Focus: Over here: Remembering San Diego’s role 100 years ago in World War I

- Share via

In World War I, the worst loss of American submariners did not occur in contested Atlantic or Mediterranean waters, nor did it involve German torpedoes or depth charges.

Instead, the tragedy was the result of an accident. Four miles off Point Loma, the F-3 collided with a sister submarine, slicing the F-1’s port side like a giant can opener.

“The F-1 sank in 10 seconds,” said Jonathan Casey, archivist and research center manager at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Mo. “Nineteen men were lost and five rescued.”

As a World War I-era song noted, it’s a long way to Tipperary. That’s indisputably true in San Diego, nearly 6,000 miles from the major European battlefields of 1914 to 1918.

Yet when the United States entered the Great War 100 years ago this week, this West Coast port was destined to play a key role. Even before the conflict began, Navy and Army aviators had been honing their skills at Rockwell Field on North Island.

“On April 6, 1917, when the United States entered the war,” Casey said, “Rockwell Field in San Diego was one of only three operating flying fields in the country.”

Rockwell was quickly reinforced, as Washington embarked on a swift and ambitious military expansion.

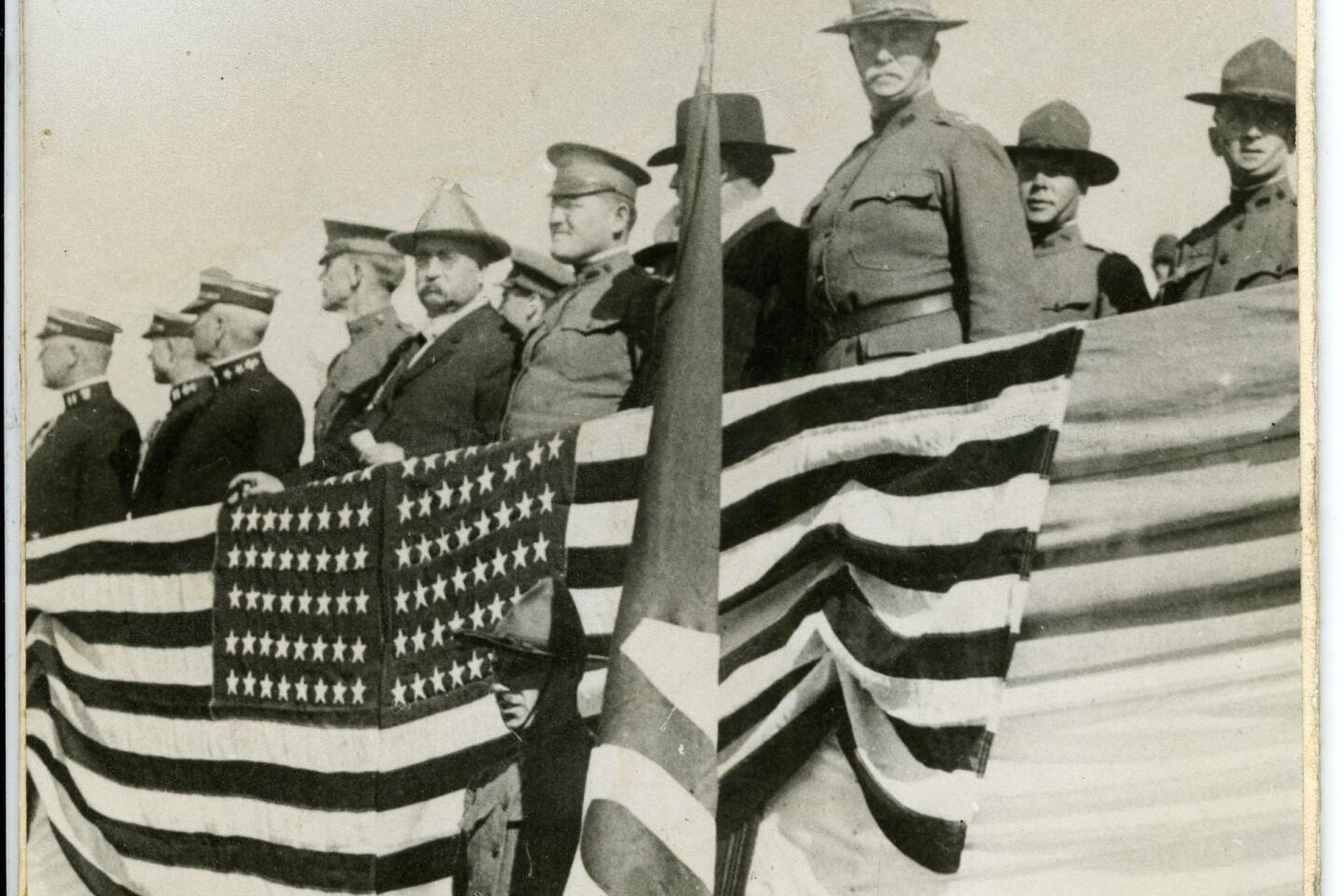

“We went from a standing army and reserve force of about 200,000 to, within a year or so, an army of 4 million,” Casey said. “Training camps were everywhere.”

In San Diego, bases sprang up from Linda Vista to the Mexican border. The largest installation, Camp Kearny, was built to house 32,000 recruits.

Within a year, men who had learned to fly over San Diego Bay would undertake combat missions above France. Soldiers who had drilled in Del Mar would bolster weary Allied troops in the Western Front’s trenches.

In camp and in combat, San Diegans would be among the war’s 116,516 dead and 204,002 wounded Americans. This was a fraction of the war’s total casualties, which are estimated at 38 million. That was small comfort to the Yanks a San Diego High School teacher encountered in field hospitals in France.

“Some were gassed, some shell-shocked,” Georgia Amsden wrote. “MUTILATED IN EVERY CONCEIVABLE WAY.”

The conflict saw murderous innovation — poison gas, tanks, U-boats — and odd experiments. John D. Spreckels, the San Diego industrialist, leased his 226-foot steam yacht to the Navy.

