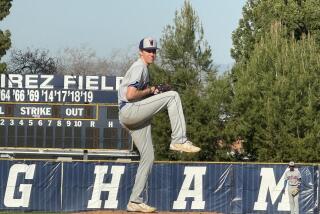

Younger Cey Has Inherited Aptitude for Family Business : High school baseball: El Camino Real shortstop is considered among the best in the nation at his position.

- Share via

Talk to the father, and the answer is predictable. It’s in his blood, dad says. In his genes. The boy was born to play.

It was obvious. The kid always had an affinity for the game, a feel for the fundamentals, even when he was a rug rat.

The kid was 5 or 6 years old when mom realized dad was right. According to family lore, the kid had spent the spring morning hobnobbing with the big leaguers when game time approached.

As father prepared to waddle to his customary spot at third base, mother and son found their seats behind the backstop. The Florida sun beat down on Holman Stadium as the words to the national anthem blared forth: “Oh, Cey can you see?”

The kid liked that part, and, boy, could he see. What’s more, he understood.

His mother suggested to the squirrelly tot that he might want to sit down and begin learning about the sport. He long had rubbed elbows with major leaguers, she said, and perhaps now it was time to absorb the game itself.

The talkative youngster rolled his eyes and responded, in essence: “You mean, like when there are runners on first and second, the batter hits the ball to the shortstop, he steps on the bag for the first out, then throws over to the first baseman to complete the double play?”

The kid beamed. Mom didn’t question his baseball knowledge again. Yup, Ron Cey is definitely right. The kid has a feel for the game.

“Early on, I was just fascinated with it,” the kid said. “It was always, I don’t know, the good part of the day. “

If things work out like Daniel Cey hopes, it could last the better part of a lifetime.

Cey stood at the head of the class at El Camino Real High last month and wasn’t especially surprised by the student response. Individuals had been asked to stand and speak about themselves, and classmates, in turn, were required to give their impression of the speaker.

“Three people said, ‘I get the impression that you’re arrogant and cocky,’ ” Cey recalled.

Arrogant and cocky? Cey, a senior shortstop, turned quite a double play. Cey didn’t really bristle at the news, though he prefers to be called “confident.”

“You have to be that way in baseball if you want to succeed,” Cey said. “I’m never exactly satisfied with everything, because if you’re satisfied you don’t progress.

“You have to set a standard, and when you reach it, you set another. When you stop, you’re at the end of the line.

“Time for another occupation.”

Ron Cey punched a big-league clock for 17 years, hit 316 home runs and is generally considered the best third baseman in Dodger history. He was released by the Oakland A’s in 1987, but baseball was not in Ron’s rear-view mirror. More like in his viewfinder.

Life away from the majors finally gave the elder Cey a chance to watch his son play. And for dad, big-league credentials or not, that meant all the obligatory Little League trappings.

“When he came back, he got caught up in it,” Dan said. “He’d never really seen me play. He filmed all the games. He stood out in center field, taped the game and narrated it.”

Ron, 45, hasn’t missed many of his son’s games since, though unless people seek him out, he is easily overlooked. Dad keeps a low profile. Never is heard a discouraging word.

“Other parents are running around going, ‘Why isn’t my kid hitting fourth?’ ” said Dan, considered one of the nation’s best shortstops. “(It’s) because he’s not good enough to hit fourth.

“Parents put too much pressure on their kids because their expectations are too high.

“We have a good relationship, a real good relationship. He’s the guy I learned everything from. I’ve never gone to a batting coach, never been to a summer camp for baseball, never have to go to the batting cages.”

To be sure, Dan learned the game at the highest level. He knows every corner of Dodger Stadium, has shagged fly balls at Wrigley Field and at one time or another, pestered just about every big-name player from the 1980s.

Dan followed Oakland rookie Mark McGwire around like a shadow. He sat on Cub shortstop Shawon Dunston’s knee. Dunston liked the kid so much, he gave him a glove. Souvenirs piled up.

Dan has enough baseball memorabilia to fill a large bedroom, if not finance a small house. Autographed pictures, bats, ball and posters. Stacks of baseball cards so valuable that when he needs “petty cash,” he sells a few.

“His room is a shrine to baseball,” said Don Hornback, Dan’s American Legion coach. “It’s like any ballplayer’s room, but his collection is more extensive because he had access to better stuff.”

In the bat rack alone are wooden implements of destruction signed by guys named Canseco, McGwire, Gwynn and Griffey Jr.

