Pillowcase masks and trash-bag gowns. The bleak, deadly reality in California nursing homes

- Share via

The masks are long gone, replaced by face covers fashioned from pillowcases. Cleaning supplies are dwindling. And when Maria Cecilia Lim, a licensed vocational nurse at an Orange County nursing home, needs a sterile gown, she reaches for a raincoat bought off the rack by desperate co-workers.

“This is just one raincoat that we have to keep reusing,” Lim said last week between shifts at the Healthcare Center of Orange County, a 100-bed nursing facility in Buena Park. “A lot of people are using it.”

In thousands of facilities that house California’s elderly and infirm, this escalating scarcity driven by the spread of the coronavirus is forcing nurses and medical assistants on the front lines to employ creativity and pluck to combat a deadly pandemic.

These are some of the unusual new scenes across the Southland during the coronavirus outbreak.

Nursing homes and assisted living centers are fast becoming a locus of outbreaks, driving up mortality rates and straining public health resources.

Yet institutions and public health officials said shortages abound: of protective gear, testing kits and, increasingly, of staff, who are sick or afraid to show up to work. With family visits halted, workers — many of whom shuttle between multiple facilities — are a potential source of infection in nursing homes but are essential to feeding, bathing and caring for the state’s vast aging population.

Last week, a surreal tableau played out in Riverside, where 83 patients were evacuated, many wheeled out on stretchers. Five employees and 34 patients at the Magnolia Rehabilitation and Nursing Center had tested positive for COVID-19, and when other scared workers stopped showing up for shifts, the crisis led to a swift removal of residents.

“That was not sustainable,” said Jose Arballo Jr., spokesman for the Riverside County Department of Public Health.

Though the spread of the novel coronavirus in California has been slower than hot spots in New York, Michigan and Italy, allowing hospitals here to prepare for the long-feared surge, there’s a different reality inside institutional care facilities, where elderly residents, many with underlying medical conditions, are exceptionally vulnerable.

In Pasadena, for example, all seven of those who have died of COVID-19 lived or worked in long-term care homes.

“This is an infectious disease that moves quickly,” said Matt Feaster, the epidemiologist for the Pasadena Public Health Department who is leading the city’s response to confirmed cases at nine residential care facilities. “A small problem can become a big problem.”

Dotting the state are nursing homes where the deadly contagion has taken hold. In San Bernardino County, at least 25 people have died, about half of them residents of nursing homes and assisted living facilities. At least 94 confirmed cases came from a single facility in Yucaipa where 10 residents have died.

Four people have died and 38 others have tested positive for the virus at the Kensington assisted living facility in Redondo Beach.

More outbreaks have been reported in Orinda, San Jose, Burlingame and San Francisco. At a care center in Hayward, 49 staffers and residents tested positive, Alameda County officials said.

At least 1,266 residents and staff members at the state’s more than 1,200 skilled nursing facilities have confirmed cases, Gov. Gavin Newsom said Friday. Nearly 400 in residential care facilities also have COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. The actual number is probably higher.

Nationally, outbreaks in nursing homes and assisted living centers have propelled the crisis. Long-term care facilities have accounted for at least 221 deaths in Washington, or about half of the deaths in the state. In New York, more than half of nursing homes have positive cases, and more than 1,700 people in such facilities, about a third of nursing home residents with COVID-19, have died.

The situation has at times resulted in drastic measures. In New Jersey, where more than 3,300 people in institutional care have tested positive, 10 deaths in a veterans’ home prompted officials to send 40 National Guard medics to bolster staffing levels.

At hospitals and emergency rooms, proof of the coronavirus’ devastating effects in homes for the aging is apparent.

“The speed at which our elderly patients go into respiratory failure is staggering,” said Sydnie Boylan, a registered nurse at Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center. “The patients go downhill so quickly, and once they go on a ventilator, most of them don’t come off.”

Dr. Nick Kwan, assistant medical director of the emergency room at Alhambra Hospital, agreed that among the sickest were those from nursing homes. He said it did not bode well.

“If there is a surge, you are talking about the 50- to 100-bed nursing homes,” Kwan said. “These patients are going to be very sick.”

With most facilities essentially on lockdown — ending family visits and new admissions — focus has turned to the staff, the one group that circulates through a nursing home, sometimes several.

“Many are afraid,” said April Verrett, president of the Service Employees International Union Local 2015, which represents some 20,000 nursing home employees across the state. “But what I hear more than anything is that our folks are continuing to go to work.”

Before the pandemic, Verrett said, workers often used N95 masks once and then tossed them out. The advice now, she said, is, “Hold on to it for your dear life, clean it every day.”

