courtroom in New York. While pleading guilty to eight counts of tax evasion and bank fraud, Cohen implicated the president in a crime by saying Trump had approved hush money payments to two women — Stormy Daniels and Karen McDougal — in an effort to influence the 2016 election. Both women claimed they had sexual relations with Trump years ago, which he denied. Cohen doubled down in November, pleading guilty in Washington to lying to Congress about Trump’s efforts to build a hotel and condominium complex in Moscow for eight months after he announced his White House bid. The bombshell case marked the first time the special counsel’s investigation had touched upon Trump’s business interests. (In late November, the office of special counsel Robert S. Mueller III said, in a court filing, that Manafort had lied — repeatedly — to prosecutors in violation of a plea agreement he'd signed to avoid a second trial. )

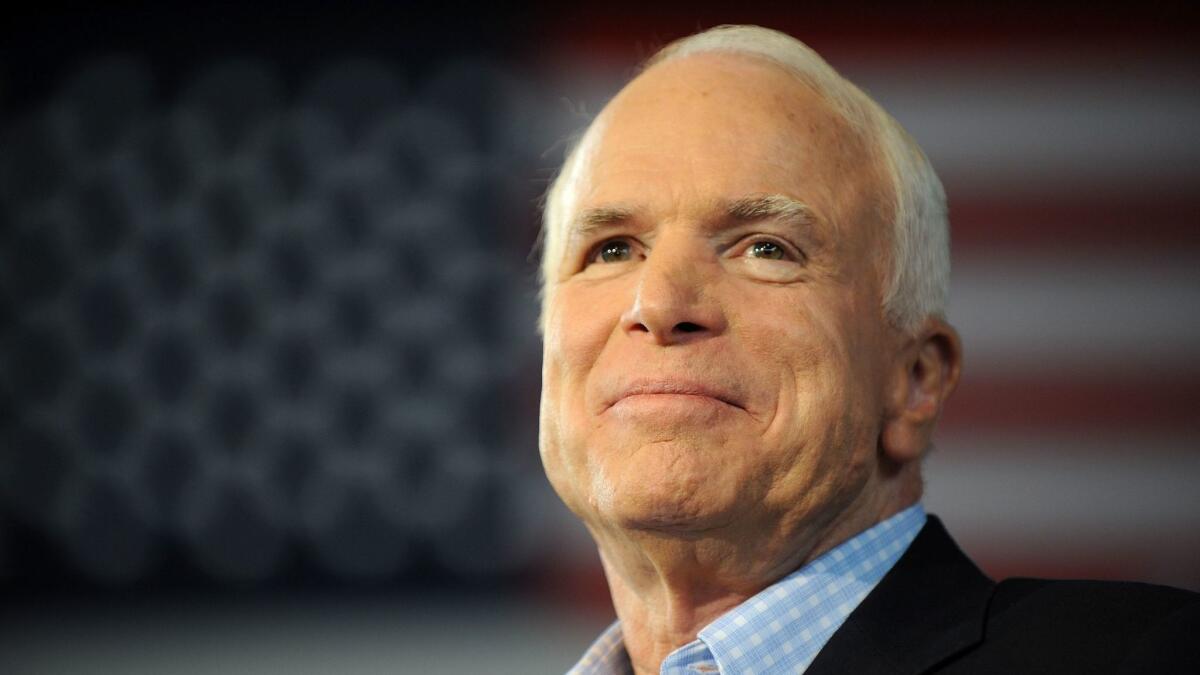

John McCain dies

President Trump never apologized for saying during his presidential campaign that John McCain, who was tortured and imprisoned for five years after his Navy plane was shot down in Vietnam, was not a war hero because he was a prisoner of war. McCain went on to become a six-term U.S. senator from Arizona, the Republican presidential nominee in 2008, and to many, a conscience on Capitol Hill. After his death in August, McCain lay in state at the United States Capitol Rotunda, and his funeral was televised from the Washington National Cathedral. All of official Washington attended and former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama gave emotional eulogies. The president stayed away at the McCain family’s request.

Journalist killed in Saudi consulate; president defends Saudi allies

Jamal Khashoggi was a complicated figure, an erudite Saudi journalist who had close ties to the Saudi royal family but then broke with them. He moved to Virginia and was writing a column for The Washington Post when he traveled to the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, to obtain documents he needed to marry. He entered the building on Oct. 2 but never came out alive. Turkish officials said Khashoggi was strangled and cut up with a saw. The CIA concluded that the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, most likely had approved the murder. Trump disagreed, saying “maybe he did, maybe he didn’t,” and refused to sanction Saudi Arabia for killing a legal U.S. resident, saying U.S. weapons sales to Riyadh were more important.

Military sent to Southwest border

In October, the White House ordered about 5,800 active duty Marines and Army troops to the border with Mexico, claiming they were needed to help the Border Patrol block thousands of Central American migrants from entering the country. President Trump characterized approaching civilian caravans as a looming “invasion” and falsely claimed it included terrorists and was organized by Democrats. Critics accused him of using the Pentagon as a political prop and exaggerating the threat to fire up supporters a week before the Nov. 6 midterm election. The troops initially installed razor wire and barriers near crossing points, but after several weeks the White House expanded their role to include use of deadly force if necessary.