Venetia’s exploits in the Mediterranean were wildly exaggerated by Spreckels, whose claims have been debunked by historians. In contrast, time burnished the record of a North Island-trained unit. The Army’s 135th Aero Squadron destroyed eight enemy aircraft, yet a gunner who logged a single wartime mission may have captured the greatest prize.

In the ruins of a French village, the squadron’s Cpl. Lee Duncan rescued a German shepherd. The dog would soon become a Hollywood legend: Rin Tin Tin.

“The war to end all wars” failed to do so, and later conflicts — World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan — would have more profound impacts on San Diego.

Yet the Great War left its mark on our region and our people.

Virtual city

Early in 1911, more than three years before an archduke’s assassination in Sarajevo precipitated World War I, a military flying school opened on a spit of land jutting into San Diego Bay.

In January 1912, this same location — North Island — became home to the first naval aviation unit. Before year’s end, the Army would establish its own aviation school on the same site.

When Europe lurched into war in August 1914, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed the United States’ neutrality. That policy was soon strained by reports of wartime atrocities and the toll exacted by Germany’s U-boats.

In May 1915, anti-German sentiment soared in the U.S. when a U-boat sank the British liner Lusitania. The ship’s 1,198 dead included 128 Americans.

The president and his allies in the Democratic Party campaigned on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.” Soon after Wilson’s re-election in November 1916, that slogan was no longer true.

On April 1, 1917, as the American cargo ship Aztec entered British waters, it was ripped apart by German torpedoes. As she sank, 28 Americans died.

The next day, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. When the declaration came on April 6, America embarked on a frenzied re-armament campaign.

“When the war started we had one of the smallest standing armies in the world,” said the National World I Museum and Memorial’s Casey. “We were protected by two oceans, we were more or less friendly with Canada and Mexico, although there had been some tensions.

“We were relying on our borders.”