With the usual supply chain upended, owners of nursing homes have made trips to Sally Beauty Supply and AutoZone, with mixed luck, Verrett said. One facility that ran out of plastic sleeves to cover the thermometer improvised by using sandwich bags.

“Everyone is anxious,” said a certified nursing assistant at a South Pasadena nursing home. Her concerns centered on colleagues who work at multiple facilities, scraping by at $14 or $15 an hour. Her boss has begun scrutinizing their employment lest they inadvertently bring the virus with them.

“We do not make enough with just one job,” she said. “You need a good two full-time jobs, working seven days a week.”

Dr. Ying-Ying Goh, Pasadena’s director of public health, said some facilities have had difficulty securing thermometers, which are used to screen employees before, during and after their shifts.

“There’s a backlog in thermometers,” Goh said. “That’s a problem.”

Lim, who works at the nursing home in Orange County, said she was “lucky” because family members had sent her a few surgical masks. She wears one of those under her cloth mask, which is sewn from a cut-up pillowcase. Every night, she said, she washes both the surgical mask and the repurposed pillow case and “sterilizes both by ironing them.”

In lieu of sterile isolation gowns, staffers at the Los Angeles Jewish Home for the Aging are sewing sleeves onto the cloth garments typically used by patients. Underneath, workers don a trash bag for heightened protection.

“Can you imagine that clinicians have to wear trash bags in order to provide care to the greatest generation in the history of our time? It’s just unreasonable,” said Dr. Noah Marco, chief medical officer for the L.A. Jewish Home.

Part of the problem stems from cost: Before the pandemic, isolation gowns were about 65 cents each. Now, Marco said, they’re $17.

He has asked hospital chains in Southern California to provide elder care homes with more protective gear, citing their centrality in the numbers of infections and deaths.

“‘If you help us now, we’ll reduce your patients in two weeks,’” Marco told hospitals. “But they have not been able to help us.”

At the Jewish Home, a third resident tested positive Friday, the first new case in more than two weeks. Three staff members have also tested positive. Marco said higher staffing ratios than the law requires were put in place before the pandemic, helping his organization avoid some of the challenges other facilities faced.

Because of the explosive spread of the coronavirus, public health officials try to move quickly in responding to a confirmed case. A team from the Pasadena Public Health Department, for example, investigates those individuals and their contacts.

“We look at their living situation, and they may work at multiple facilities and live with people working at other facilities, and we put them in isolation, too,” Goh said. “We are trying to break the chain of transmission.”

The difficulty of keeping a sufficient number of employees on duty around the clock prompted state leaders to relax minimum staffing requirements for care facilities.

Many employees are still calling in sick or going on leave. An employee at Rose Garden Convalescent Center in Pasadena said she stopped showing up for work after she became disillusioned and panicked by her company’s handling of the outbreak.

“First it’s one, and two, and three” cases, she said, “and then everyone has it.”

While she was still clocking in for her shifts, her bosses had not yet informed the employees of any positive test results. Then city health officials confirmed her fears, saying Rose Garden was the site of an outbreak. She was especially concerned when she learned that a certified nurse assistant who had worked closely with an infected patient didn’t go into quarantine and was still on the job.

“That’s why this thing has gotten so big,” she said, “because people aren’t taking proper precautions.”

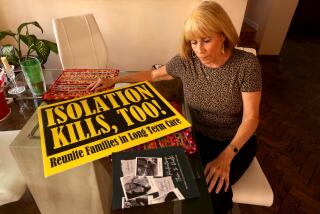

But family members are still barred from visiting their loved ones.

That has been a challenge for Maria DiSarro, who had been seeing her 85-year-old mother daily at the Heights in Burbank, where no cases have been reported.

DiSarro said her mother, a former L.A. County social worker, is in the early stages of dementia. Phone calls can be a logistical ordeal. DiSarro asked the facility if she could have a camera installed in her mother’s room, but administrators balked.

“For me to take my mom out of there and put her in my home would mean I’d have to not work anymore,” DiSarro said. “I can’t have her home alone unsupervised.”

There are some moments of solace for those now isolated. At the Kensington, staffers united last week for a birthday party enabled by a hydraulic lift. Friends and family gathered to celebrate the 91st birthday of Margaret Jones, a real estate investor who has dementia.

Lucy Cavazos, a close friend of 25 years who now manages Jones’ care, stepped onto the lift to be elevated outside Jones’ second-floor room. The two shared greetings through an open window.

“When we sang to her, she was saying thank you, and that she loved us,” Cavazos said. It was a bright spot in a grim month, but she takes it in with a measure of gratitude and a solemn nod to what sometimes feels inevitable.

“I don’t know if tomorrow she’ll know who I am,” Cavazos said.

Times staff writers Kailyn Brown and Rong-Gong Lin II contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.