“If my room blew up, I’d be in a lot of trouble,” Cey said. “I’d be hurting.”

Cey, a contact hitter who sprays the ball to all fields, hurts the opposition with more than his bat. Last season, according to Coach Mike Maio, Cey made only one error at shortstop.

“The thing he has on me is defensive skill,” Ron said. “With the glove, he’s light-years ahead of me at that age.”

With respect to power statistics and physical development, Dan was light-years--and light pounds and light a few inches--in his dad’s dust. Ron was an early bloomer, Dan a 97-pound weakling.

“You could have kicked sand in his face at the beach and had your way with him,” said Ron, who was concerned about Dan’s size.

Dan weighed 97 pounds and stood 5 foot 2 when he enrolled at El Camino Real as a freshman. When he took the field, all fans could see were shoes and a hat. He spent his freshman season on the junior varsity.

He grew about six inches in the next few months and he hasn’t stopped. Cey now stands 6 feet tall and weighs 160 pounds. Think Ron was worried before? His wife, Fran, has plunked down $500 four times in four years to buy dress suits that Dan keeps outgrowing.

Last month, the Ceys were invited to the wedding of former Canoga Park High and UCLA standout Adam Schulhofer. Trouble was, Dan already had outgrown his new suit, so Fran Cey borrowed one from Schulhofer’s mom.

“I saw (Schulhofer) at the wedding and he said, ‘Hey, that’s my jacket,’ ” Dan said. “It fit. Hey, what could I say?”

The Cey hey kid made the varsity as a sophomore but was told by Maio that the shortstop position was spoken for. Gregg Sheren, in fact, earned All-City Section honors later that year. Dan would have to try his hand at second base if he wanted to play. Dan went home and gave the news to Ron.

“ ‘Dad, I really want to do this,’ ” Dan said, recalling the cajoling that took place. “So he called up his buddy to come out and show me how to play the position.”

Ron called no second-banana second baseman. There, on the El Camino Real field, Davey Lopes taught Dan--who batted .360 with seven doubles in the leadoff position--how to play second.

Dan, who will turn 18 in November, has embarked down a well-marked familial trail. His father played for two seasons at Washington State before he was drafted by the Dodgers, the team for which he played 12 big-league seasons. Dan signed an NCAA letter of intent last fall with Cal.

Of course, the family highway could have some world-class potholes. Big names carry high expectations. Ron’s siblings often groused about being routinely referred to as brother or sister of Dodger All-Star. . . . Ron’s brother Doug, 10 years his junior, also played baseball at Washington State. “Baseball didn’t work out for (Doug),” Ron said.

When Dan made the El Camino Real varsity two years ago as a sophomore, his identity always seemed tied to his father. After a while, it got on Dan’s nerves. Cey batted .418 last season, drove in 16 runs and was an All-City 4-A Division and Times All-Valley selection. Yet when he opened the morning paper last spring, after two years on the varsity, it often was the same old thing.

“Even in the (highlights), it said, ‘Dan Cey, son of former major leaguer Ron Cey, hit a home run.’

“That was it. I don’t see the reason for doing that. It was my only homer of the year. What’s the point? I hit the homer.”

An uncommon talent, set off by commas. The younger Cey figures he must carve his own niche.

Unless somebody asks Dan about his father, the subject is rarely broached.

“I don’t bring it up,” Dan said. “If I’m going out with a bunch of people and one person says, ‘Come meet my friend Dan, his dad is Ron Cey,’ then that person will not be my friend any more.

“What is the point of that second person knowing who my dad is? They aren’t going to meet him. They need to judge me based on who I am.”

Yet, one facet of Dan’s character is inextricably tied to his father, and Dan doesn’t mind a bit.

“It has to do with self-esteem,” Dan said. “You have to think that you’re good, think that you can do things right and that you aren’t going to fail.”

Confidence is more than a common thread between the Ceys.

“There’s a lot of spit and vinegar in Daniel,” Hornback said, laughing. “He’s definitely no shrinking violet.”

Why should he be?

“He’s seen some of the greatest players in baseball at a very early age,” Ron said. “Why would he be anything but confident when he played pepper, shagged fly balls and ran to get coffee for some of the best to play the game?”

“Yeah, he’s pretty comfortable with the game.”

It fits, well, like a glove.

“When I grew up watching my dad play, I said, ‘This is what I want to do,’ ” Dan said. “Those guys looked like they were having so much fun. They were getting paid to play baseball.

“What more can you ask for?”

CITY SECTION PREVIEWS: C10

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.