That was no longer enough. By May, naval recruits were marching in Balboa Park, on the grounds of the Panama-California Exposition. In July, construction began on Camp Kearny, a 12,721-acre training camp for the National Guard’s 40th Division. A virtual city occupying a mesa north of Mission Valley, the $4 million installation included more than 800 temporary buildings.

Fort Rosecrans, established in the late 19th century to defend the entrance to San Diego Bay, became the Southern Pacific Coast Artillery District’s headquarters.

The list of local installations was long: Camp Walter R. Taliaferro in Balboa Park; Camp Lawrence J. Hearn near the border; Fort Pio Pico on North Island; the Chollas Heights naval radio station.

On land and at sea, San Diego witnessed nonstop military exercises.

And the occasional catastrophe.

Disaster at sea

The F-1 was a 142-foot-6-inch single-hulled boat, able to voyage 100 nautical miles underwater and 2,300 miles on the surface. Commissioned in 1912, she was a state-of-the-art American submarine.

She was also cursed, or may have seemed so to her crew. In her maiden year, the F-1 came unmoored in Monterey Bay. Tossed by waves, she grounded in the surf. Two men drowned, while 15 escaped.

Worse would follow. On Dec. 17, 1917, both the F-1 and F-3 were cruising on the surface about four miles west of Point Loma. Something went wrong and they collided, hitting with such force that the F-3 tore a 10-foot-long, 3-foot-tall hole in the F-1’s side.

When the F-3 backed out of the F-1, water flooded the wounded sub. The F-1 sank within 10 seconds, taking 19 men with her to the ocean floor, 1,439 feet below the waves.

Four sailors who had been on deck at the time of the accident were thrown clear of the vessel. A fifth, up in the conning tower, dove into the Pacific.

The sole survivors of the F-1, these five men were plucked from the sea by the F-3, the same vessel that had destroyed their boat.

The F-1 was lost at sea, yet it would be found nearly 60 years after it sank. In October 1976, naval oceanographers seeking a crashed F-4 stumbled upon the wreck.

“It looked like a big ax had hit her,” Lt. Dave Magyar, one of the researchers, told reporters.

The ‘Avenger’

After departing San Francisco in the wake of the 1906 earthquake, John D. Spreckels set out to become one of San Diego’s merchant princes. He bought up local landmarks: The Hotel del Coronado. The San Diego Union and The Evening Tribune. The Oceanic Steamship Co.

Anchored in San Diego Bay was another of his prized possessions, the Venetia.

Built in Scotland, the sleek yacht had 10 wood-paneled staterooms, a smoking room, a library, a player piano. Spreckels, who bought her from another tycoon in 1910, cherished his time aboard the steam-powered vessel. He often embarked on cruises, some for only a few days, others for months.

