A Win for Texas Western, a Triumph for Equality

- Share via

WASHINGTON — A lot of people now claim to have been there on March 19, 1966. Forty years later, with Kentucky vs. Texas Western having become the most significant game in college basketball history, a whole lot of folks who weren’t inside Cole Field House say they were. It wasn’t a happening at the time, even though the NCAA championship was at stake. Only in retrospect, through some fairly intense examination, have we come to know it was the night that basketball changed forever.

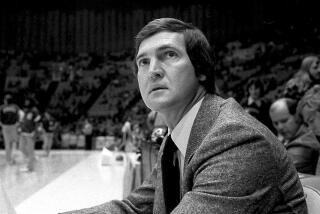

Gary Williams actually was there. He was a sophomore at Maryland, a guard on the Terrapins basketball team he would later come to coach. He didn’t have a ticket to the game, didn’t have any business inside the gym. “I snuck in,” he said Thursday night. “I was curious about Texas Western mostly because they had guys from New York City and I grew up in southern Jersey....Remember, nobody east of the Mississippi had any idea of what Texas Western looked like. There was no TV then where you could see them. OK, there was one ACC game a week, on Saturdays at 1 in the afternoon. That was it. And that was only televised from Washington to South Carolina.”

So Williams sneaked in the back door at Cole with a couple of teammates, one of whom was Billy Jones Jr., the first black basketball player at Maryland, and the first in the Atlantic Coast Conference. They didn’t know they were about to see something historic. They didn’t even know there had never been an all-black team in the Final Four, or that Adolph Rupp had taken exception to his all-white Kentucky team having to share the floor with these black boys from Texas Western, now Texas-El Paso. They certainly couldn’t have dreamt that the circumstances, the culture of the times, and most importantly the outcome would conspire to create enough buzz over 40 years that the evening would turn into a movie, “Glory Road.”

Though the usual cinematic license has been taken -- trust me, there were no 180-degree dunks in NCAA games in 1966. In fact, throwing it down was called a “stuff shot” then, not a dunk, and even Wilt didn’t really dunk -- the movie does take you on a journey with the 1966 Texas Western team that was integrated but whose coach dared start five black players for most of the season, a fact that brought out the ugly in a lot of people who thought blacks were too dumb to excel in basketball, and let the Miners know it.

But Williams, Jones and whoever else sneaked in with them didn’t go searching for a cultural awakening. “In fact, when I came to Maryland,” Williams said, “I didn’t know Maryland and the ACC were all-white. I grew up in southern Jersey. I had always played against black kids. The thing there was you went looking for the best games. We’d go to play against Walt Hazzard and some of the guys in Overbrook [who were black] and the black players would wind up coming to play games in white suburbs. But we did notice that Texas Western’s starters all were black. We teased Billy Jones about it.”

There were so many stereotypical notions about black ballplayers then, particularly the farther south you got. Mostly, it was presumed they were undisciplined and stupid. “We all just assumed,” Williams said, “that Texas Western would throw behind-the-back passes and shoot the ball from 25 feet. And people didn’t know, of course, that the Texas Western Coach, Don Haskins, had played for Hank Iba and nobody who ever played for Coach Iba would run a team that way. And when the game got started, we all sat there and watched Texas Western run a better half-court offense than Kentucky, and play better man-to-man defense than Kentucky. There were possessions where Texas Western passed it 10 times before taking a shot. It was beautiful.”

There’s no reason for anybody who considers himself a basketball fan not to know the real story of that game or the outcome. That Texas Western team featuring Bobby Joe Hill, David “Big Daddy D” Lattin, Nevil Shed and Harry Flournoy beat Rupp’s Kentucky team featuring Pat Riley -- yes, that Pat Riley -- and Louie Dampier, 72-65. This was before the UCLA run of seven straight championships, remember. Kentucky was college basketball royalty, the leader in the pack with four national championships, and as white as milk. No, black players weren’t new to the game. As my friend Ron Rapoport writes in the Chicago Sun-Times, in 1962, the University of Cincinnati won the NCAA championship with four black players. In 1963, Loyola of Chicago won the title with four black players. And by 1966, the four best players in the NBA, unarguably, were Wilt, Bill Russell, Oscar Robertson and Elgin Baylor.

But they weren’t playing for a little school in south Texas. They weren’t riding the coattails of one white player. And they didn’t have to play a championship game in an ACC gymnasium against Rupp, who fairly or not, was the face of segregated college teams in the south, along with Bear Bryant. It’s hard even now for a whole lot of black folks to root for Kentucky, even though a black man, Tubby Smith, is the head coach. And of course, the great irony here is that Riley might just be the most popular white man in black world. Riley has embraced the significance of that night and embraced the Miners to the point that they’ve invited him to their team’s reunions.

The hatred those Texas Western players endured, nasty as it was, ultimately produced a journey and an ending that Disney felt compelled to make its own. And that larger story of triumph is what has so profoundly affected people who really were there that night, people like the current men’s basketball coach at Maryland.

“The Southeastern Conference was holding out [against integration],” Williams said, “but once they got their butts whipped that night it forced their hand. And the ACC was probably waiting on us [to integrate] because we were the northern-most school in the league....

“But as a coach especially, I so appreciate having been there. I have more appreciation for what the game means, for the people who would go through so much to play it. I think back on how even the people who taught the game thought that black players weren’t smart enough to play the game well. Every coach I had when I was young would say, ‘Now listen, you’re playing against a black player tonight. You’ve got to pump-fake him because he’ll automatically jump in the air and foul you.’ But that night, watching the way Texas Western played, if you had stereotypes in your head about basketball and you were in Cole, it changed the way you thought, changed the way you felt. It’s very seldom that one event, that something which took less than two hours, could affect people so dramatically.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.