Suspicious packages, panic and an arrest

The packages, with suspicious, potentially explosive devices, were sent to Financier George Soros, Sens. Kamala Harris and Cory Booker, former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, Hillary Clinton, former President Obama, former Vice President Joe Biden and Robert De Niro, among others. The mailings spread waves of fear among politicians and media figures a couple of weeks before the midterm election. A few days after the first one was discovered, a suspect, Cesar Altieri Sayoc Jr., 56, was taken into custody in Florida and charged with five federal crimes, including interstate transportation of an explosive and threatening a former president.

Democrats take the House

A “blue wave” propelled Democrats to recapture control of the House in November’s midterm elections, led by suburban women frustrated with President Trump’s policies and behavior. In all, Democrats netted 40 seats, far more than the 23 they needed. Come January, Democrats will lead several House committees – including intelligence, judiciary and oversight – that are expected to investigate Trump’s business affairs and other sensitive issues. The new Democratic majority also wants to push legislative priorities such as infrastructure projects and reducing healthcare costs — although they must deal with a Republican-backed Senate that has its own agenda.

Obamacare wins big in the midterms

The midterm election is likely to be recognized as the moment that cemented the Affordable Care Act’s place alongside other pillars of the American healthcare system, such as Medicare. Most immediately, the Democratic takeover of the House of Representatives precludes any new Republican campaign to repeal the law. More profoundly, the elections revealed the depth of public support — in red states and blue — for core parts of the 2010 law, including Medicaid expansion and protections for Americans with pre-existing medical conditions.

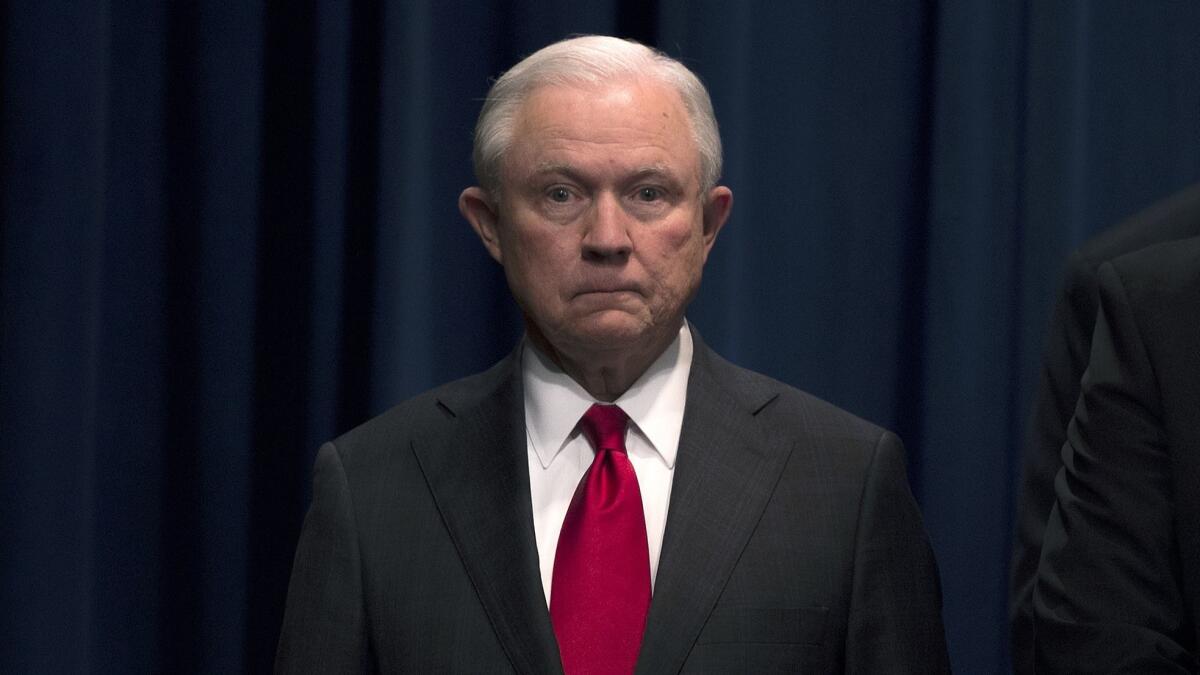

Sessions gets the boot

For more than a year, President Trump had mocked, taunted and criticized Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions. The president had never forgiven Sessions, a former four-term conservative senator from Alabama, for recusing himself from overseeing the Russia investigation because he had been deeply involved in Trump’s presidential campaign. In angry tweets and cruel comments, Trump described Sessions as “beleaguered,” “VERY weak” and “DISGRACEFUL,” insults Sessions mostly endured in silence. He finally forced Sessions out the day after the midterm election — and named an avowed political loyalist, Matthew Whitaker, as acting attorney general. Whitaker said he would assume oversight of the special counsel investigation, a prospect that raised concerns that he might act to block its work.

Nov. 30 – George H.W. Bush dies

George H.W. Bush, the 41st president of the United States and the father of the 43rd, died Nov. 30 at his home in Houston at the age of 94. He was the last World War II veteran to serve as president, but his broader legacy was as a statesman who helped guide an anxious nation — and the world — out of the Cold War without firing a shot. As president, he took America to war to push Iraqi troops out of Kuwait, helped reunite Germany after the Berlin Wall tumbled and declared a “new world order” after the Soviet Union collapsed, leaving the United States as the only global superpower. But he was less surefooted in domestic politics, especially after the economy stumbled, and he lost the White House after only one term. He is remembered as much for his personal modesty and ethics as his political achievements, a clear contrast to today’s political schisms and harsh rhetoric.

Read More: The Year in Review »

Here are our most read, shared and retweeted stories of 2018 »

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.