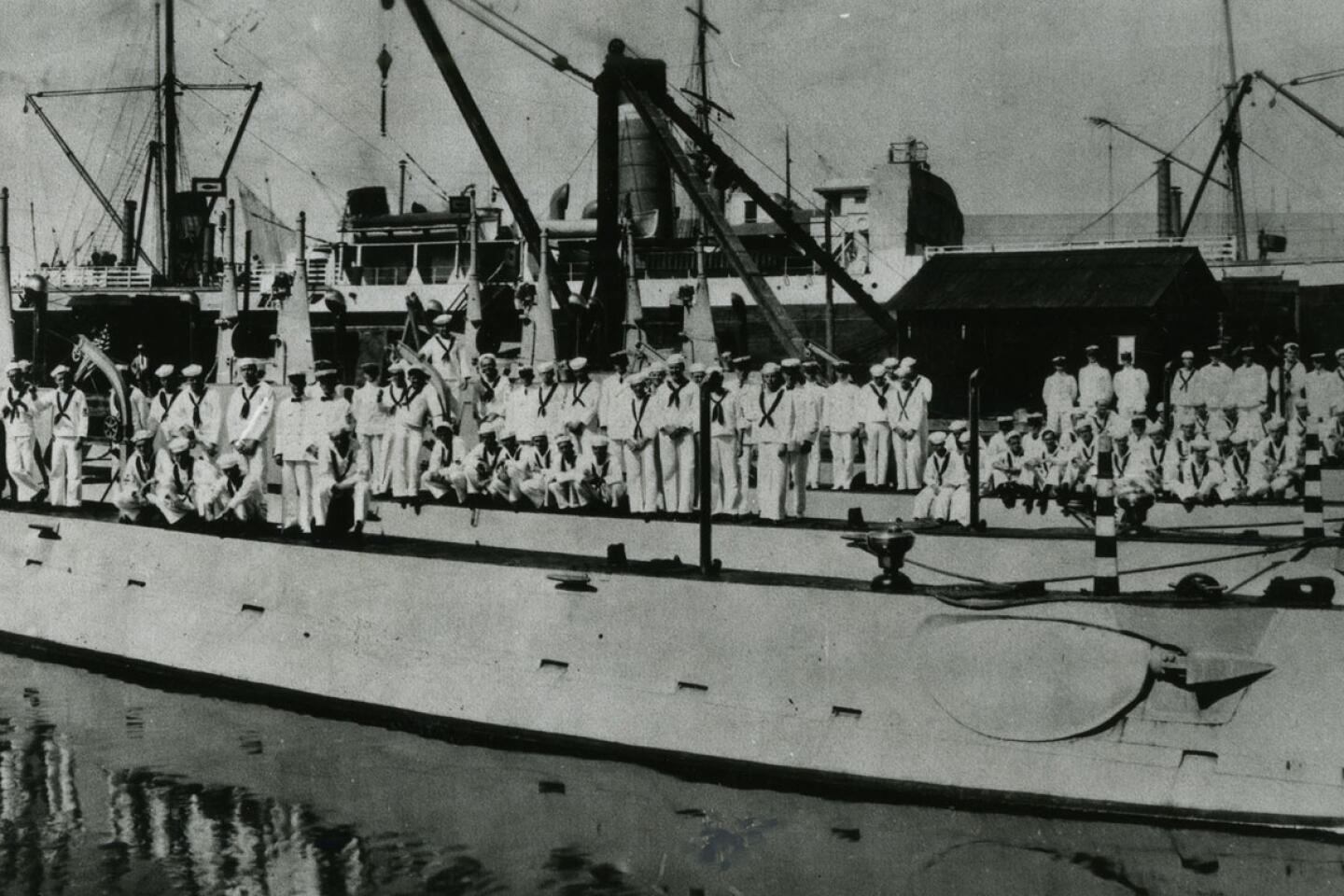

When the U.S. entered the war, though, Spreckels leased his beloved yacht to the Navy. Transformed into a warship — farewell, player piano! — with machine guns and racks full of depth charges, she was dispatched to the Mediterranean.

Her crew of 69 included 22-year-old Ed White, a Kansan who had joined the Navy to see the world.

“They were based in Gibraltar,” said Bill White, 67, who as a boy relished his grandfather’s yarns of life aboard a pleasure craft-turned-warship. “They escorted several convoys and engaged German submarines at least three times.”

“Engaging” meant dropping depth charges in areas where a periscope or surfaced sub had been spotted. Ed White dreaded these moments. As a water tender second class, his battle station was below decks with the Venetia’s boilers.

“When the depth charges detonated, my grandfather was in the engine spaces,” Bill White said. The underwater explosions rocked the Venetia, and Ed White could imagine concussions rupturing the boilers, which would shoot out potentially lethal jets of scalding water.

While Venetia served honorably, historians say it is unclear whether the yacht sank or damaged any submarines. Spreckels, though, had no doubts. After recovering his yacht in April 1919 — along with a $76,000 government check for expenses — the proud magnate commissioned a book.

In heroic detail, “Venetia: Avenger of the Lusitania” described the yacht’s destruction of the U-20, the German boat credited with torpedoing the British ocean liner.

A good story but not, alas, a true one.

