Home Boy Still Humble, Enthusiastic After Year in NBA

- Share via

At 8 a.m., invading a Belmont Shore beach occupied only by a tractor, Morlon Wiley raced through deep sand with the enthusiasm that defines him. In seconds, he became a speck on the gray horizon.

Returning to the parking lot after that workout last Saturday, Wiley, 22, entered not a luxury car befitting a pro basketball player but a 1966 Volkswagen black bug he has owned since he was a sophomore at Cal State Long Beach.

“Eventually,” he answered with his easy smile when asked if a Mercedes-Benz is in his future. Typically, he added, “I’ll get my mom one first.”

He always credited her with keeping him humble.

Wiley, who as a senior led the 49ers to a 17-12 season record and a National Invitation Tournament appearance two years ago, was a 6-foot-4 rookie guard for the Dallas Mavericks of the NBA last season.

Unprotected by Dallas in the recent expansion draft, he was selected by the Orlando Magic and expects to sign with that new team today. His agent, Leonard Armato of Los Angeles, said he anticipates a guaranteed contract calling for “significantly more” than the $100,000 Wiley made last season.

For the summer, Wiley has returned to the town in which he grew up, staying in a campus dormitory to be near the gym and weightlifting room, and helping 49er Coach Joe Harrington conduct clinics.

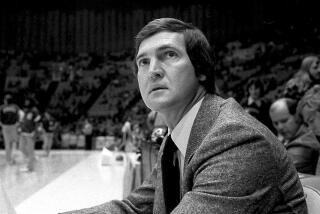

Although he played an average of only eight minutes in 51 games with Dallas, Wiley impressed Mavericks Coach John MacLeod, especially as a person.

“A great young man, a breath of fresh air,” MacLeod said by telephone from Dallas. “We hated to lose him, we really wanted to keep him. I think he’ll be a very good player. He has confidence in his ability, is respectful of others and is one hellacious competitor.”

The first draft pick (second round) of the Mavericks in 1988, Wiley was on a team with three established guards--Rolando Blackman, Derek Harper and Brad Davis--so the recognition he resolutely sought did not come easily. Although fans might recognize him in a Dallas mall, his national TV time was minimal and Lakers broadcaster Chick Hearn called him Morton Wiley.

“I showed a lot of enthusiasm,” Wiley said, wearing a sweat suit with a Mavericks insignia during a break in his morning run-lift-shoot routine. “I let people know I wanted to be there. I’d have to humble myself and do what I could. I would sometimes get in a game with only 20 seconds left, but I would think, ‘I might get a steal or a rebound.’ ”

A quick, defensive-oriented player, Wiley had to work hard just to make the team. On the advice of his brother, Michael, a former NBA player, he did not look at newspapers when he was trying out so he would not have to read that he might be cut. What his mother, Geraldine, had to say was also held dear.

“My mom said to remember that whatever happened her love was still going to be there,” Wiley said. “That got me over the hump. I knew I had nothing to lose. I saw myself playing in the league; it was just a matter of getting my chance.”

His first year as a pro was similar to his junior year at Long Beach Poly High School, when he played little but was named the most spirited team member. Last season, he again sat on the bench and cheered, staying ready, waiting his turn.

“My attitude was great the whole time,” said Wiley, who would arrive hours early for home games, dressed in practice clothes. “I’d get my workout in regardless of whether I played or not.”

On the road, besides acquiring tastes for good restaurants and various cuisines, he became familiar with the health clubs and local gyms, spending long hours in them. He became a frequent writer of letters, and sent a touching one to the CSULB coaches (see accompanying box). “It was such a great letter to get,” Harrington said. “Here’s a guy who made it to the big time and he took the time to remember where he came from and say thank you.”

Wiley’s character made an impact on the big names of his sport.

“People are the same, human beings,” he said. “They treat you with utmost respect if you’re a good person. The superstars would talk to me--Magic Johnson and Kareem (Abdul-Jabbar) would tell me what I was doing wrong, Kevin Johnson (of Phoenix) would take me out to dinner, Mark Aguirre gave me four or five suits. They appreciated a young guy who worked hard. I looked at them as regular people, not as superstars, and they respected me for that.”

He loves the pro life--”red carpet all the way, the best hotels”--but has seen that it invites abuse by young men with wealth and idle time. “Some guys can’t handle it,” he said. “I live a basic life, one without a lot of risks. I don’t do drugs or drink, I have good clean fun, going to dinner, spreading my name around.”

Among those who befriended Wiley was teammate Roy Tarpley, who entered a drug rehabilitation center during the season. “He took me in when I got there, he was very supportive,” Wiley said, adding that Tarpley never drank or used drugs in his presence.

In appreciation, Wiley bought Tarpley a pool table.

“It was unfortunate he slipped,” Wiley said. “I just pray for him.”

Money has not become an obsession with the young man who was raised in Long Beach’s inner city. “Adrian Dantley told me it’s not how much you make, it’s how much you keep,” Wiley said, referring to the forward who moved to Dallas in a trade with Detroit. “That stuck with me. I saved quite a bit.”

“People say I’m cheap,” he went on with a laugh. “I’d rather see my mom have it. She raised five kids, and hasn’t asked me for a cent.”

The last season was one he will not soon forget. He lived on his own for the first time, accepting the responsibilities brought by bills and dirty dishes; he saw how a team was affected by a major trade (Aguirre for Dantley) and by drugs, and felt the pressure of a fight, which turned out unsuccessful, to make the playoffs.

“Rolando Blackman told me that it was good I saw all that because now nothing should faze me.”

Wiley is proud that he has broadened what he calls his level of awareness. “I was doing things (in college) the same way all the time--always eating pizza, going to the same gym, because I didn’t know better. Now I’m not afraid to take a chance. I want to see different things, I want to grow.”

He regrets leaving Dallas and MacLeod. “He would talk to me all the time,” Wiley said of his former coach. “He’d come over at dinner and we’d talk about basketball and life. I’ll miss the talks we had. But he made a decision to play certain guys and stuck with it. I didn’t want to leave but change is inevitable.”

Wiley is optimistic about his chances with Orlando, where his back-court competition will include veterans Reggie Theus, Scott Skiles and Sam Vincent.

Bob Weiss, a Dallas broadcaster last season and now an assistant coach with the Magic, said Wiley, who averaged 20 points in his last season at Cal State Long Beach, “never got his offensive game going” with the Mavericks. “Although everyone’s high on him, we don’t really know for sure about him,” Weiss said. “We’re anxious to get him in our summer camp.”

Last week, as Wiley drank a soft drink in a campus deli where the employees wondered if he was someone famous, he seemed anxious to get back to the life he has fallen in love with.

He talked about someday returning to school to acquire the additional credits needed for his degree, but that will have to wait. What he has now, he said, a basketball under his arm, is “the best job in the world.”

Letter to Ex-Coaches

Morlon Wiley wrote this letter to the Cal State Long Beach basketball coaching staff last October, shortly after he joined the Dallas Mavericks.

Dear Coaching Staff:

I want to take the opportunity to thank you for all the wonderful things you’ve done for me and my family this past year.

You were not only interested in my athletic ability but you also showed concern for me as a person.

You showed praise for my effort, confidence in my leadership abilities and comfort in my time of need.

You can add me to the list of people that believe the harder you work the luckier you get.

Thanks a million, and keep up the good work. Morlon Wiley

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.