“The U-20 actually ran aground in the North Sea,” Bill White said. “In 1916.”

Like the U-20, Ed White and the Venetia are gone. The ship was scrapped in 1968; her crew member outlived her by one year.

White left the Navy and returned to his native Kansas, where he enjoyed visiting the World War I museum. With his grandson at his side, he’d point out one of the smaller displays, a plaque that had been liberated from the Venetia.

A certain water tender second class had pried it off one of the yacht’s pumps — pumps that, despite depth charges, had held fast.

From hell to ‘Hell’s River’

Like other units from San Diego, the 135th Aero Squadron took a long, meandering journey to the front lines.

Comprised largely of Southern Californians, the men of the 135th spent almost four months training at North Island’s Rockwell Field.

Then they boarded a train to New York.

A ship to Scotland.

A train to England.

A ship to Le Havre, France.

Then railway cars to several air bases scattered across the French countryside.

On Aug. 7, 1918 — a year and six days after first assembling on North Island — the 135th logged its initial wartime sortie. In the war’s last three months, the unit completed 1,016 missions, shot down eight enemy aircraft and lost five men in action.

When the 135th returned to the States in June 1919, it could not boast a famous ace like the “Hat-in-the-Ring” squadron’s Eddie Rickenbacker. But Cpl. Lee Duncan brought home a German shepherd who was destined to become an international celebrity.

Duncan discovered Rin Tin Tin in Fluiry, a French village occupied by the Germans and then recaptured by the Allies. Entering the town on Sept. 15, the corporal found that most of the buildings had been shredded by artillery and gunfire.

The ruins included a kennel filled with torn, dismembered dogs. In this hellish scene, though, were six survivors — a German shepherd nursing five puppies.

Duncan, whose childhood had included years on a ranch near San Diego, rescued the dogs. He found homes for the mother and three of the puppies, keeping a young male and female for himself.

He brought the puppies home to Southern California, where a new industry was capturing the attention of a war-weary population. In 1922, Rin Tin Tin made his screen debut in the movie “The Man From Hell’s River.”

“Hell’s River” was a hit, thanks in part to the charisma of “Rinty.” In about two dozen films and serials, the dog enjoyed top billing over his human co-stars.

“There had been movie dogs before him,” said Charles Meeds, a San Diego fan of early Hollywood. “But he made a whole slew of feature-length movies in the 1920s.”

Rin Tin Tin’s acting range dazzled critics. His poses and mobile face expressed concern and determination, ferocity and devotion. “Rin-Tin-Tin is extraordinarily sagacious,” The New York Times’ reviewer wrote of his performance in “The Hills of Kentucky.”

“Hills” was one of the dog’s four starring roles in 1927. In her 2011 biography, “Rin Tin Tin,” Susan Orlean reports that the German shepherd’s performances that year initially won the most votes for a new award: the “Best Actor” Oscar.

“But members of the Academy,” Orlean wrote, “anxious to establish the new awards as serious and important, decided that giving an Oscar to a dog did not serve that end...”

In the end, the Oscar went to Emil Jannings, the German-born star of “The Last Command” and “The Way of All Flesh.”

Generations of German shepherds — some of them direct descendants of Rinty, others not — kept the Rin Tin Tin brand alive in movies and TV shows into the 1990s. The original dog died in 1932; Duncan died in 1960 in Riverside.

Man and dog, they were followed into eternity by a long parade of fellow World War I veterans. The last, Florence Green, a veteran of Britain’s Royal Air Force, died on Feb. 4, 2012. She was 110.

San Diego has been without a living World War I veteran since April 15, 2005, with the death of Julio “Jay” Ereneta. A Filipino native who had served with the Navy, clearing mines from Scottish and Norwegian ports, Ereneta lived to the age of 103.

Local men and women who served in the Great War as sailors and airmen, doughboys and nurses, mechanics and ambulance drivers — they’re all gone now. All that’s left are some of the bases where they trained, relics they touched and stories they passed on to posterity.

Staff researcher Merrie Monteagudo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.